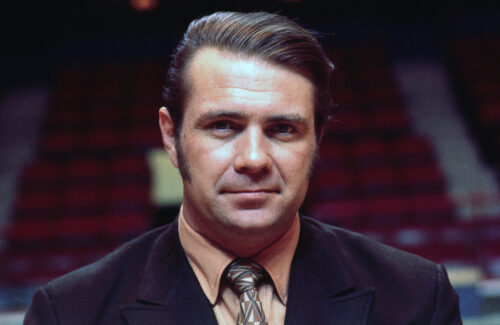

There will never be another like him. Tommy Heinsohn embodied and represented everything it meant to be a Boston Celtic -perhaps even more than he himself could have imagined. In this cover story, HOF journalist Bob Ryan reflects on the Remarkable Life of Tommy and the things that made him so endearing to the city of Boston.

Hall of Fame player. Hall of Fame coach. Champion Insurance salesman. Colorful broadcaster. Artist. Staunch Players Union leader. Engaging companion. Most of all, the Ultimate Celtic.

Who else checked off all these boxes other than Tommy Heinsohn? The answer, of course, is no one.

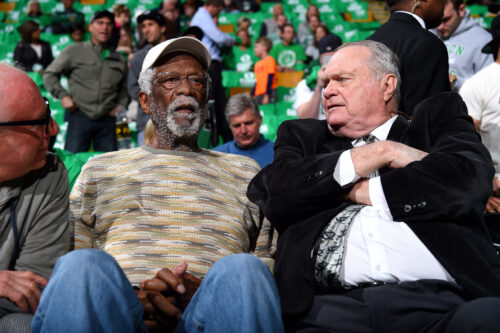

Red Auerbach was the Godfather. Bob Cousy was the franchise savior. Bill Russell was the greatest player. But no one else served the organization longer, or with more passion. Tom Heinsohn came to the Celtics as a territorial first round draft pick out of Holy Cross in 1956. He died while maintaining a role in Celtics TV coverage on November 9, 2020. There was never a moment when he wasn’t all-in with the Celtics, either directly or emotionally. Through it all, every last corpuscle was green.

“He looked at the world through green glasses,” says long time broadcast partner Mike Gorman.

The modern audience knew him best as a, shall we say, somewhat less than objective observer behind the microphone. (We’ll get to Tommy and the treacherous men with the whistles). But that involvement was only Phase III of his Celtics life. Phase I was a 10-year span as a high-scoring forward who was a member of the first eight championship teams, a player good enough to warrant induction into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1986. Phase II was a head coaching career that included two NBA championships and a 68-win season that were it not for an unlikely injury to John Havlicek in the Eastern Conference Finals would undoubtedly — sorry, Knicks and Lakers — have concluded with another championship. He was inducted into the Hall a second time in 2015, this time as a coach. Only John Wooden, Lenny Wilkens and Bill Sharman share that particular dual player-coach Hall of Fame distinction.

Phase I

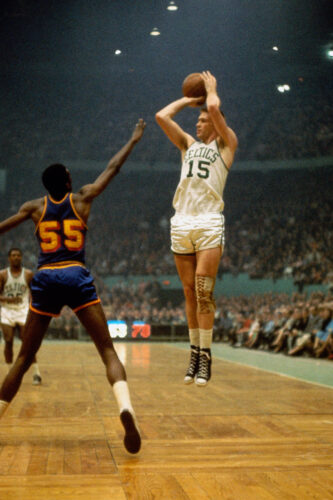

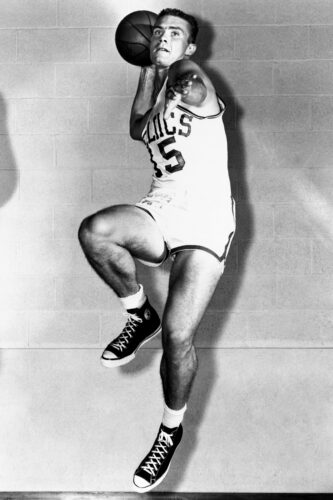

Tommy’s swashbuckling style of play left an indelible memory for those fortunate enough to have seen him play. He was very much a player of his time, a 6-7 high school and college center, his two primary offensive weapons being a line drive jump shot whose arc was developed due to the low ceiling of a high school gym, and a hook shot, both stationary and running.

Ah, the running hook. That’s the one separating himself from the pack in the 50s and 60s. He loved the hook, and was amazingly adept at something unknown to a modern audience. Tommy Heinsohn loved throwing up hooks from the corner.

He was oh-so-proud of that hook. The title of a 1988 book he did with collaborator Joe Fitzgerald was “Give ‘Em The Hook.” The cover featured Tommy emerging from a pile of basketballs with a basketball preparing to be released from over his right shoulder and a microphone in his left hand. Anyone who followed the Celtics over the years retains the frequent sight of the sports coat-clad announcer dazzling the young’uns with hook shots from absurd distances during the pre-game.

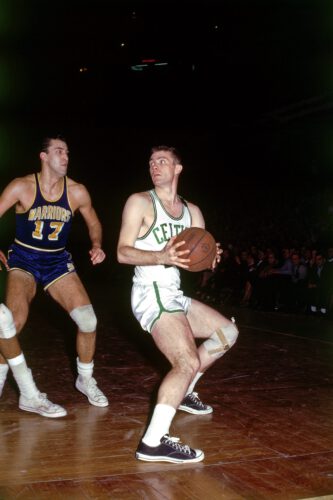

He and Russell were fellow rookies on the 1956-57 Celtics, but Tommy Heinsohn, not Bill Russell was the Rookie of the Year. Given the circumstances of his first press Boston conference after they each were selected in the 1956 draft, that mist have been very rewarding. Russell was not going to join the team until December, following the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. So there was Tommy, the local pick from Holy Cross, expecting to be explaining himself.

However…

“It was the damnedest press conference in the world as far as helping a kid’s ego goes,” he recalled. “Almost every question they asked me was about Russell. Had I seen him play much? Was he as good as everyone thought?”

But Tommy shrugged it all off and went on to putting up 16 points and 10 rebounds a game. The Celtics were already in first place by the time Russell arrived in December. Cousy was en route to winning the MVP and Tommy was en route to being the Rookie of the Year.

If anyone doubted the precocity of the two rookies, complete evidence was submitted in Game 7 of the 1957 Finals. It was an epic. The Celtics needed two overtimes to subdue the Bob Pettit and Cliff Hagan-led St. Louis Hawks, and the key players were Russell, with 19 points, 32 rebounds and innumerable great defensive plays, and Heinsohn, who poured in 37 points and grabbed 23 rebounds before fouling out with two minutes left in the second OT.

“I never saw such a game played by a man under pressure,” lauded teammate Bill Sharman. Asked if he ever felt pressure on the court, Heinsohn replied “Pressure? Sure I felt pressure,” he said. “But if the shot’s there, take ‘em. What the deuce is the guy supposed to do wit the ball? Eat it? Let them eat it if they want to.”

Tommy was really enjoying the moment. He went around the locker room, saying “Want to be my agent? Sign me up quick. I’m going for a big price.”

Not for nothing was he nicknamed “Tommy Gun.” Passing was always the second option.

And that was actually quite okay. Red handed out job descriptions. Cousy was to run the team. Russell was to rebound and play defense. Sharman and Heinsohn were there to score. But Tommy could do more than that.

“He was the ideal forward,” Red once said. “He could do it all: great offensive rebounding, great moves, great shots — including a beautiful soft hook, even great defense when he felt like playing it.”

Tommy had another specific role on the squad. Red fancied himself as a champion psychologist as much as a basketball X and O man. As a student of human nature he was the antithesis of Vince Lombardi, of whom Packer Henry Jordan once said, “He treats us all the same — like dogs.” Red had different approaches for different players.

In this context, Tommy and Jim Loscutoff were the DWB — Designated Whipping Boys.

“He couldn’t yell at Russell or Cousy, because they had too much pride.” Heinsohn explained. “And if you yelled at Sharman, he’d get the red ass. If you yelled at (Frank) Ramsey, he’d take it to heart. If you yelled at Sam, he’d brood. If you yelled at KC. Satch, (Willie) Naulls or Havlicek, they’d be hurt and embarrassed because they were basically quiet people.

“So he would give it to Loscy and me every (censored) night. But we really didn’t care. We knew what he was doing and why.”

Tommy even one-upped Red on a night when they entered the locker room at halftime with a substantial lead. “As soon as the door opened,” he recalled, “I jumped up and said, ‘Okay, Red, I didn’t shoot. I didn’t rebound. I didn’t block out. What else didn’t I do’?” Red had no choice but to join in the laughter.

The best thing is that he cared about his teammates more than himself. It did not go down very well with either Red or owner Walter Brown when the 1964 All-Star Game, scheduled for a rare national telecast, was threatened because the players were threatening to strike if they were not granted recognition for their union. The leader was none other than Tom Heinsohn. The game did go off after the players were placated, although Walter Brown did denounce Tom Heinsohn as a “heel.”

Phase II

Chronic bad knees that would surely have been helped out by today’s superior medical knowledge led to his premature retirement at age 30 following the 1964-65 season. (A heavy smoking habit didn’t help, either). Unlike many others, Tommy had been planning for life after basketball. He made an immediate transition into the insurance business, first becoming an award-winning salesman and then becoming a senior executive who showed others the ropes. And when the Celtics got themselves a nice little local TV deal, he was a natural commentator. There was never a doubt as to what approach he would take. Each game was the Boston Celtics vs. the whole entire damn world, embodied by the two officials.

The Celtics had continued being the Celtics, rebounding from a loss to the Philadelphia 76ers in 1967 to winning two more titles in 1968 and 1969. But there was a bombshell announcement the summer of ’69. With two titles, an Olympics gold medal and 11 NBA titles in 13 opportunities, Bill Russell had ceded to retire. Oh, and he just happened to be the coach, as well as the key player.

It didn’t take long for Red Auerbach to anoint a successor. He selected Tom Heinsohn, and never mind he had never coached a day of anything in his life, not even what we then called Biddy Basketball.

Talk about a rugged assignment. Russell and the great Sam Jones were gone, and he also had the responsibility of coaching the likes of Havlicek and Satch Sanders, men he had played with not long before.

The team simply wasn’t very good, and here was a coach going through a classic OJT experience. The final record was 34-48, with the team missing the playoffs for the first time since 1949-50, the year before Auerbach arrived. But there were still some good moments. The New York Knicks had steamrollered their way through a 60-22 season on their way to a championship. But against the otherwise mediocre Boston Celtics they were 3-4. It was the only season series they didn’t win.

The key for Tommy was that he wasn’t under pressure to win another championship, or even make the playoffs. This is where Red came in. He had hired Heinsohn because he had respect for Tommy’s intelligence and basketball IQ. He was always ready for questions.

“Publicly, I suffered through that first season,” Heinsohn explained. “But privately, I knew I had all the time I needed, thanks to Red. If you don’t know for sure you’re the boss, you begin running scared and second-guessing yourself. I never had to do that. Red stayed clear of my locker room, my practice floor and my players, unless I asked him for help. He put me in charge, and then stepped back and let me do my own thing. And he made sure I knew he was behind me, every step of the way.”

There were, in fact, a couple of good young players in Jo Jo White and Don Chaney, and when Dave Cowens was drafted in the 1970 draft the Celtics had found their next transformative player.

Tommy always knew what he wanted to do, and that was to run. Sound familiar, millennials? How many times over the past three decades or so have you heard Tommy the Broadcaster exhort the Celtics to “push it, push push it?” It’s the basketball approach that was instilled in him by Red, and he was determined to instill it in his teams.

Cowens could rebound and he could run. He was ideal for Tommy’s chosen method of play. Tommy’s teams were never particularly big. But they were quick and they were relentless.

Here. He’ll explain.

“The fast break is an attitude,” he loved to say. “The idea is to keep pressure on the defense and attack their desire to win….the Celtics go after another team’s conditioning, especially the big men. The Celtics want to wear out the big men and catch them loafing by the second quarter. How long is it going to take for the poor suckers who do get back on defense to get pissed at their teammates who aren’t hustling? ’Screw you,’ they’re going to say. ‘I quit.’ The Celtics want to break down the other team’s morale and cause dissension.”

Dave Cowens was God’s gift to Tommy in this regard. Many the night Dave Cowens ran and ran and ran and the likes of Kareem Abdul Jabbar, Wilt Chamberlain and Bob Lanier couldn’t, or wouldn’t, keep up.

It was Tommy’s team, all right. Way out West the Celtics had picked up a convert (and covert) admirer. It was the young Bruce Jenkins, whose father was famed composer, arranger and orchestra leader Gordon Jenkins and who would grow up to be an award-winning sports columnist. After first being frustrated by watching his Lakers lose to the Celtics, he eventually fell under their spell.

“I got the feeling the Celtics were invincible,” he explained. “I had countless nights of quiet satisfaction at the Sports Arena, savoring the Celtics’ victories while those preposterous L.A. sports fans whined and groaned around me. When Heinsohn was coaching, he had a way of gathering all of that Celtic Pride into one gesture. Invariably, it would be a night of screaming and ranting for Heinsohn; the fans’ disdain for him knew no bounds. And then when it was over, the Celtics won by about 11, and as he walked off the court — always around the same place — Heinsohn would loosen his tie. Oh, the magnificent arrogance of it all.”

Phase III

Two championships later Tom Heinsohn entered Phase III. No one foresaw it would last the rest of his life, or that, more than Cousy, more than Russell and even more than Red, he would become the public custodian of All Things Celtics, bringing home the good news of championship coaches Bill Fitch, K.C. Jones and Doc Rivers and storied players such as Larry Bird, Kevin McHale, Robert Parish, Dennis Johnson, Bill Walton, Paul Pierce, Kevin Garnett, Ray Allen, and Jayson Tatum, while making a folk hero out of a fringe player named Walter McCarty. I mean, who will ever forget “I love Waltah?”

No one will miss Tom Heinsohn’s company more than Mike Gorman, his broadcast partner of nearly four decades. Tommy had cut back in recent years as age and deteriorating health had taken him off the road, but he was still front and center for home games until COVID-19 entered everyone’s life.

“The way things are, there are certain places where I haven’t had a chance to miss him yet,” explains Gorman. “For example, the press room before the game. I can still see him coming down the hallway, with that 15 to 20 degree lean (Tommy had an unmistakable walk) and then sitting down for a meal and conversation.

The partnership actually began when Mike was ensconced in college basketball. “We did a few games together,” Gorman recalls, “but he was kind of indifferent. He really didn’t care about UConn or Providence. He was so much more passionate about the NBA.”

Gorman never tires of telling about their very first Celtics telecast.

“It was against Indiana,” he begins. “I had all my game notes. I had the three-colored pencils, the statistical and personal info and all that. Now remember we were in the original first balcony press row then. Tommy comes in and says ‘What’s that shit?’ He proceeds to take my notes, crumble them up and throw them over the balcony onto the seats below. ‘We don’t need that stuff,’ he growled. ‘We will just do the game in front of us.’’ And that’s the way it would always be.”

Tommy was certainly never a big fan of the referees when he coached, but when he became a broadcaster it was as if he had declared war on the entire profession. “Tommy would say. ‘There are three teams out there, and two of them are against us.’” Asked if in all those years Mike Gorman could recall even one instance in which Tom Heinsohn acknowledged that the Boston Celtics had indeed been the beneficiaries of a terrible call in their favor, Mike Gorman has a one-word answer: “No.”

“He once had to be separated from a referee,” Gorman points out. “One night a referee was coming out of their dressing room after a game and he was complaining about that damn Heinsohn. Tommy just happened to be walking by and he heard it. And he went after him.”

No mention of Tommy Heinsohn is complete without discussing Tom Heinsohn, the Artist. It’s doubtful if any other NBA personage has taken his life’s inspiration from Vincent Van Gogh. But here is Tom Heinsohn on the French master:

“I began reading about Van Gogh a long time ago, when I first got involved in art,” he explained. “I guess what his life story has always said to me is that if you’re going to be worth anything, if you’re really going to be good at what you do, you have to believe in yourself and what you’re doing and not be subject to the whims of other people. Oh, you can listen to what they have to say, but ultimately it’s you who has to make the decisions.”

So there was a lot more to Tommy Heinsohn than basketball. Among other things, he very likely took the word “inculcate” with him to the grave. He used it all the time. He explained that he tried to “inculcate” a fast break mentality into his players; in other words, to instill an idea.

The hope here is that this writer has “inculcated” into your mind the idea that Tom Heinsohn was a unique figure in basketball history. There are no Tom Heinsohns on the horizon.

***