PUBLISHER’S NOTE: On August 24th, Massachusetts Governor Maura Healy officially announced the launch of her “MassReconnect” initiative, a $50 million program that allows Massachusetts residents ages 25 and older to enroll in community college, free of charge.

While some may be tempted to roll their eyes at a community college education, I am here to tell you our Commonwealth is home to some of the best community colleges, that create some of the most exhilarating learning experiences in the country.

In his brilliant book, DAVID & GOLIATH, Malcolm Gladwell reasons against attending a famous university just the name, theorizing that students tend to excel more as “big fish in little ponds” as opposed to“small fish in big ponds.”

This is drawn on the “Theory of Relative Deprivation” where we measure ourselves against the people immediately around us.

Often times, the same, and in some cases, better educational opportunities are in the smaller ponds.

Case in point: Bunker Hill Community College, right here in Boston. BHCC houses a program called “Compelling Conversations” which I have had the privilege of attending as a guest on a couple of occasions. Compelling Conversations brings in, well, some of the most compelling thought leaders in the world to speak to and interact with BHCC students.

On April 11th, I had the tremendous pleasure of having such a conversation with Ndaba Mandela at Bunker Hill Community College.

Ndaba is the longest serving global ambassador for UNAIDS; he is a vice president with the Pan-African Youth Parliament; and he is the co-founder and chairman of the Nelson Mandela Institute for Humanity.

Nelson Mandela is also Ndaba’s grandfather.

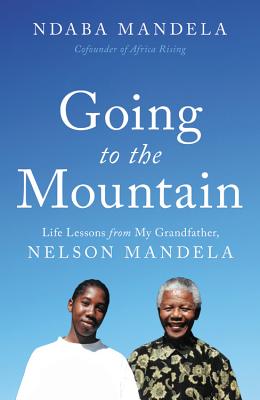

Below is an excerpt from Ndaba’s new book GOING TO THE MOUNTAIN, which a copy of was also provided for each student attending “Compelling Conversations” at Bunker Hill Community College.

I agree with Gladwell. It’s not too bad being a big fish in a little pond.

From Chapter 1 (Pages 1-14)

THE first time I met my grandfather, I was seven and he was seventy-one, already an old man in my eyes, if not in the eyes of the world. I’d heard many stories about the Old Man, of course, but I was a child, so those stories were no more real or relatable to me than the old Xhosa folk tales repeated by my great-aunts and great-uncles and other elderly people around the neighborhood.

The Story of the Child with the Star on His Forehead. The Story of the Tree That Could Not Be Grasped. The Story of Nelson Mandela and How He Was Imprisoned by White Men. The Story of the Massacre at Sharpeville. Fables and folktales drifted around in the dusty streets and got mixed in with the news on a car radio. Parables and proverbs slipped through the cracks in the Bible stories in the Temple Hall. The Story of the Workers in the Vineyard. The Story of Job and His Many Troubles.

My father grew up a hustler on the streets of Soweto, and for better or worse, a hustler is always good with a story. The Story of Where I Was Last Night. The Story of How Rich I’ll Be Someday.

Grownups all around me, each according to their own belief system, repeated their stories over and over, blowing smoke, tipping beers, shaking their heads. Talk, talk, talk. That’s all I heard when I was a child. I wasn’t really listening. I never felt those stories steal under my skin and soak into my bones, but that’s what they did.

I was a smart little boy with a quick mind and a big imagination, but I had no real understanding that my family was at the center of a global political firestorm. I didn’t know why I was always being moved from place to place or why people would either take me in or shut me out—either love me or hate me—because I am a Mandela.

I was vaguely aware that my dad’s father was a very important man on the radio and TV, but I couldn’t begin to know how important he would become in my own life or how important I already was to him. I was told that he loved my father and me and all his children and grandchildren, but I had seen no evidence of that, and I certainly didn’t understand that there were people who thought they could use Madiba’s love for us to bloody his spirit and bring him low.

They thought the weight of his love might break him in a way that hammering rocks in the heat of the South African sun could not. They were mistaken, but they kept trying.

First they let a large group of family members visit for his seventy-first birthday in July 1989. That must have been like a drop of water on the tongue of a man who’s been dying of thirst for twenty-seven years, but Madiba still refused to yield any political ground, so six months later, they allowed a holiday visit on New Year’s Day 1990, just a few weeks after my seventh birthday.

My father invested no drama in the announcement. He simply said, “We’re going to see your grandfather in jail.” Until that moment, such a suggestion was like saying we were hopping in the car to go meet Michael Jackson or Jesus Christ.

People on TV seemed to believe that my grandfather was a bit of both: celebrity and deity. This turn of events was quite unexpected, but in African culture, children don’t ask questions. My father and grandmother said, “We’re going.” So we went. No further explanation was offered or expected, but I was burning with curiosity.

What would jail be like? Would Grandmother Evelyn lead us through the iron bars and down a cement hallway to a razor-wired yard? Would heavy iron doors clang shut behind us—and would someone remember to come back and let us out? Would we be surrounded by murderers and thugs? Would my aunts beat them off with their enormous purses?

I was ready to fight, if necessary, to defend my family and myself. I was good with a stick. My friends and I had sharpened our stick-fighting skills through years of pretend fights in the dirt streets and trampled yards. I rather enjoyed daydreaming about a great battle in which I would be a hero, and there was plenty of time for daydreaming as we made the thirteen-hour drive from Johannesburg to Victor Verster Prison in a caravan of five mud-encrusted cars loaded with Mandela wives, children, sisters, brothers, cousins, aunts, uncles, babies, and old folks.

So you can imagine, it was a pretty long trip. We drove for what seemed like an eternity, through rolling hills and across expansive savannahs to the Hawequas Mountains. We turned south from Paarl, a little town full of Dutch Cape houses with scrolled white facades. Sitting in the back seat, I rolled down the window and inhaled the clean scent of wet grape leaves and freshly tilled soil.

For a thousand years before the Dutch East India Company came to this region in the 1650s, it was the land of the Khoikhoi people, who herded cattle and had great wealth. Now vineyards dominated the landscape, and the mountain called Tortoise by the Khoikhoi had been renamed Pearl by the Dutch.

The mountain knew nothing of this, of course, and as a seven-year-old boy, I was equally oblivious. I saw only the vineyards, verdant green and rigidly in order, and I accepted without thinking twice that this was as it should be. I never questioned it, because as an African child, I was taught not to ask questions, but now, as a man—as a Xhosa man—as an African father and son and grandson, I do wonder: At what point do the roots of a vineyard sink so deep that they become more “indigenous” than five hundred generations of cattle?

This sort of question is my grandfather’s voice in my head, even though it’s been a few years since his death and many more years since I went to live with him in a rapidly spinning world where we broke and rebuilt each other’s idea of what a man is.

His voice still rumbles through my bones, bumping into the old stories. It has settled into the marrow, like sediment in a river. As I get older, I hear his voice coming from my own throat.

Everyone tells me I sound like him, and knowing that I do makes me weigh my words a little more carefully, particularly in a public setting.

At the prison entrance, there was a small guard shack with a swing arm gate behind a white angled arch. A bright green sign with yellow lettering said: VICTOR VERSTER CORRECTIONAL SERVICES. Beneath this was inscribed: Ons dien met trots. (“We serve with pride.”)

It’s possible that my aunts exchanged glances at the irony of that, but if they did, I didn’t notice. I was staring up at the towering rocky faces of the mountains. Grownups chatted with the guards who leaned from the window of the guard shack. Talk, talk, talk.

The guards hustled the two dozen Mandelas out of the five cars and into a large white van. Packed tightly on the hard bench seats, we were rolling again, but we didn’t go to the big prison building with its high walls and coiled razor wire. We turned down a long dirt road, little more than a worn set of parallel tire tracks that led to the far, far back corner of the prison complex. The van pulled to a stop outside an arched garage door, and we all got out in front of an attractive salmon-colored bungalow shaded by fir and palm trees.

My grandmother and great-aunts were dressed up as if they were going to church or a special social event, so they stood out like exotic birds, all bold prints and bright colors, against the pale pinkish walls. My father and the other men present wore dress shirts and ties, and before they approached the gate, they shook their carefully folded suit coats and put them on.

The house was surrounded by a decorative garden wall that was not even as tall as my father. Two armed guards stood outside a little wrought iron gate—like a pretty little garden gate, not the dramatically clanging iron doors I’d imagined—and they greeted us and waved us inside.

And there was my grandfather. I barely glimpsed his broad smile before he was engulfed in a wave of affection. The women were crying as they rushed to throw their arms around him, crying, “Tata! Tata!” which means “father.” The men maintained stiff chins and straight postures, each waiting his turn to embrace the Old Man firmly, to grasp his hand and squeeze his shoulder.

No tears, no tears. Only those firm jaws and hardy handshakes. The children, including my brother Mandla, my cousin Kweku, and me, hung back, not quite knowing what to expect. To us, the Old Man was a stranger, and he seemed to understand this, smiling at us over the heads of our parents and grandparents, patient but eager to get to us and greet each one of us individually.

When it was my turn, he took my small hand in his huge, warm grip.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

“Ndaba,” I said.

“Yes! Ndaba! Good, good.”

He nodded enthusiastically, as if he recognized me.

“And how old are you, Ndaba?”

“Seven.”

“Good. Good. What grade are you in? Do you do well in school?”

I shrugged and looked at the floor.

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” he asked.

I had no answer for that question, being a child who’d been shuffled from here to there. I had seen very little beyond the poverty and obstacles that surrounded me in the inner city, and I didn’t want to embarrass myself by saying something dumb like “stick fighter.”

The Old Man set his big hand on top of my head and smiled.

“Ndaba. Good.”

He shook my hand again, very formal, very proper, and went on to greet the next child in line. The moment, I’m sorry to tell you, was not at all momentous.

Sitting here now, trying very hard to remember the feeling—his hand on my head, that gigantic handshake, the towering height of his pant leg, the smell of linen and coffee when he bent down to hear my shy answers to his questions—nope. I got nothing. All of that was lost on me then.

I’ve read what my grandfather wrote about it in Long Walk to Freedom. He was always reluctant to write about personal family matters, but he describes the house at Victor Verster as “a cottage” that was “sparsely but comfortably furnished.”

That made me laugh out loud when I read it, because to me as a kid from Soweto, this place seemed like a mansion. The overstuffed sofa and matching easy chairs were like rose-colored clouds. The impeccably clean bathroom was the same size as the bedroom I shared with my cousins.

A white man whose job was to cook and keep house for my grandfather came and went from the kitchen, trotting out a parade of platters and bowls and baskets of dinner rolls.

Out back, there was a pristine blue swimming pool that made my skin itch to dive in. The pool was flanked by potted plants and surrounded by the garden wall.

My grandfather told me later that the garden wall was topped by razor wire, but I was either too short to see that or too busy playing on the impossibly green grass. I couldn’t have been more impressed if we’d found the Old Man locked up in the Ritz Hotel.

The next time somebody asked me, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” I said, “I want to be in jail!” Of course, the prison I expected to see that day was Robben Island, the stark hellhole where my grandfather had spent a large part of his life.

As anti-apartheid sentiment grew around the world, the powers that be had Madiba moved to the house at Victor Verster in an effort to separate him from his friends and drive a wedge between the members of the African National Congress. His political foes hoped to chip away at his resolve with the seductive comfort of this pleasant little home and the promise that he could see his family: the wife who’d been imprisoned and tortured, the children he hadn’t seen since they were small, the grandchildren he’d never seen at all.

But his foes underestimated him. For two years, he maintained his resolve and held his ground in round after round of bitter argument over the future of South Africa.

It would be a long time before I fully understood that my cousins and I were lolling that day with our feet up on the chairs where my grandfather routinely sat with powerful heads of state, embroiled in political and ideological debates that would soon alter the course of history.

As the day wore on, the grownups gathered in the kitchen and dining room, as grownups tend to do, and the kids flopped down on the carpet in the living room and popped a video tape of The NeverEnding Story into the VCR.

I vaguely remember the adult voices rising and falling through laughter and lively conversation with my grandfather’s resonant bass at the center of it all, but we had no interest in their conversation. To be totally honest,

I have to admit that my memory of that first meeting with my grandfather is quite hazy. I know what he was like that day mainly because I spent thousands of other days with him as I grew up and he grew old.

For the exact details, I have to rely on what I’ve seen more recently about the place that’s now called Drakenstein Correctional Centre. The bright green and yellow sign is still there, but people only see it because they’re visiting the statue of my grandfather as a free man, bronze fist held high, striding out of Victor Verster on February 11, 1990.

In my mind, the particulars of that family visit are a collage of recollection, newspaper clippings, and conversations with my grandfather, grandmother, Mama Winnie, and other old folks who were there.

But I do remember one thing very clearly: The NeverEnding Story. I suppose a Xhosa storyteller might call it “The Story of the Boy Who Saved the World from Nothing.”

In it (for those of you who have not seen this movie or read the book by Michael Ende), a boy goes on a perilous journey to overcome an invisible menace, The Nothing, which is slowly, steadily swallowing everything and everyone in the world. The daunting challenge facing the boy is that he must find a way to stop this invisible menace, but first, he must convince others that it exists. He must somehow win them over to the understanding that all those who have vanished had value and that the world now perceived as “normal” is not the world as it should be—and that the world must change in order to survive.

In a very real sense, that is the story of my grandfather, Nelson Mandela. I believe it is also my story.

And I hope to convince you that it is your story as well. Madiba and his colleagues in the African National Congress, Gandhi and his followers, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and all who marched alongside him—these people successfully broke the physical chains that existed under apartheid in South Africa, British rule in India, and Jim Crow segregation in the United States.

The wrongheadedness and evil of apartheid and segregation were very clear. Black people were told, “No, you can’t live in such and such a neighborhood or this or that house, because that’s too close to the white people. No, you can’t get on that bus. No, you can’t use that tap or that toilet.” These laws were wrong, and the judges, police, and prison guards were wrong to uphold them. If they truly did “serve with pride,” certainly, they should look back with shame.

Any law that violates the civil or human rights of another person should offend our natural sense of social justice. It should grind like sandpaper on our conscience, and I think it does, but we get very good at ignoring it.

“To be free is not only to cast off one’s chains,” my grandfather said. “It’s to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

When my grandfather and so many others fought for civil rights around the world and broke free from those physical chains of apartheid and segregation, it was very easy to identify who the enemy was.

But in today’s world, there is a new fight for young Africans—and for many young people around the world—and that is to break the mental chains that still exist. It’s a lot harder to break the mental chains because you cannot touch them. They’re not tangible. You cannot point them out. These chains exist within your mind, but they can be stronger than iron. Every link is forged by an act of injustice, large or small. Some are inflicted by the world; others we inflict on ourselves.

Bob Marley sings about mental chains in “Redemption Song” and reminds you that the only one who can emancipate you is yourself.

As I travel the world, I hear young brothers and sisters talk about the “American dream”—a big house with a swimming pool and posh furniture and a servant—and I recognize that place as a jail.

I hear talk, talk, talk on adverts and reality TV shows, nattering constantly about that narrow vision of worth and wealth, and I can’t help but contrast that with the young African in Monrovia whose dream is to have a library, or the child in Syria whose dream is to go to a school with a roof, or the young black man in the United States who’s attacked for simply saying, “My life matters.”

In them and in you—and in myself, because my grandfather opened my eyes to it—I see the new generation who will rewrite the world. “Sometimes it falls on a generation to be great,” Madiba said. “You can be that great generation. Let your greatness blossom.”