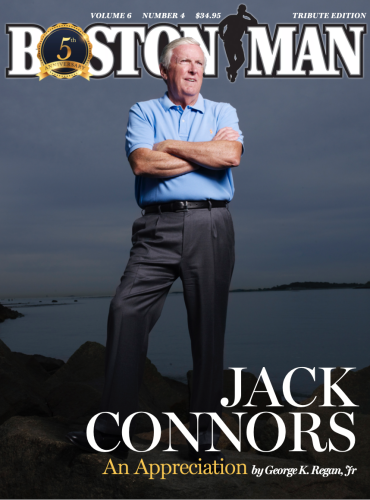

WHAT can you say about a man who built one of this city’s greatest companies, whose reach in the advertising world stretched around the globe, but who knew his highest accomplishments, by far, were his unceasing efforts to help children and families living in poverty?

About a man who garnered the highest respect and deepest admiration of the city’s most influential power brokers and politicians, but whose ego was non-existent?

About a man who never sought publicity except when it was necessary to help bring in some of the many millions of dollars he raised to help those who, by circumstance or geography, were less fortunate than him, not to mention the millions of his own he gave to those charitable endeavors?

About a man who never forgot his friends, or the feelings of others?

When Jack Connors — corporate giant, philanthropic leader, Grand Bostonian — died last month after a brief illness, thousands and thousands of words were written and spoken about the kind of man he was. Adding my own, I can do no better than this: A devout Catholic, Jack embodied a verse from the Bible: “And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.”

The charitable endeavors that Jack started or supported have transformed the lives of thousands of people, like the countless inner-city children who were mentored, exposed to nature for the first time, and grasped the possibilities of a better future thanks to Camp Harbor View, the shining jewel that Jack founded on an island in Boston Harbor.

But his generosity and kindness were not limited to formal fundraising campaigns. Jack routinely opened his heart, and wallet, to friends, acquaintances, and even strangers whose paths, through some Divine Providence, eventually crossed with Jack’s when they most needed help.

I know this because I was one of them.

More years ago than I care to remember, when I was 24 years old, I scurried into Boston City Hall for an interview I somehow had managed to get with Mayor Kevin White, who was looking for an assistant to the assistant to the assistant to the press secretary. In anticipation of the meeting, my mother and I had gone shopping for new clothes; I’m sure I thought I was dashing as I showed up for the interview in my brand new underwear, shirt, tie, and pants that were a little too short. There I was, in the mayor’s magnificent office with a huge window overlooking Faneuil Hall, with the man who had rugged movie-star looks and was considered, along with New York’s John Lindsay, one of the country’s top urban mayors. To say I was nervous is the understatement of all time.

The mayor’s look more or less said, “YOU want to be in my press office?” The meeting was a complete disaster. It lasted all of five minutes. I later found out the mayor’s preferred candidate was a guy who had written for the old Washington Star newspaper.

But I did have two supporters in the administration. Bob Kiley, a Notre Dame graduate and former CIA operative who was Kevin’s deputy mayor, and Frank Tidman, the director of communications. They pulled me aside, assured me they liked me, and said they would hire me but they were going to hide me from the mayor for six months. I was like a stowaway, only I wasn’t in the belly of a ship, I was in the bowels of City Hall.

My City Hall rabbis Kiley and Tidman also arranged for me to meet a guy named Jack Connors, who along with three partners had founded Hill Holiday, an advertising and communications firm, several years earlier. Jack was a confidant of Mayor White, an informal but influential advisor on communications strategy. If I was going to be in the press office, I had to have Jack’s blessing.

For the second time in a few weeks, I put on new underwear and a new shirt, jacket, and pants that finally fit. I set off anxiously to meet someone who was so far above me in terms of polish, panache, and duende, I might as well have been a scared mouse in the corner. When I met Jack, I again had the feeling that the person I was meeting had appraised me and concluded, “you’ve got to be kidding me.”

Tellingly, Jack also was afraid to tell the mayor I was working for him.

Around that time, Kevin White’s name was being floated by Democratic Party bosses as a possible candidate for the Presidency in 1976. The mayor went on a ten-city tour to explore national issues and see how his candidacy might be received. I was dispatched to do advance work in all 10 cities and got to each stop a day ahead of the mayor. I was told to avoid him, but, unfortunately, he caught up to me in Southfield, a suburb of Detroit. He laid eyes on me and said, “What are you doing here?”

Everyone still must have been afraid to tell him I had been hired.

As Kevin began his nascent campaign, things were not going great back home. Busing was still a divisive issue in Boston and the work of urban renewal that was dear to the mayor was far from finished. Eventually Kevin bowed out of Presidential consideration and got back to rebuilding the city he loved. I went on to work for Jimmy Carter’s campaign for a while, and then returned to the mayor’s press office. This time, the mayor actually knew I was working for him, and I eventually became his chief press secretary as well as director of communications for the city. Kevin used to say that he had the best job in the city, but that I had the second best. I am proud of the work we did together.

I’m also proud that, over the years, Jack Connors became my friend, mentor, and advisor as well. I’m not ashamed to say that he saved me from myself on many an occasion.

Fast forward to 1984, and Kevin White, having decided not to seek a fifth mayoral term, was leaving office. And with him went my job, the second best in the city. Faced with trying to figure out my future, I met with Tom Winship, the legendary editor of the Boston Globe, and Bob Bennett, the founding general manager of Channel 5, about possibly becoming a reporter. But they raised another possibility – opening my own communications shop.

Once again, I turned to my friend Jack Connors to get his advice. Hill Holiday, by that time, had grown into a global advertising powerhouse under Jack’s leadership. We met in his office at the top of the John Hancock Tower. It was a lunch meeting. I walked in and there were two Diet Cokes and two tuna sandwiches on the table. This wasn’t off to a good start – I hated tuna fish.

I told Jack I was thinking of starting my own PR company. He told me it was the stupidest thing he’d ever heard (at least I wouldn’t get a big head coming out of this meeting). Instead, Jack offered me a job running public relations in Europe for Hill Holiday’s Wang Computers account. Ten minutes later, my tuna sandwich untouched, I left.

By the next day, I had reached a decision. I would go out on my own. I was going to start Regan Communications. But I had to let Jack know. I called him, and suffered what was known back then as a “Jack Attack.” He lit into me.

“Do you even have any money?” he asked me. I answered that I had $25,000 from my city retirement account, but probably needed another $25,000 to get off the ground. He thought it over, and, against what must have been his better judgment, told me, “I’m in for $25,000, but I know I’ll never see that money again.”

Along with all his other attributes, Jack Connors was a great businessman. He was not about to see his generosity wasted by a guy who had no idea how to run a company. So, every Monday morning at 8 o’clock for the next year, I had to meet Jack for breakfast at the Copley Plaza hotel, and over Diet Cokes and English muffins, he taught me the nuts and bolts of business leadership. Budgets, salaries, strategy, contracts… you name it, he tutored me on it. If it were not for Jack Connors, I never would have been able to start my own business, let alone succeed at it.

Over the years, I knew I would occasionally drive Jack crazy. But I didn’t always know how crazy.

One day, decades after I started my own business, I was having dinner with Jack at Davio’s and he told me a story.

Back in the day, during the Kevin White administration, Hill Holiday had signed up the Boston Globe as an advertising client. One of the conditions of the Globe giving Jack their business was that he was supposed to stay out of politics, at least publicly. The newspaper couldn’t be affiliated with someone who was seen to be a partisan with one candidate or party.

At the same time, I was pitching Kevin as a serious Presidential candidate to various reporters. At one point I was asked what big names supported Kevin’s bid. Naturally, who did I mention, but Jack Connors. When that made the news, the Globe was not happy. Jack almost got fired as the Globe’s advertising genius, thanks to me.

To Jack’s credit, he did not tell me that story until 30 years later. He had not wanted me to feel bad, he explained. I had forgotten that I dropped his name to the reporter all those years ago, and I had no idea of the tight spot I’d put him in. “It sounds like something I would do,” I acknowledged.

That is the person that Jack was. Your feelings were paramount to him. If he cared that much about not hurting my feelings, I can only imagine how much it tore at his heart when he saw children and families living in poverty, in fear, without hope. That was the passion that drove Jack Connors to be a force for good. That was what motivated him to do what he could, and to give what he had, and to get his counterparts in business and civic life to give what they could, to help those upon whom fate had not smiled.

It is why, despite the best intentions of many other good people, there is a hole in Boston’s heart today. Jack Connors, man of faith and master of communications, never forgot that the most important words were those in Scripture that taught him to love others as his Lord had loved him. Farewell, my friend, to whom I owe so much.