2024 marks the 20-year anniversary of the Boston Red Sox team that lifted the curse of all curses over the city of Boston. For BostonMan writer Nate Graziano and two generations before him, it was a lifetime coming.

A BLOOD MOON hung in the night sky above Busch Memorial Stadium in St. Louis on October 27, 2004, a night that ended 86 years of abject misery for the Boston Red Sox and their devoted fanbase.

A blood moon—a name that describes the Earth’s moon during a total lunar eclipse—hung in the night sky as Edgar Renteria dribbled a ground ball back to Red Sox closer Keith Foulke, who tossed it underhand to first baseman Doug Mientkiewicz for the final out of the 2004 World Series.

It would turn out to be the first of four World Series titles that the Red Sox would go on to win in the new century. It was the first championship since 1918 when the Red Sox owner traded their star player to the New York Yankees so he could produce a play.

There was a blood moon in the sky that night when I woke my daughter, Paige, in her crib and carried her downstairs to watch the final out with me. My wife was pregnant with our son and fell asleep early, and I needed someone to share the moment with me.

But it wasn’t without trepidation that I woke my daughter. You see, in 1986, my father woke me to watch the Red Sox win the World Series.

I was eleven years old, in the sixth grade, enjoying a deep sleep, as Game 6 between the Red Sox and the New York Mets stretched into the tenth inning. A cautious and circumspect man, my father waited until the last possible minute before waking me.

With two outs and a two-run lead—Red Sox pitcher Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd had allegedly already cracked the first bottle of champagne in the locker room—my father nudged me in my bed. “Get up,” he said. “The Red Sox are about to win the World Series.”

Elated, I followed my father into his bedroom where he was watching the game on an old television set. My mother worked third-shift as a nurse, and my younger sister was still asleep, in different to the fate of the Red Sox. It was the type of father/son bonding moment that couldn’t have been scripted any better.

Until the wheels fell off the wagon. Most New Englanders of a certain age know how that night ended.

When Mookie Wilson hit a slow ground ball down the first base line, and the ball went through a hobbled Bill Buckner’s legs, my father lost his proverbial shit—as I would lose my proverbial shit 17 years later after Game 7 of the 2003 ALCS when the Red Sox would lose to the Yankees after an eleventh inning walk-o home run that convinced me that curses were real.

There wasn’t a blood moon in the sky on either of those nights in 1986 and 2003, respectively.

There was a blood moon in the sky as I cried on the night of October 27, 2004.

I cried for the end of 86 years of torment and unanswered prayers and “you’ll get ‘em next year.” I cried for an entire generation of fans who lived long lives and died without ever seeing the Red Sox win a World Series. I cried for my daughter, who was asleep in my arms, and my son, who was unborn.

I cried for every blood moon that I had ever seen before, and every blood moon that I would ever see again.

I cried then I called my father.

He answered the phone on the first ring. “They did it,” my father said. On the television set in the background, the 2004 Red Sox—the self-proclaimed “Idiots”—continued to pig-pile on the St. Louis pitchers’ mound.

“I know,” I said and didn’t know what else to say, afraid I might cry again. Of course, there was so much I wanted to say in that moment about the things I didn’t realize that I had just learned about hope and faith.

And blood moons.

We hung up without another word spoken, and I put my daughter back in her crib and climbed in bed beside my wife and fell asleep. I awoke in a new world where—sometimes—just believing can be enough.

CURSES, CURSES, CURSES

TO believe in the curse, the hex or the jinx is to defy the logical world and accept the supernatural realm as reality. Most certainly, some things happen in life that confound explanations, things that are dicult to dismiss as a mere coincidence.

And sometimes bad things happen at such a regular clip, or in such close proximity to each other, that one might be inclined to call it “a curse,” or some other irrational label.

In the case of the Boston Red Sox, an organization so wildly snake-bitten for 86 years—with such a preponderance of misfortune—the facts could lead even the staunchest cynic to call it “a curse.”

I’m talking, of course, about “The Curse of the Bambino.”

Most Red Sox know the general story, but some details might be murky.

The first World Series was played in 1903 and won by the Boston Americans, who would change their name to the Red Sox in 1908.

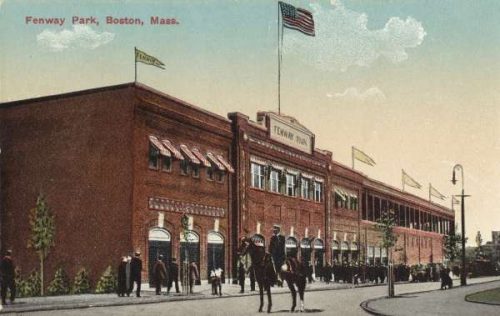

In 1912, Fenway Park opened—days after the RMS Titanic hit an iceberg and sank in the North Atlantic Ocean—and in the inaugural season, the Boston Red Sox defeated the New York Giants and won a second World Series.

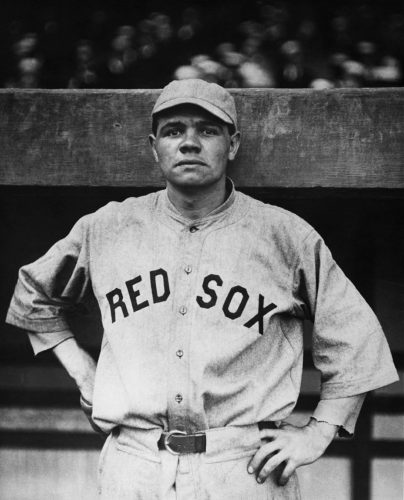

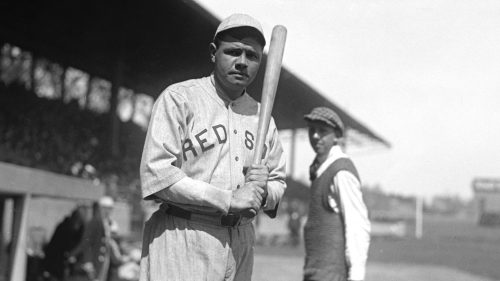

In 1914, a once-in-lifetime phenom named George Herman “Babe” Ruth—nicknamed “The Bambino”—came to Boston. Ruth was a star pitcher, as well as a slugger, and with Babe Ruth, the Red Sox won three World Series in 1915, 1916 and 1918.

In the 1918 World Series, Ruth was the winning pitcher in two of the six games against the Chicago Cubs.

After the season, Ruth demanded an increase in his salary from the team owner and theater producer, a guy named Harry Frazee. Frazee signed Ruth to a three-year $27,000 contract.

Ruth—a notoriously free-spirited guy—reported late to spring training in 1919, and the Red Sox went on to finish in sixth place that season, despite their highly-paid superstar. Still, after the inglorious finish, Ruth again wanted to renegotiate his contract with Frazee, who was in debt and trying to produce a play called “No, No Nanette.”

So on December 26, 1919, Frazee sold Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees—where he was assigned the Number “3”—a franchise that had yet to win a World Series; meanwhile, the Red Sox had already won five titles.

It would be another 86 years until a blood moon, a bloody baseball, a bloody sock and the “Idiots” would end the “Curse of the Bambino.”

NO MAS

THE BOSTON GLOBE writer and editor Marty Nolan famously penned the line: “The Red Sox killed my father, and they’re coming after me.”

Nolan wrote this line a year after his father had passed away, having never witnessed his team win a World Series. Then Nolan—and the rest of New England—had to watch Mookie Wilson’s slow ground ball dribble through Bill Buckner’s five-hole, completing one of the biggest chokes in sports’ history.

Talk about a slow death.

Between the years of 1919 and 2003, the Boston Red Sox only appeared in four World Series, after winning five of the first 15. In each of the four appearances, the Red Sox went to a Game 7, and in each of the four appearances, the Red Sox lost in Game 7.

Was this a curse? Could you still call this a coincidence?

In 1946, the Red Sox made their first World Series since beating the Cubs in 1918, playing against the St. Louis Cardinals. The line-up that year featured the three legends that the late-David Halberstam would prole in his brilliant 2003 book “The Teammates”—inelders Johnny Pesky and Bobby Doerr, and “The Splendid Splinter,” left elder Ted Williams.

The Red Sox lost that series after Pesky, allegedly, double-clutched a relay throw during a tie game in the eighth inning of Game 7.

After two dismal decades of baseball in New England, the 1967 “Impossible Dream” team brought the game back to life in Beantown. Aside from Carl Yastrzmeski—who won the Triple-Crown that season—there were few superstars on the roster and no real expectations for a team that went on to win the American League pennant on the last game of the regular season.

The Red Sox would again face o with the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series that year, and again it would go seven games. But this time Boston would meet up with a buzzsaw named Bob Gibson, who threw a complete game—and hit a home run to help his own cause—in Game 7 and dashed the 1967 Red Sox hopes of a fairytale ending.

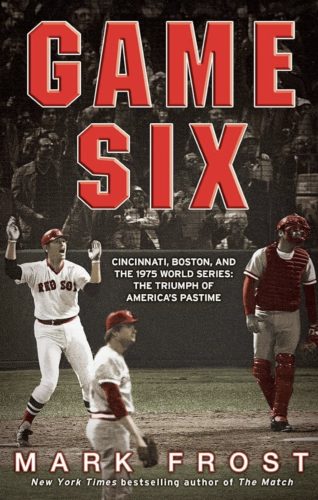

The 1975 Boston Red Sox had an air for the dramatic, again making it to the World Series. This time the Red Sox faced o with the Cincinnati Reds.

During Game 6, which some baseball people will still label one of the greatest games ever played, Red Sox catcher and New Hampshire-native Carlton Fisk hit his iconic walk-off home run over the Green Monster, wishfully guiding the ball into fair territory with his arms.

Ahead by three runs—Ruth’s number again—in Game 7, the Red Sox squandered the lead and lost the World Series.

Things only got worse from there. Enter New York City.

In 1978, the Red Sox were up 14 games on the Yankees on July 19 when the wheels started to come o the wagon. They had a four-game lead over New York entering a four-game series against the Yankees at the end of the regular season.

The Yankees swept them at Fenway in what some fans still refer to as “The Boston Massacre,” and at the end of the regular season, the teams were tied for first place, forcing a one-game playoff at Fenway Park.

Three words: Bucky Fucking Dent.

Then, in 1986, the Red Sox seemed to be a team of destiny with a young Roger Clemens setting the major league record for strikeouts in a single game in April and going on to win the AL Cy Young

Award. In the ALCS against the California Angels, the Red Sox would come back from a 3-1 deficit, bolstered by Dave Henderson’s two-run dinger with two outs in the ninth inning of Game 5, an elimination game.

The suddenly-lucky Red Sox were on to another World Series against the New York Mets.

Then the alleged “Curse of the Bambino” really bit them in the ass in Game 6, arguably the most brutal loss in franchise history. In Game 7, the Red Sox, again, surrendered a three-run lead, losing the series.

Is it worth noting, again, that Babe Ruth wore the number “3”?

ENTER THE EVIL EMPIRE

WHEN Frazee sold Ruth to the New York Yankees for $125,000 and $300,000 loan, which he used to pay the mortgage on Fenway Park and produce “No, No Nanette,” it also seemed the two franchises had traded identities.

As noted, from 1903 to 1918, the Red Sox won five of the first 15 World Series titles while the Yankees were blanked. After the sale of The Bambino, the Bronx Bombers went on to win a jaw-dropping 26 World Series rings between 1919 and 2000.

Meanwhile, the woe-begotten Red Sox did not win a single title.

As baseball entered the 21st Century, the rivalry between the two East Coast cities had reached a fevered pitch.

By 2003, when the Red Sox squared o against the Yankees in ALCS, the two teams had formed the greatest rivalry in professional sports, and one thing was abundantly clear: Neither the players nor the fanbases liked each other.

The series went to Game 7 at the old Yankee Stadium in the Bronx, and the Red Sox had secured—surprise, surprise—a three-run lead going into the bottom of the eighth inning with their ace Pedro Martinez throwing a gem.

Then the wheels fell off the wagon. Manager Grady Little sealed his ticket out of town by keeping an exhausted Martinez on the mound when any casual baseball fan knew it was time to take him out.

The Yankees tied the game, and in the bottom of the 11th inning, Aaron Fucking Boone took a Tim Wakeeld knuckle ball over the left eld porch and drove yet-another dagger through the hearts of Red Sox fans.

“The Curse of the Bambino” had struck again and again, it was at the hands of the team that the late-GM Larry Lucchino had labeled “The Evil Empire.”

That night I remained in a catatonic state until 3 a.m., sitting in a rocking chair and staring at a white wall.

The next morning, I wrote an editorial for The Hippo Press in Manchester, N.H. titled “A Red Sox Fan Explains,” which appeared in Oct. 23-29, 2003 edition of the weekly newspaper.

Maybe I captured what some Red Sox fans were feeling at the time with this excerpt from the piece:

Here me out. I’m heartbroken.

“Get over it, guy. They’re just a baseball team,” you might be inclined to say. And you very well might be right. But this is a team that I watched each night from April to October with a religious fervor. This is a team that I think about in the majority of my idle hours. Again, why?

There’s something about the utter meaningless of baseball that I find cathartic. I’m not someone who has an easy time showing affection. But I allow myself to be devoted and passionate about a game that doesn’t mean anything in the global scheme of things. It’s refreshing for me. And when I offer all of this devotion and come up with the short end of the stick, again…

We’re back to the broken heart.

Sure. “We’ll get ‘em next year.” But offering up that sentiment simply isn’t going to cut it this time. I’m hurt. And can anyone other than a Red Sox fan possibly understand what we’re going through in these dismal days following what will be remembered as one of the most devastating nights in Boston baseball history?

Little did I know that the Red Sox would, indeed, “get ‘em next year” in one of the most dramatic series in the history of professional sports.

A BLOODY BASEBALL, A BLOODY SOCK AND A BLOOD MOON

BLOOD, as a sacred life force, is rife with symbolism. In many ancient religions, blood—in the form of a human or animal’s death—was offered as a sacrifice to a deity, sometimes as a form of redemption or atonement.

In Christianity, God sacrificed the blood of his only son so that mankind’s sins would be forgiven.

For Red Sox fans, blood was essential in breaking “The Curse of the Bambino,” so Frazee’s terrible sin could finally be forgiven by the baseball gods.

In August of 2004, the Red Sox started to surge, following a July that saw Red Sox catcher Jason Veritek feed the Yankees third baseman, the contemptible Alex Rodriguez a faceful of catcher’s mitt, then Red Sox third baseman Bill Mueller won that same game with a walk-o home run o Hall-of-Fame closer Mariano Rivera.

The next week, the Red Sox surly shortstop Nomar Garciaparra—once the face of the franchise—was shipped to the Chicago Cubs at the trading deadline and replaced by Orlando Cabrera.

On the night August 31, 2004—when there was a full moon—a 16-year-old Sudbury boy named Lee Gavin attended a game at Fenway Park where the Red Sox were playing the Anaheim Angels.

Gavin was sitting in right eld, near the Pesky Pole, when slugger Manny Ramirez seared a foul ball down the right eld line. Gavin went to catch the ball, but it slipped through his hands and hit him in the face, cutting his mouth and knocking out his two front teeth.

Gavin was hauled o in an ambulance, and the Red Sox organization made arrangements to have Ramirez sign the bloody baseball for the teenager.

But supernatural forces may have been at play. The Red Sox went on to beat the Angels 10-7, and that same night, the Yankees suffered their worst defeat in franchise history, taking 22-0 ass-kicking from the Cleveland Indians (now Guardians).

Additionally, it turned out that Gavin lived with his parents in a farmhouse in Sudbury that was once owned by the Bambino himself.

“I’m not sure I would say something supernatural was at work, but there were several coincidences that occurred in 2004 that lined up nicely to make you think about it,” Gavin told reporters at the time.

The Red Sox never caught the Yankees, who won the AL East by three games over the Red Sox, but Boston managed to procure the single Wild Card spot.

The Red Sox swept Anaheim in the ALDS and the Yankees defeated the Minnesota Twins, setting the stage for a repeat of the previous season’s ALCS.

And it didn’t start well for the Red Sox. They dropped the rst three games, and no team in major league history had ever come back from a 0-3 deficit to win a postseason series.

Yet “The Idiots” remained optimistic. “Don’t let us win today,” first baseman Kevin Millar famously said to Boston Globe columnist Dan Shaughnessy. “We have Pedey [Pedro Martinez] tomorrow, and we have Schill [Curt Schilling] Game 6, and Game 7, anything can happen.”

Then after two improbable wins with David Ortiz walk-offs in Games 4 and 5, the series shifted back to the Bronx for Game 6, where a blood sacrifice would, once again, factor into the equation.

The story of “The Bloody Sock” game starts in the ALDS when Curt Schilling tore the tendon sheath on his right ankle pitching against Anaheim. Schilling started Game 1 of the ALCS and was miserable, clearly injured. It was unknown if Schilling would be available to return in a Game 6, if the series went that far.

Schilling and team doctors decided to give it go, and the team doctors performed a barbaric surgery in the locker room before the game to suture the torn tendon in place. While bleeding from the ankle, soaking his sock in blood, Schilling pitched seven stellar innings, allowing only one run and leading the Red Sox to victory and forcing a Game 7.

Despite the persistent chants of “1918” from the fans at Yankee Stadium, the momentum in the series seemed to have palpably shifted after Schilling’s gutsy and bloody performance in Game 6.

After centerelder Johnny Damon smashed a grand slam into the right eld seats in the second inning, Game 7 was never really close, but even with a seven-run lead entering the bottom of the ninth, Red Sox fans watched with bated breath, waiting for the wheels to fall o the wagon…again.

So when Rueben Sierra hit an Allen Embree pitch weakly to Pokey Reese at second base, who tossed it to Doug Mientkiewicz for the final out, Red Sox fans breathed an 86-year sigh of relief. Even if the Red Sox had lost in the World Series, at that point, it still felt as if “The Curse of the Bambino” had been exorcized.

And the World Series, against the St. Louis—who had defeated the Red Sox in seven games in 1946 and 1967—felt like a foregone conclusion. It was never close.

A blood moon hung in the St. Louis night sky as Edgar Renteria dribbled a ground ball back to Red Sox closer Keith Foulke, who tossed it underhand to rst baseman Doug Mientkiewicz for the nal out of the World Series.

On his back, Renteria wore the number “3” as I fell to my knees in front of the television set in my living room and cried. “The Curse of Bambino” was offcially lifted.