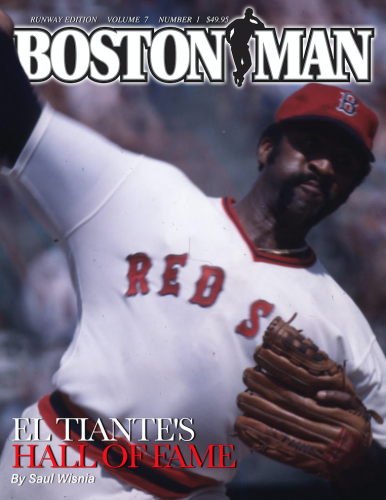

The architect of one of the best five year runs as a starting pitcher in Boston Red Sox history, Luis Tiant won 96 games with a 2.88 ERA from 1972-1976, including being the ace of a team that came within an eyelash of winning the 1975 World Series.

And even with the Baseball Writers’ Association of America once again (inexplicably) failing to recognize Tiant’s rightful enshrinement into Cooperstown, the legacy he leaves -both on and off the baseball diamond- will forever be El Tiante’s Hall of Fame.

LUIS TIANT wanted a house in the suburbs.

Given that he had a wife and three young kids, and was making a nice salary as an ace pitcher for the Red Sox, this seemed like a perfectly reasonable proposition. He found a place in Milton, a town with good schools and not too far a drive from Fenway Park. It had a big yard, a pool where he could entertain his friends and teammates, and enough room to comfortably fit Maria, the kids, and also his aging parents—if he could ever find a way to get them out of Castro’s Cuba.

There was just one problem with Tiant’s version of the American Dream. This was 1974, and Boston was exploding with racial tension. It didn’t matter if he was the great El Tiante, an athlete so popular that fans screamed “LOO-EEE! LOO-EEE!” every time he walked in from the Fenway bullpen to start a game. To some of his prospective neighbors, and perhaps some of those same fans, he was still just another guy with skin as dark as the schoolkids getting bused into Southie to desegregate the Boston Public Schools.

Those kids were met by screaming mobs wielding hateful signs and rocks to ward off change. The stand against El Tiante was more subtle, and not splashed across the front pages. It still stung.

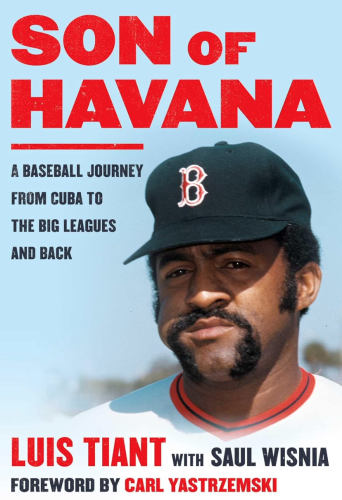

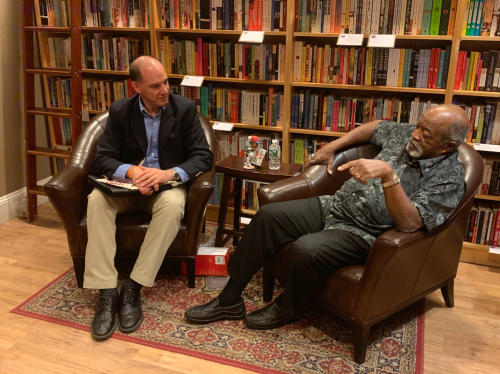

“After I had found the house, and asked the real estate agent for a price, she said it was no longer available,” Tiant told me in 2017, as we were working together on his memoir, Son of Havana. “The owner had decided not to sell. The truth, I found out, was that some people in the neighborhood didn’t want any more Black people living there. They already had one a block and a half away from this house; one was enough.”

Not for Tiant. His wife loved the house. His kids loved the house. The guy everybody on the Red Sox agreed was the glue of the team on the field and in the clubhouse was not about to let a few Archie Bunkers deny his family the happiness they deserved. He had already been through that back in Cuba, where he was refused entry into his hometown’s most popular club due to his family’s modest status—and then told the guys at the door to shove it when they offered him VIP treatment upon his becoming a national hero.

So Tiant didn’t get mad at those narrow-minded Miltonites. He got even.

“I fooled them,” Tiant told me with a sly smile. “I went to the house myself, knocked on the door, and a lady answered. She was Puerto Rican, and it turns out she and her husband—who was white—were the owners. When I told her how much I liked their home, she made sure that we were able to buy it. I guess she understood.”

The Tiants got their dream house, but things were not always easy. A pack of hot-rodding teens took to knocking over the family’s garbage cans, until Luis chased them down one night and told them he’d use the gun in his pocket if they ever tried that shit again. The local police chief, like all cops a big El Tiante fan, begged him to just shoot out their tires rather than anything more drastic.

Another time Luis was raking leaves when a woman stopped her car and rolled down the window. Mistaking him for a gardener, she asked if he was available to help with her lawn. He just smiled and said he appreciated the offer, but his own yard was enough for him.

Eventually, however, Tiant won them all over. He was one of those people who collected friends wherever he went. Back in the minor leagues, playing in the Deep South with a Cleveland Indians farm club, he spoke no English and was shunned by both the home fans and his own teammates—white and Black. The first to befriend him was the lone Jewish guy on the team, Barry Levinson, and the two outcasts remained close for 60-plus years. Eventually Tiant got the others behind him, too, the fans by pitching a no-hitter and his teammates by breaking up long bus rides with his humor.

It was a similar story in Milton. Soon after the family moved in, Tiant’s son Luis Jr. remembered for our book, neighbors were routinely stopping by to say hello. A key Tiant victory at Fenway would lead to the backyard being filled with celebrants listening to merengue, salsa, disco, and old funk late into the night while dining on Maria’s wonderful home-cooked food. There would also, of course, be plenty of El Tiante’s trademark cigars on hand.

And by the fall of 1975, after the Man of the House had pitched the Red Sox to the American League pennant and authored two World Series wins against the mighty Cincinnati Reds, the good people of Milton decided to throw their new favorite son a parade. The family rode through the streets in an antique touring bus, El Tiante dressed to kill in a green leisure suit, and then returned to their house with Senor and Senora Tiant—the parents Luis had indeed gotten out of Cuba that summer, thanks to the intervention of another friend collected along the way: Massachusetts Senator Ed Brooke. (It didn’t hurt that Luis Tiant Sr. had also been a great pitcher, and Castro a baseball fan.)

**************************

THE family grew a little bigger around that same time. Johnny Papile was the young son of an MDC police officer who spent 38 years on the force and lived in nearby Quincy. Tiant and Johnny’s dad, Leo, got to know each other, and when Tiant heard in 1973 that Leo’s wife had died of cancer—and Leo was grieving by burying himself in his work – Luis and Maria stepped in to help young Johnny.

“With my father’s blessing, the Tiants started giving me meals, taking me to and from school, and basically adopted me as their fourth child,” Papile recalled for Son of Havana. “This was during busing, and my father was dealing with all this crazy stuff every day. One time he got hit with a brick in Southie, and he heard the ‘N word’ and everything else all the time. But here was his kid, in the middle of busing, sitting with the Tiant family at ballgames. The whole thing was incredible.”

Years later, on Christmas break from college, Papile went down to visit the Tiants in Mexico City, Maria’s hometown. It was there, while in the Mexican League, that Luis had first met his wife of nearly 64 years—catching her eye from the stands and blowing her kisses as she played softball with a local team in the summer of 1960. Maria wondered if he was crazy, but after dancing with him a few days later, she was hooked, too.

Now Cupid’s arrow would strike again.

“Luis and I were walking to the store one day, and I literally fell in love at first sight with a girl who was visiting the daughter of Luis and Maria’s neighbors,” Papile told me. “Luis helped me to meet her.”

The object of Papile’s desire, however, spoke no English—and Johnny no Spanish. The Tiants served as interpreters, and when the pair were married Maria walked Papile down the aisle. Today he still calls her Mom, and the Tiant’s youngest son, Danny, still calls Papile “my white brother from another mother.”

These were the stories I was thinking about Sunday night, while waiting for the vote to come down. The Veteran’s Committee of the Baseball Hall of Fame had already failed to select Luis for enshrinement on several other occasions, and his statistics— which match up quite nicely with a number of other pitchers already in Cooperstown—had remained unchanged since he threw his last pitch in 1982. There was no reason to imagine the vote would be any different this time around.

One thing was different, however. The man at the center of the first baseball games I can remember attending at Fenway Park, who had gone from a childhood hero to a co-author and dear friend, would not be there to commiserate with if he was once again snubbed—or celebrate with if his 229 wins, 49 shutouts, 187 complete games, and status as one of his era’s greatest clutch pitchers finally turned the vote in his favor.

Tiant died on Oct. 8, just nine days after hearing his name chanted at Fenway for the last time while waving from the “Legends Suite” during the 2024 season finale. A few hours earlier, I had hugged him at El Tiante’s Cuban Grille outside the ballpark, told him I loved him, and promised I’d be up to visit he and Maria in Maine soon.

So when the vote came in, and Luis was again denied, I got to thinking some more. While statistics and championships are most often used to measure an athlete’s status as an all-time great, worthy of a plaque hanging in a grand, high-ceilinged hall, Tiant felt an individual’s character and kindness was more important than being able to write “Hall of Fame, 2024” underneath his signature on baseball cards and glossy photos.

Everywhere the two of us went after Son of Havana was published in 2019, people approached with stories of wonderful things Luis had done for them (or their son, daughter, father, or mother) years before. Luis would smile, nod in recognition, and give their hand a squeeze. I knew there was no way he could possibly remember all these prior encounters, and I’m sure the people knew it, too, but that didn’t matter. The gesture now was as real as the kindness he had been way back when.

But it’s not just the people in the stands and at book signings who felt this way; it’s the people Tiant played with and against as well. Here are a few reflections interviewees shared for the book:

“I’ve said it before and I’ll always say it: If you wanted one person to start in a big game, it would be Luis Tiant.” —Carl Yastrzemski

“People ask me who my favorite pitcher was, and it was him. We had a special relationship where we fed off each other; we understood each other. We demanded things from each other—and expected things from each other.” —Carlton Fisk

“The thing about pitching is that it’s a blank canvas. Every game is different, and you try and draw or paint the best picture you can paint on that particular day, and then you start to do it over time. Luis was very good at that. Luis Tiant looked like he woke up in the morning to do what he was doing.” —Jim Palmer

“He always brought some joy to the game, no matter how he pitched or what he did. He used his sense of humor not only to take the pressure off of us players, but he always had a comment for each individual on the team that brought some laughter to the ballpark.”—Bernie Carbo

“Luis is not a guy who would stand up in the clubhouse and make a speech. He led by his actions, and those are the kind of leaders I like. I don’t want a guy to get on a stump and tell me what to do. Luis would just grab the ball, and you couldn’t get it away from him.” —Fred Lynn

“He was a toreador—a bullfighter. He was flair. He was kind of like those lizards that can throw their throats out and scare you to death, and then throw the ball. He was a Komodo dragon.” —Bill Lee

“He has all the qualities that people admire in somebody. Add to the fact that he is a professional athlete in a local scene like Boston, and it just adds credence to the kind of person that he is—because he never ever let his core values ever get away from him.” —Jim Lonborg

“Watching him was like watching a conductor the way he orchestrated things out there—deciding who was going to do what. Being a pitcher, you’re always taught to repeat your same mechanics. Well, he didn’t; he threw from so many different angles, you didn’t know where he was coming from.” —Tippy Martinez

“It’s a complete sin that Luis Tiant is not in the Hall of Fame. Luis was the best right-hand pitcher I ever saw, and I pitched in St. Louis one year with Bob Gibson.” —Stan Williams

A FAVORITE recollection, one that spoke to Tiant’s best qualities, was shared by Orioles pitcher Scott McGreggor. It revolved around a pregame moment in Baltimore during the 1979 season, the first after Luis had departed as a free agent for the Yankees upon being denied a two-year contract by the Red Sox front office.

“He had a great sense of humor, but he had a great heart too,” McGreggor told me. “I had pitched a game, and my elbow must have been a little bit sore or something like that. It was written in the paper, and the next day I’m out on the field during batting practice and Luis comes out and yells at me.

“Hey amigo!,” he shouts, then comes over.

“Your elbow still sore?”

“Yeah,” I say. “It’s still a little sore.”

Then he immediately tells me what to do, how to fix it, where to ice it.

“You’re on the other team,” I say. “What are you telling me this stuff for?”

“Here the Orioles and the Yankees are battling it out, we’re not close, and he’s coming over telling me what to do to help my arm. I remember thinking at the time, “This guy is pretty special.” He just cared about people, and he cared about the fraternity of pitchers. It was a great introduction to a great man.”

*************************************

THOSE who took in Tiant’s wisdom during his more role as a special instructor with the Red Sox got the same treatment. He collected them as friends—and admirers—as well.

“Luis is a legend, someone we respect and someone we look up to. It’s hard to imagine, when you look at him, so many things he did that were great for baseball, in his time.” —Pedro Martinez

“He’s been like a father to me. He’s in Boston most of the time, so before games and after games I have the opportunity to sit with him and chat. He’s taught me everything. I always listen to him and what he has to say; it’s been great to have the opportunity to have him on my side.”—Eduardo Rodriguez

“Luis Tiant is the personification of Cuban baseball, the epitome of old-school pitching, and a living, breathing icon of Red Sox baseball. To have Luis with the Red Sox to offer his insights, instruction, personality, and to serve as an example to our young pitchers and players has been a priceless asset to the team and a factor in its success in the 21st century. He is a jewel.”—Larry Lucchino

THAT was why, when asked his feelings immediately upon Tiant’s shocking departure for New York, Yastrzemski said the front office “tore out our heart and soul” by failing to retain him. It’s also why El Tiante may have been the one Red Sox player never booed when returning to Fenway Park in pinstripes. That in itself is worthy of a plaque.

“Nobody was a tougher competitor—or a better teammate,” Yaz said in the foreword to Son of Havana. “He meant so much to us, and to the fans. We all loved him.”

So did the 8-year-old kid lucky enough to go from cheering himself hoarse for Tiant at the ’75 World Series to smoking cigars and toasting our friendship over Maria’s Cuban coffee. We never got to pop that celebratory champagne, but that’s okay.

When it comes to a life well lived, El Tiante gets in on the first ballot.

***

Saul Wisnia is the co-author, with Luis Tiant, of Son of Havana: A Baseball Journey From Cuba to the Big League and Back. He is also the author of Miracle at Fenway, Fenway Park: The Centennial, and numerous other books, and since 1999 has been senior publications editor-writer at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.