Red Sox legend Dwight Evans is one of a kind. He talks about 19 seasons in Boston, the teammates who helped make him great, and his sons’ quiet battle against a rare genetic disorder.

“I loved coming to the plate late in the game with men on base,” says Dwight Evans, the Red Sox legend who owned right field in Fenway Park for most of the 1970s and 1980s. “I thought I was really good in that position. You’d have the crowd into it, and I really couldn’t tune out the noise. I used it to my favor, whether we were at home or on the road. In those situations, though, I always felt like I was in a tunnel — just me, the pitcher, the catcher, and the umpire. I’d know the tendencies of each, and I’d try to lock in on the pitch I was looking for.”

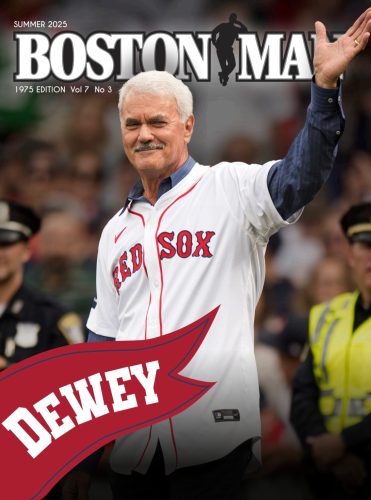

That desire to make the big play and that focus at the right moments served Evans well across 19 seasons in a Red Sox uniform (plus one final campaign in Baltimore). The Red Sox Hall of Famer led the major leagues in extra base hits — and the American League in home runs — during the 1980s, was an eight-time Gold Glover, and a three-time American League All-Star. He’s also the only member of the Red Sox to appear in both the 1975 and 1986 World Series.

Those important traits also served him and his wife Susan through the difficult times of raising — and eventually losing — two sons who suffered from neurofibromatosis (NF), a rare and debilitating genetic disorder.

Known as “Dewey” to teammates, friends, and generations of New England baseball junkies, Evans and his family — who reside in Lynnfield — waged their battle against NF mostly privately. In his 2024 autobiography, “Dewey: Behind the Gold Glove” (written with Erik Sherman), he wrote, “None of my teammates, except for my closest friend, confidante, and mentor in baseball, Carl Yastrzemski — who suffered the pain of losing his own son, Michael, 20 years ago — really knew any of the details or the severity of the situation. In baseball, you talk about the game, you talk about the weather. Nobody wants to hear about your problems. You just don’t share all that much about your family life.”

Evans’ desire for privacy is part and parcel of his personality — dating back to his early youth in Hawaii, and his teenage years in Southern California. “I’ve always been very shy,” he says. “In school, I’d have to do an oral report. I’d have it prepared, but I was scared to death to get in front of people and let them know what I was thinking. I’d get up there, and the teacher would ask me to begin. I’d say, ‘I don’t have my oral report.’ She said, ‘If you don’t give your report, you’ll fail.’ And I’d say, ‘Okay,’ and sit down.’”

Suffice it to say, the shyness has subsided, as Evans serves as a roving instructor during Red Sox spring training in Fort Myers, Fla., and as a regular host of VIP guests in the Red Sox’ Legends Suite at Fenway. He also served for more than a decade — with his wife — as chairs of NF Northeast’s annual golf tournament to raise money seeking a cure for the disease. If you’re lucky enough to spend time speaking with him, you’ll find he’s still an invested ambassador in the cause.

“NF afflicts three times as many people as muscular dystrophy and cystic fibrosis, combined,” Evans says. “The Red Sox gave us a huge donation when I retired — a Yawkey Foundation grant. But they specified: this money is to drive awareness. I have a passion for finding a cure.”

A pre-game ceremony honoring the 1975 American League Champions 50th Anniversary Reunion is held before the 2025 Opening Day game between the St. Louis Cardinals and the Boston Red Sox on April 4, 2025 at Fenway Park in Boston, Massachusetts. (Photo by Maddie Malhotra/Boston Red Sox/Getty Images) *** Local Caption *** Fred Lynn; Dwight Evans; Cecil Cooper

From Oahu to Boston

Evans was born in Santa Monica, Calif., and his family moved to the island of Oahu before he was a year old. He spent 10 years there. “I remember going to school at Kailua Elementary — barefoot, in shorts and a t-shirt,” Evans says with a laugh.

Returning to Southern California, Evans found himself in the San Fernando Valley, northwest of downtown Los Angeles, where he starred in baseball at Chatsworth High School. At age 17, he graduated and was drafted by Boston in the fifth round of the 1969 MLB draft.

“I signed at 17, and I went to Jamestown, N.Y., the New York-Penn league,” Evans says. “I was so young, going to upstate New York was a tough move for me. I’d also had a scholarship offer to play football at the University of Wisconsin. But I couldn’t see myself freezing through winters up there. This was a chance to play baseball in a warmer climate — another transition, the beginning of another life. It was good for me. I got to grow up around some great coaches, some tough coaches. But I adapted. It made me grow up.”

From Jamestown, Evans jumped the next season to Greenville, S.C., and then — in 1971 ‚ to Winston-Salem, N.C. (where he gained the nickname “Dewey” from manager Don Lock). He began 1972 at Triple-A Louisville. “At age 20, I skipped Double-A. It was a big move to skip a whole league,” Evans remembers.

About halfway through the season, Evans was hitting under .200. “The manager came to me and said, ‘If you don’t get your offense in line, we’re sending you down to Double-A,’” Evans says. “I struggled for a couple more days, but then one day, I went three-for-four. From there, I ended up going on a 42-for-68 streak (that’s a .617 batting average) and raised my average from .180 to .240. I ended up hitting .400 for the rest of the season and won MVP of the International League. The Red Sox called me up in September.”

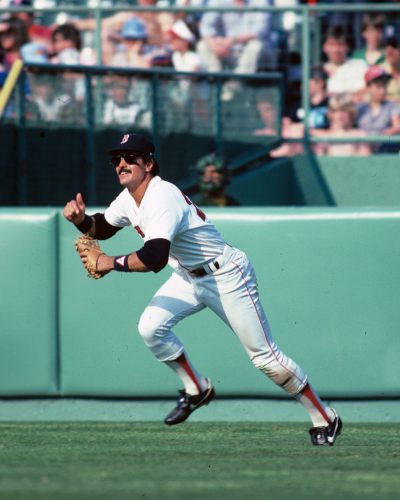

He never looked back, becoming Boston’s starting right fielder in 1973 — a spot he’d hold full-time through the 1986 season. In September 1974, he was joined by a pair of rookies who — beginning the following season — would form one of the best outfield trios the game has ever seen.

Dwight Evans chases down a fly ball during a game against the Oakland Athletics at Fenway Park in 1985.

(Photo by Jerry Buckley/Boston Red Sox)

The Spirit of ’75

“We were in first place in 1974 but had a collapse in mid-August,” Evans remembers. “We brought up Jim Rice and Fred Lynn in the final month — and starting the next year, that changed whole dynamic of the ballclub.”

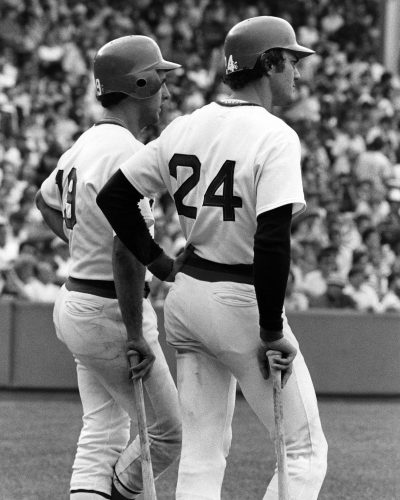

Rice, a Baseball Hall of Fame left fielder, and Lynn, a stellar center fielder and clutch hitter who played the first six of his eventual 17 major league seasons at Fenway, joined Evans in the starting lineup in 1975. “It made us complete,” Evans said. “We had good pitching; we had good players. But those two made it so much better. Jimmy and I played 16 years together — you’ll probably never see that again.”

The Red Sox seized first place in the American League East in May and then went on a hot streak in July to take control of the division. Rice (.309 batting average, 22 HR, 102 RBI) and Lynn (.331, 21, 105) added heft to a lineup that featured Evans, catcher Carlton Fisk, and Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski, while the pitching staff featured Luis Tiant, Bill Lee, and Rick Wise.

Fred Lynn and Dwight Evans wait in the on-deck circle during a pitching change.

(Photo by Boston Red Sox)

It was Lynn, though, whose star shone brightest, winning American League Rookie of the Year and American League MVP. “With Fred, he was like a little Ted Williams,” Evans says. “Everything came so naturally to him. Jimmy and Fred, those two guys, I never saw either of them take extra batting practice. They didn’t need it. I took it all the time!”

Though the team cruised through the American League Championship Series, sweeping the three-time defending World Series champion Oakland A’s, they were missing Rice, who suffered a broken bone in his hand when hit by a pitch on Sept. 21 and would not return that season.

In one of the most revered World Series of all time, Boston battled the Cincinnati Reds to a deciding seventh game at Fenway Park — after Carlton Fisk’s famous 12th-inning home run extended the Red Sox season in Game 6.

But before Fisk’s homer, Evans made a game-saving play in the top of the 11th inning, snaring Reds second baseman Joe Morgan’s long drive and doubling Ken Griffey Sr. off first base.

“I always say that great plays are made before the play,” he says. “If you’re a good fielder, you’re always anticipating. So, on that play, Griffey was on first, and he was fastest guy in baseball at the time. Dick Drago is on the mound, and I’m going through everything: stop Griffey from going to third on a base hit; if it’s a gapper, hit the cutoff man; if the ball is over my head, I have to be willing to go into the stands.”

Morgan’s high line drive was straight over Evans’ head. “So, I turn toward the right field line, because — normally — a ball like that will curve toward the line,” he says. “This one didn’t turn. It just kept going straight, so I’m in no man’s land — on the track, close to the fence, and the ball is behind me — I’ve lost it from my right shoulder, and there’s nothing worse than losing sight of the ball.”

Every long-time Red Sox fan can tell you what happened next. Let’s hear it from Evans. “I just threw my glove up behind me,” he says. “I didn’t see it go in, but I felt it. And then I hit the wall. When I turn around, all I can see is the lights above the third-base line, but I just threw it as hard as I could toward first base. I was off by 20 feet, but Yaz grabbed it and tossed it to Rick Burleson who was covering first for the double play.”

Unfortunately, the magic didn’t continue in Game 7, as the Reds won the game (and the series) 4-3.

“It was a great team,” Evans says. “But Jim got hurt in the last week of the season. I can only imagine what we’d have been able to do in the World Series if he was healthy. Still, we swept the A’s and pushed it to the seventh game against the Reds, and a bloop single (by Reds second baseman Joe Morgan) won the series.”

Evans continues, “What’s sad about it is that group was together another five years and we didn’t play in another World Series. You know, we played a playoff game in 1978 against the Yankees after both teams won 99 games in the regular season. They beat us and went on to win the World Series.”

The starting outfielders for the 1975 Red Sox, Jim Rice, Fred Lynn, and Dwight Evans, pose during spring training.

(Photo by Boston Red Sox)

Gold Glove, Silver Bat, Big Influences

Though it would be 11 seasons until the Red Sox would return to the postseason, the late 70s and early 80s featured some of Evans’ best years. He won all eight of his Gold Gloves between 1976-1985. He was the American League home run leader (and a Silver Slugger winner) during the strike-shortened 1981 season. He was an All-Star in 1978 and 1981. And he grew into a fixture in Boston.

Evans says an adjustment in his hitting plan — prompted by then Red Sox bullpen coach (and future hitting coach) Walt Hriniak — made a huge difference in his offensive game. “When I came up at age 20, they looked at me and at the Green Monster and told me, ‘Grab a piece of cheese (baseball slang for a fastball) and wrap it around the pole!’” he recalls. “They wanted me to be a pull hitter, though my strength was more as a gap-to-gap hitter.”

He adds, “So I was really just using one side of the field until around 1980, when I got back to the middle of the field. That was my strength, and I really found my stroke. It lifted my confidence level.”

Evans says spending 12 seasons playing with Yastrzemski helped him become a pro. “Playing with Yaz was like playing with an older brother,” he says. “He taught me so much about how to play, and about how to play hurt. It’s a 162-game season, so it’s rare you’re not dealing with something. Jimmy and I always say that if we’d only played when we were healthy, we’d have never played. I loved playing every day, and that meant playing through injuries. Through Carl, we learned how to play through pain — and produce.”

Evans also name drops Fisk, Juan Marichal, Tony Perez, and Tom Seaver as positive influences. “Perez (who spent 1980-1982 with Boston) taught me a lot about the game,” he says. “He was the ultimate RBI guy. He was all about driving in runs. So, we’re playing a day game and Tony’s on the bench. I come up with a man on second and nobody out. Gotta hit the ball to the right side, right? Get the runner over? I hit a bullet, right at the second baseman, and he caught it. I come back to the dugout, and I’m getting a lot of positive support: ‘Nice job, Dewey,’ ‘Tough break, Dewey.’ Tony doesn’t say a word. So, I sit down next to him, and he looks at me and goes, ‘You think you did a good job?’ I say, ‘I hit it hard to right side.’ And he puts his index finger up in my face and says, ‘You didn’t do the job.’ Tony’s big belief was ‘Don’t just get them over, get them in.’”

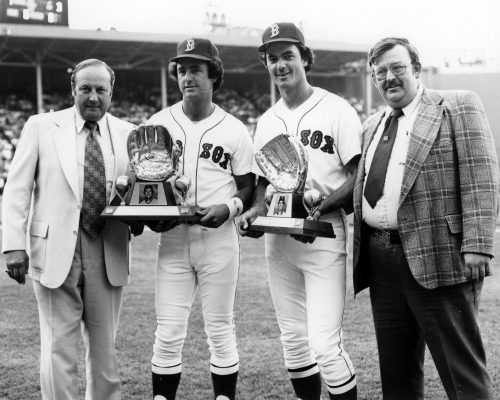

Dwight Evans and Fred Lynn pose with their 1978 Gold Glove Awards before a game at Fenway Park in 1979.

(Photo by Boston Red Sox)

Opening Salvo, Closing Heartbreak

Another fun fact about Evans? He hit four Opening Day home runs in his career, none more memorable than his blast against the Tigers’ Jack Morris in Detroit in 1986.

Evans says, “(Red Sox manager) John McNamara comes up to me in spring training and asks, ‘Would you do me a favor? Would you lead off in Detroit on Opening Day?’ I said, ‘Absolutely.’ I knew I was facing Morris, and I had a dream the next few nights that I hit a home run on the first pitch. Hriniak was the hitting coach by then, and he didn’t like to talk home runs. I told him about the dream, and he didn’t like it.”

He continues, “I came to the plate more than 10,500 times in my career, and not once did I not have butterflies. But that day, leading off in Tiger Stadium with 55,000 people in the stands, there was a legion of butterflies! Walt comes up and asks how I’m feeling. I say, ‘Walt, I’m hitting a line drive to right center.’ He pops me in the chest and says, ‘Dynamite.’ Then, I walk to the on-deck circle and (Red Sox second baseman) Marty Barrett is there. I looked at him and said, ‘I’m going deep on the first pitch.’ I knew Morris was going to come with a fastball, but to turn on that fastball was another thing. The pitch was up, and I hit it out to left center. I couldn’t believe it happened.”

That home run — on the very first pitch of the MLB season (a feat not equaled until the Chicago Cubs’ Ian Happ did it in 2018) — set an auspicious tone for the Red Sox. Like in 1975, Boston took over first place in May and closed on fire, playing near-.700 baseball in September to win the American League East.

The Red Sox upended the California Angels — stealing a dramatic extra-innings Game 5 in Anaheim before closing out the series with a pair of blowout wins in Fenway — to set up a World Series showdown with the New York Mets.

Evans, one of the young guard on the 1975 team, was one of the veteran leaders in 1986. “A lot of what I projected to the younger guys in 1986 was what Carl and Tony taught me,” he says. “But we had a lot of veterans. We had Don Baylor; we had Bill Buckner — who had more than 100 RBI that season. Seaver was with us, and he helped Roger Clemens, Bruce Hurst, and everyone else. My locker was next to him, and he loved to talk. I was all ears, trying to soak it up.”

Unfortunately for the Red Sox, misfortune bit them again. Leading the series three games to two and up by two runs in the bottom of the 10th inning of Game 6 in New York, Evans recalls, “I was standing in right field in Shea Stadium. Two outs, two strikes, and I look up at the scoreboard to see, ‘Congratulations to the 1986 World Champion Boston Red Sox.’ You know what happened next.”

The Mets rallied for three runs, the last scoring when a ground ball infamously went through Buckner’s legs. In Game 7, the Mets came back from an early 3-0 deficit to win 8-5.

“For a long time, I had never looked at the film of that series,” Evans says. “But when I’d travel, someone would eventually say something like, ‘What a great World Series!’ And my reaction was, ‘What series were you watching?’ But, with some distance now, I can see that if you weren’t a fan of the Red Sox, if you didn’t have skin in the game, it was a great World Series. Still, it hurts. We were the bridesmaids again, never the bride.”

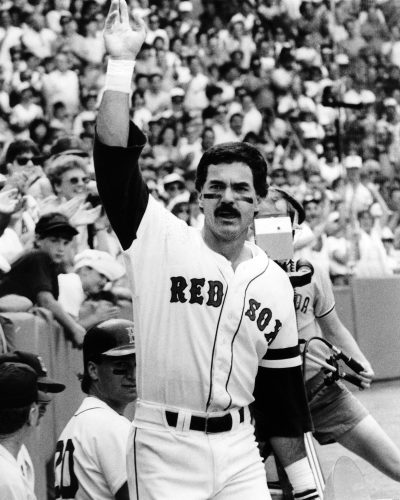

Dwight Evans waves to the crowd at Fenway Park.

(Photo by Bill Belknap/The Boston Herald)

‘Our Fight at Home’

Throughout it all, Evans played — and achieved at high levels — while dealing with the scourge of NF. His oldest child, Timothy, and youngest, Justin, were diagnosed with the condition in the 1980s (daughter Kirstin, did not develop the disorder). Evans, though, kept the diagnosis private as he and his wife worked to help their boys. How did the family do it?

“First, my wife and I are very strong in our faith as Christians,” Evans says. “That helped us put things in perspective. I played long enough, there were times I couldn’t get the job done and there would be boos. To leave the ballpark after a bad day and be in the hospital with one of my sons, I eventually understood that the fans weren’t booing me, but they were booing the situation. New England’s fans are ones that let their emotions flow, and I fell in love with it. Coming to that realization helped me separate baseball from our fight at home.”

Evans also used baseball as a refuge — something his wife couldn’t do. “When I would come from the hospital, I could drive into the lot at Fenway, and it was a free zone for me, mentally,” he says. “For the next seven or eight hours, I could separate. But as soon as I drove out of the lot, it was right back to the hospital.”

Evans continues, “My wife didn’t have a free zone. We had no family in the area. She’s so strong — almost to a fault. She helped me play as long as I did. The last eight years of my career, she’d fly out to wherever we were. She knew I missed the family.”

Justin passed away on Easter Sunday in 2019, and Timothy followed him just 10 months later. Both were in their forties. But the Evans’ family commitment to a cure continues.

“NF Northeast is where of all our money goes,” he says of the organization he and other Boston sports luminaries like former Celtic coaches Tommy Heinsohn and K.C. Jones have served. “We chose NF Northeast because we know that 90 cents of every dollar they raise goes directly to research.”

‘I Was About Winning’

Today, Evans’ biggest contribution to the Red Sox organization is as a spring training instructor, as well as a part-time ambassador during the season at Fenway Park. He’s still connected to many of his former teammates.

“Rico Petrocelli was a mentor early on for me, a great source of strength,” Evans says. “I still see Rico once a year. I talk to Yaz every other month. He’ll be 86 in August. Jimmy and I see each other a lot. He calls me 2-4 and I call him 1-4 (references to their uniform numbers).”

He says there’s still magic when you add Lynn to the mix. “We see Freddy when he comes out from California during the season,” Evans says. “The three of us always seem to gravitate when we’re together. About 15 years ago, we were doing an appearance together at Fenway, and in the room, there are pictures of one of each of us, side by side. Freddy points to the photos and says, ‘Dewey, you don’t know this, but that’s the greatest outfield of all time.’ Then he starts getting into all the stats, and it’s a good argument. We were together six years, and we were inseparable. We were really in tune with each other.”

Evans also shares his excitement about the current Red Sox — who were on a 10-game winning streak when this interview took place. “Cedanne (Rafaela) is so exciting,” he says. “He’s such a team guy. Being able to watch (Trevor) Story after all his injuries — he’s a great shortstop. Having Marcelo (Mayer) and Roman (Anthony) come up. It’s fun to watch. And (Jarren) Duran, I’m a big fan. He’s the most electric player in our system since I’ve been around. He’s thinking extra base all the time. I haven’t felt the buzz that’s been in the ballpark the past two weeks in a while.”

Evans then ties a recent moment in the ballpark back to his own early days. “When Cedanne hit that walkoff (Rafaela hit a two-run home run on July 11 to beat the Tampa Bay Rays, 5-4), they interviewed him after the game and asked how he felt. And he said, “I just want to win!” Evans recalls. “That was me — and my wife would get mad at me for not taking more credit. I’d hit a home run to win a game, and I’d just want to give credit to others. I was about winning.”

Evans pauses, then adds, “I’m very grateful for the position I was put in in life. And I think I ran the race really well.”