He’s one of the greatest Red Sox outfielders of all time, boasting a 20-season MLB career filled with accolades to makeup a HOF worthy resume. Dwight Evans biggest challenge -and achievement- however is his on-going fight to bring awareness and one day a cure for neurofibromatosis (NF), a condition that sadly claimed the lives of his two sons.

IT’S interesting how -and the way- history remembers things. Especially in sports.

As I get older, and hear newer generations talk about the athletes I grew up watching, some moments and some players are glorified in ways that -to me at least- seem a bit of a stretch beyond what I remember.

Others, meanwhile, seem to not be completely remembered for how freaking good they actually were.

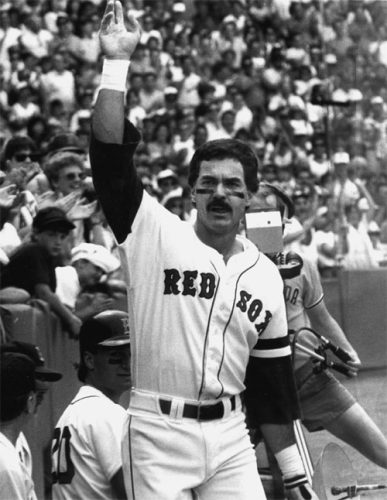

For nineteen summers, from 1972 through 1990, Dwight Evans patrolled the outfield grass at Fenway Park for the Boston Red Sox, winning eight Gold Gloves during that time.

History remembers ‘Dewey’ as an elite and gifted outfielder -deservedly so- and he can be found on many ‘Greatest Defensive Outfield’ lists at sports bars everywhere throughout Boston.

But many, even those that watched him night and night out all of those years, need to sometimes be reminded how good Dwight Evans was at the plate as well.

Who remembers in 1981 that he led the American League in home runs? Who remembers that throughout the 1980’s he led all of major league baseball in extra base hits? Who remembers that three times Dewey led the majors in bases on balls? And twice led in OPS? Who remembers that he also once led in runs scored for a season? And also once led in total bases? Who remembers Dewey as a two-time American League silver slugger recipient? And three time all-star?

The list goes on. Whether or not we remember all of these baseball accolades or not, there is something about Dwight Evans that almost none of us -even his closest teammates and coaches- ever knew.

Throughout his playing career, every day Dwight Evans suited up for a game, he was doing so while his wife Susan and he were caring for their two sons, Justin and Timothy, who were courageously battling neurofibromatosis (NF) at home.

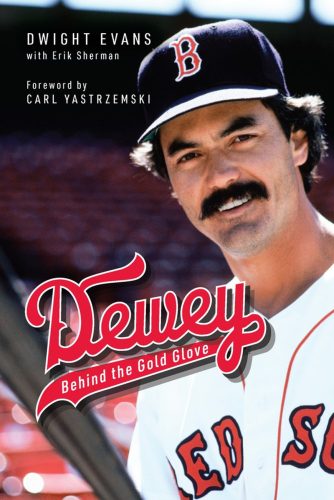

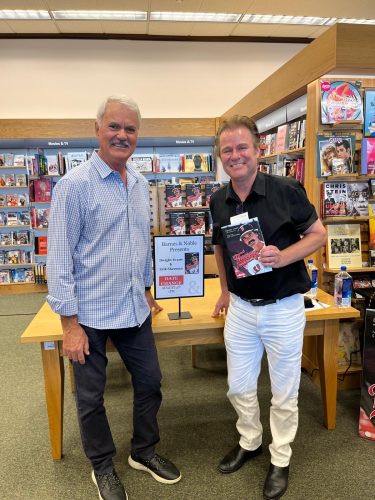

Last summer (July 2024) with acclaimed author Erik Sherman, Dwight Evans released his autobiography DEWEY, Behind the Gold Glove, in which he opens up publicly about many things for the first time in his playing career, and more significantly about the daily battle Justin and Timothy waged their entire life -and throughout Evans playing days- fighting NF, a devastating genetic disorder of the nervous system, before both passing away within ten months of each other in April 2019 and February 2020 respectively. The books has been universally hailed as one of the most important sports books this century and was a finalist in 2024 for the prestigious Casey Award, given annually to the best baseball book of that year.

The following is an excerpt from DEWEY, Behind the Gold Glove, Chapter 1, A Private Matter. All in the words of Dwight Evans and Erik Sherman.

CHAPTER 1 – A PRIVATE MATTER

JIMMY Rice never knew. The teammate and friend with whom I shared the Fenway Park outfield for sixteen seasons never knew how neurofibromatosis (NF), a genetic disorder of the nervous system that causes tumors to grow on nerves, had devastated the lives of two of my sons, Timothy and Justin, throughout most of my Red Sox career and beyond.

But Jimmy’s unawareness of their severe condition would change on an early July evening in 2006 up in a Legends Suite at Fenway Park, where Rice and I were hosting a group of twenty-five fans as team ambassadors for the Red Sox.

Earlier in the day, Jimmy and I had attended the 20th annual NF Golf Tournament at the International in Bolton, MA. My wife, Susan, and I had just been named honorary chairs of the event that year, and Jimmy read a bio about my family and the immense challenges we had endured for more than three decades in a pamphlet distributed at the tournament.

Upon learning further details of our struggles from me at the suite, one of the most physically imposing men in baseball history became overwhelmed with emotion.

“Dewey! Dewey! I never knew! I never knew!” he kept repeating as tears welled up in his eyes. “I just never knew this was going on with your kids. I had no clue!”

That reaction from a big, strong guy like Jimmy Rice kind of took me back. I was really touched by his sensitivity and concern.

It would be natural to wonder how a teammate of mine for all of those years could have been so uninformed about my sons’ serious malady. But the fact is, it was entirely my doing.

None of my teammates, except for my closest friend, confidante, and mentor in baseball, Carl Yastrzemski -who suffered the pain of losing his own son, Michael, twenty years ago- really knew any of the details or the severity of the situation.

In baseball, you talk about the game, you talk about the weather. Nobody wants to hear about your problems. You just don’t share all that much about your family life.

Freddie Lynn, who manned centerfield so magnificently for us in Boston for seven seasons, would say how he and some our teammates knew my boys were not well -the disfiguring effects of the disease were very evident -but they didn’t know specifically the term for what they had or the extent for how serious it was. They also didn’t want to intrude so they respected our privacy.

Bill Lee, our masterful left-handed pitcher for so many years, would say he felt a sense of helplessness; the typically loquacious ‘Spaceman’ simply didn’t know what to say to me. And I get it. It’s the kind of thing where you’re not sure what to ask and what to ask about.

Neurofibromatosis is a word a lot of people can’t even pronounce. And when you’ve got thirty or so guys in the clubhouse -not counting coaches, players on the disabled list, and clubhouse workers- there’s a lot going on.

It’s all business in there. So it was never discussed, even when Susan and I would bring the boys and our daughter, Kristin, to the Red Sox clubhouse. On such occasions, we acted as if nothing was wrong, and the boys behaved like happy and healthy and kids.

Susan and I didn’t do anything other than just love them and try to treat them as normally as possible. One thing you didn’t want to do was make them feel sorry for themselves.

As for me, I never made any excuses about how my lack of sleep and worrying about my family may have affected my play on the field. There were many nights I was at Fenway Park after having come straight from the hospital following one of my boys’ many surgeries and wasn’t having a good game.

And you know what? I just had to eat it. I had to eat it from the press. And I even had to eat it from the fans.

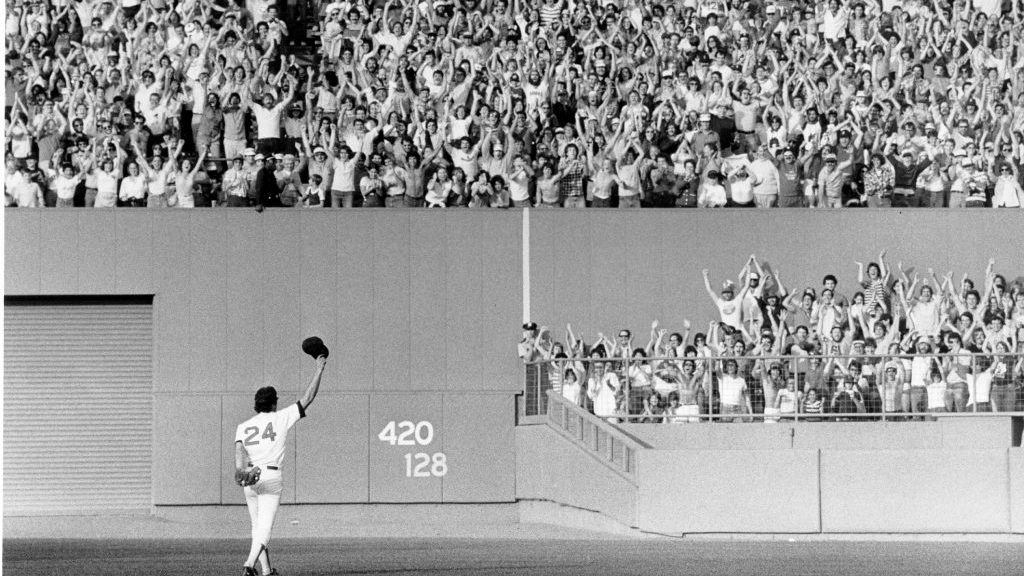

But the thing that I did find out after nineteen seasons playing in Boston was how passionate New England fans are. If you’re playing poorly, they are going to boo you. If you make a great play, they’re jumping up and down screaming, and cheering you on.

It’s not that they’re fickle -they’re just emotional. And I love that about them.

I remember my former Red Sox teammate Rick ‘the Rooster’ Burleson telling me after we traded him to the Angels, “I miss New England fans because, in Anaheim, if I dive and make a great play in the hole at short, you’ve got twenty thousand people just saying ‘Wow.’ But in Boston the reaction would be just off the charts after a play like that.”

What’s sad is I see some players who come to the Red Sox who either just don’t get that or don’t have the makeup to play in Boston. It can be a tough place to play, but once you’ve been accepted by Red Sox fans, you’re accepted for life.

The ballpark would become like a sanctuary for me. Once I drove into that Fenway parking lot, it was like a free zone where I could leave everything else behind. And the longer I played, the more it became a refuge where I could release my anxieties and stress for a few hours.

But once I left the ballpark, there ‘it’ was again -that thing that would jump on me when I would often stop by the hospital and stay there as long as I could -then go home and try to grab a little sleep before coming back out the next day and doing it all over again.

In the early years after the diagnosis of both of my sons, I didn’t handle things as well as I did later on. I probably ‘wore it’ too much on the outside.

They always say public speakers are ten times more nervous on the inside than they appear on the outside. That’s not what I was like early on. I couldn’t easily contain my feelings, and it affected my play.

Certain people would say things about my performance, but they didn’t know what I was going through at home. I don’t know how they would have handled it if they knew, but thankfully I played long enough where I could eventually rise above the criticisms and excel at a high level for many years in the big leagues.

After nearly two decades playing with the Red Sox -a period that included winning eight Gold Gloves, leading the American League in home runs and all of baseball in extra-base hits during the 80’s, and being a part of two pennant-winning teams -then another twenty-four years in the organization after my career ended, Boston is as big a part of me as anything else in my life.

I’ve come a long way since the days of walking barefoot wearing shorts and a tee-shirt to Kailua Elementary School in Hawaii.

DEWEY, Behind the Gold Glove, by Dwight Evans with Erik Sherman is available for purchase at all major bookstores and on-line sites.