Somerset artist Brian Fox’s work has become synonymous with New England’s sports success and celebrity culture. In the midst a life-changing, multi-painting Vietnam veteran project, the scope of his work continues to grow.

“I liked sports, and I liked to draw — like everybody did — when I was a kid. I was certainly no kind of athlete who’d play at any sort of high level, but I liked sports and I think that’s what pushed me in the direction of sports art,” says Brian Fox, the Somerset, Mass.-based artist known for his paintings of athletes, celebrities, and more. “This was one of the things I liked to do, and found myself pretty good at, when I was a kid. My parents encouraged me. My friends always came to me to draw things. You go where you’re encouraged.”

Fox grew up in Somerset and — now married with two sons, one a freshman in college, the other a junior in high school — lives in a home in the same neighborhood today. His early career was checkered, though, as he found his way to his eventual passion and success. A degree in fine arts from UMass-Dartmouth was followed by a string of jobs as an illustrator and artist that, while they paid, didn’t completely fulfill.

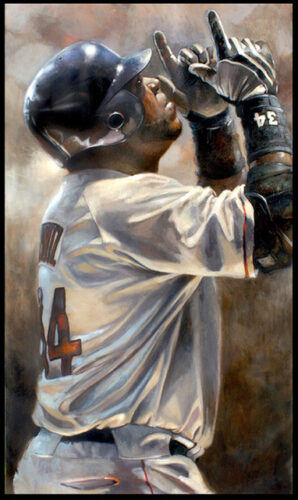

The big break for Fox came in conjunction with one of the region’s most memorable moments: the Red Sox winning the 2004 World Series. Soon thereafter, Fox created a painting of pitcher Curt Schilling (he of the legendary “bloody sock” performance in Game 6 of the 2004 American League Championship Series against the New York Yankees) for the ALS Association. The work sold and the proceeds went to the charity — “I was paid nothing, other than for my supplies,” Fox says — but the painting sent Fox down the path to where he is today.

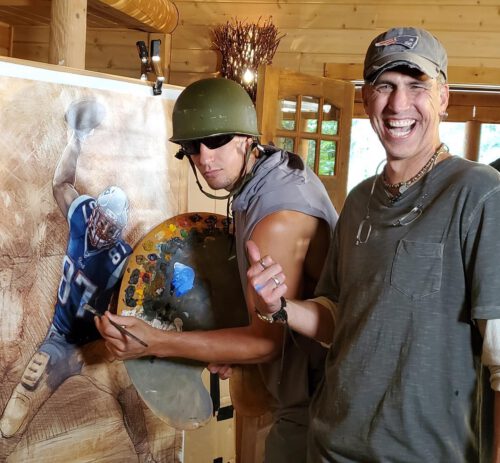

He’s created memorable images of legends like Jackie Robinson, Keith Richards, Jim Morrison, Tom Brady, and Muhammad Ali. At the same time, he’s a relationship builder, which is one of the reasons his success has been so vast.

Fox has forged relationships with athletes and organizations such as Schilling, Josh Beckett, the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA), the National Hockey League (NHL), Rachel Robinson and more, while raising money for their favorite charitable organizations, including the ALS Association, Major League Baseball Players Trust, Josh Beckett Foundation, Providence College, Hockey Fights Cancer, and the Jackie Robinson Foundation.

He served as the commemorative artist for the MLB All-Star Game in 2007, 2008, and 2009 and was the official sketch artist for the 2007 World Series (another Sox triumph). He also created artwork for the program covers for the 2010 and 2011 Bridgestone NHL Winter Classic events, played outdoors on Jan. 1 of those respective years.

His client base also includes (or has included) Disney, the National Football League (NFL), Foxwoods Resort Casino, and both Caesars Palace and the Mirage in Las Vegas. His work for Disney includes being one of the company’s official canvas oil painters for its theme parks and cruise lines.

And there’s so much more. I spoke via Zoom with Fox on May 2 from his studio on the South Shore. The following conversation is lightly edited for clarity and space considerations.

BostonMan: Growing up, what prompted your interest in art and when did you decide to make painting your life’s work?

Brian Fox: I’m the first person to go to college in my family. My parents saw my interest in art and said, “You’re going to go to school for art.” I didn’t know what that meant, but we found a local school down here (UMass-Dartmouth), and I went to art school. My dad was a musician, and my parents were younger when they had me, so they kind of nudged me into going to school. Not that they knew what was going to come of it!

I went to school for illustration. You’re taking on assignments, and you’re learning a bit of the business side of it. After college, I went to work for a local magazine as the on-staff illustrator. It went under about seven years later, and I went to work for a newspaper, designing ads. I hated the job, but there’s no tougher deadline than a daily deadline, so you learn a lot. You’re dealing with clients, with salesmen. All these things help create people skills that, a lot of times, artists are not required to have.

From there, I went to work for a company called Liquid Blue, a multimillion-dollar t-shirt company in Rhode Island. I worked there for seven years. It was all merchandise: Grateful Dead, rock-and-roll stuff, sports-related stuff. I was able to design t-shirts all day long, with a salary and benefits. I was working with six or seven other artists; it was a cool job. Again, that’s how I got my chops in meeting deadlines, dealing with a boss, how to change my artwork. You develop a thicker skin when you’re dealing with bosses and people telling you to make changes.

Toward the end of my time there, the boss and I had a parting of ways. I took a leap of faith and quit the job. My wife was on board, but I didn’t know exactly what I was going to do. I had one kid, one on the way, a mortgage, car payments. People thought I was crazy, but I just felt like I had to go in another direction.

I had no plan on going to where I am now. It was years before I really made any money. My wife was a CPA and had a steady gig, luckily for us.

BostonMan: What do you consider your first professional success as a painter and how did it change things for you?

Fox: The year I quit was the year the Red Sox ended up winning it all in 2004. After they won, and Curt (Schilling) had the “bloody sock” game against the Yankees, I pitched them the idea of doing a painting of Curt. I thought maybe they could use it to raise money for the ALS Association, which he championed at the time. And that was it: I got swept up in the Red Sox mania in 2004 because I did a painting of the best pitcher on the planet at the time and gave it to charity.

It sold for thousands of dollars. When I got home, I got called a fool for giving it away. But when you go to this event, and there are ALS patients there, your eyes get opened very quickly, because as much as I’m struggling to pay the bills and take care of my kids, there are people in wheelchairs, who can’t move their hands or their feet, and are blowing into a tube to get around in a wheelchair. You’re changed when you see how much need other people have.

Because it was the Red Sox and Schilling, the story of the painting caught fire in the media. They became more interested in what I was doing, and then I started to make some inroads with other athletes and celebrities. I started getting invites: “Hey, why don’t you come to the All-Star Game and paint live here?”

And the Patriots were rising, too. I got to know some of the players. I really got hooked in with these athletes because the Boston sports scene was ravenous and growing quickly. I happened to just be riding that wave with them.

BostonMan: What is it about sports and athletes that draws you to them as subjects?

Fox: Different sports bring different kinds of action to what you’re trying to capture on the canvas. On top of that, you want to try to capture the portrait of the player as well. They have this incredible energy. When you start to pay attention and study these guys, they make it look easy because they’re talented, but they work so hard. They put so much time and energy into this, and you must respect what they put into things. Maybe if you know the personality, the pose is different. Maybe it’s before the windup; or some of these guys play with such an intensity, maybe the painting is more about the face. Sometimes it’s the opposite: some of these guys are so graceful, you want to capture that.

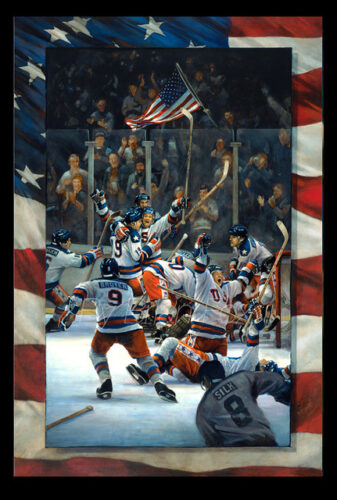

BostonMan: How did the 2010 partnership with Jim Craig celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Miracle on Ice come about?

Fox: Jim has become another friend. One of the coolest things about the job I have is that, many times, you develop friendships with these guys. For this, one of my collectors had an event set up for the 1980 U.S. Olympic hockey team to sign my painting. It was a couple towns over, so I asked if I could go. I went, and about halfway through the event, I think most of the guys just thought I was working for the memorabilia company. But I was talking to Jim and told him I was the artist, so we started to talk a little bit.

From there, I did a painting of him, with the flag wrapped around him after they’d won and he’s looking for his father. When I did that painting — again for the same collector — I’d just gotten to know him, and I’d stop by to talk, which led to us having some incredible behind-the-scenes conversations.

He’s talking about looking for his father in the stands — and we all remember that image — but what he told me was that his mother had died of cancer not long before that and he was missing her. At the same time, he was looking for his father. He’s just a kid looking for his parents. As an artist — as a person — you can imagine that, and now I’m trying to capture it for the canvas.

BostonMan: How did you get involved in painting horse racing? What’s your favorite work in the sport?

Fox: When I got started doing this in 2004, I just threw a whole bunch of sh*t against the wall every day. I was trying to bring in money for the house, pay the bills, you know? I had a friend up in Saratoga, N.Y., which is about a four-hour drive from me, who said you should come up here and start painting horses.

So, I started to go up during race season, set up in different restaurants, and paint live. Slowly but surely, I started to meet people in this community that owned horses. It took years, though. At first, I’d go up and paint live and maybe sell a poster. You’d go up and spend all this time and money, and then come home with $100. It was very disheartening at times.

The more I did the horses, though, galleries started coming around and showcasing my work. Restaurants would put up paintings I’d done. Owners would see them, and say, hey, we want a painting of a horse. Once I started working for one owner, that gave me credibility with the other owners.

BostonMan: What’s your favorite work in the sport?

Fox: I loved doing the American Pharoah work. A Triple Crown winner, something we’ve seen a couple times now, but before him, there was such drought (before American Pharoah’s 2015 triumph, the previous horse to accomplish the feat was Affirmed in 1978). I’ve also worked for the Jackson family of Stonestreet Farms and the Kendall-Jackson winery. They had many horses that were Hall-of-Fame-level horses, like Curlin. Horses are just incredible to paint. I got access to the stables with Stonestreet, and as an artist it’s amazing to be up close with those animals.

BostonMan: You’ve also done celebrity work — particularly musicians. What do you like about creating art of those who are artists themselves?

Fox: It’s a slightly different thing. I grew up in a rock-and-roll household. My dad was always playing with a band in the garage. There’s a different level of energy and excitement these guys bring when they’re performing on stage that you try to capture on canvas. And, you know, I’m just a fan of the music. I want to paint what I want to put on my own walls at home.

So, I start working with the Patriots and Red Sox, and the musicians and actors are fans — so by association, my name got kicked around these circles that cross each other. Wahlberg is a big Patriots fan, he’s at the games, and then the Patriots are at his premiere. I start to run into them. Or I go to Rob Gronkowski’s house, and Mark is there. They see you in these trusted circles, you don’t betray that trust, and they start to trust you. They may want something for themselves, a gift for their wife, or something for their charity. It takes a long time, but once you’re trusted both personally and with the quality of your work, then it kicks in.

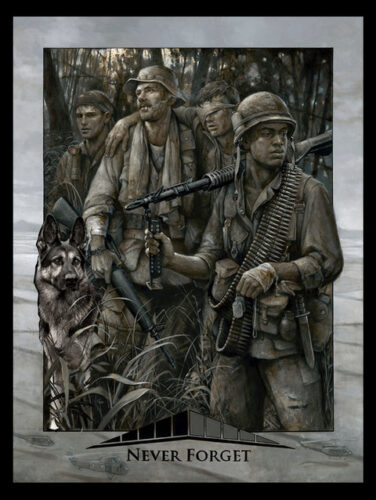

BostonMan: Last year, you created a piece called “Never Forget” for the launch of Fall River’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall. How did that project start and what does it mean to you now?

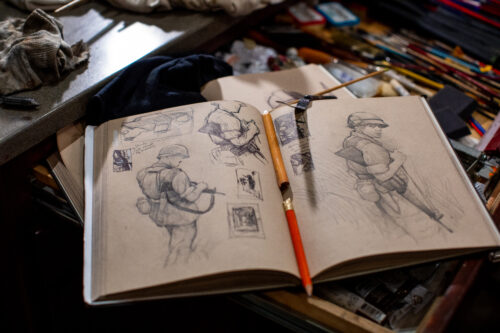

Fox: The folks behind it came to me and said, “We’re trying to raise money, and we want to do it in a creative way. We’ve seen how you’ve been able to do it with athletes. Can you do something for our project?” The project was a memorial wall, much like the one in Washington, D.C., but here in southern New England. They thought by doing this painting, I could help raise both awareness and money. My only request to them was to see if they could put together a group of six or seven in-country Vietnam veterans to visit me in the studio. I just needed to know what’s important to them; I needed them to be comfortable enough to be able to talk to me and share something.

I connected with this group of guys, and they’d come into the studio. It was a private setting — I did film it with their okay — but essentially what they said to me was, “We never want to forget the guys who didn’t come back.” They were incredibly serious about it, and this is where things changed for me.

One of the vets, his name’s Harry Terrien. He’s a lawyer now, and he’s done well in life. But when they brought him in, they told me he’s never talked about the war. He’s served two tours as a Marine, he saw it all, and now he’s on the committee. About halfway through the conversation in the studio, he starts talking — and everyone else in the room shuts up. You realize immediately how much respect they have for this gentleman. What he started telling us, you’re just blown away by.

What I thought was going to take me a month to paint took six months to get right. The response to it was overwhelming: I had guys come in who broke down and cried. I’m talking Special Forces guys. This more powerful than I ever thought, and it’s not just because of the painting. Nobody’s done a lot for these guys. It meant so much to them that somebody took the time to do something meaningful for them. And it happened to be a painting.

We unveiled it (the event took place at Veterans Memorial Bicentennial Park in Fall River on May 15, 2021) and the emotional response again blew me away — so much so that I thought, “One painting is not enough.” I’m not getting paid for it, and my manager will kill me because it’s bad business. But God put it on my heart, and I have to do more. So, I’ve taken it on: five massive paintings to continue the narrative of this story. I asked the vets to come back and help me again, and they have. Normally I don’t let anyone into my studio, but the Vietnam vets are always welcome.

And I’ve even let them paint on the paintings a little — that’s not something I do very often. One vet told me after I’d let another vet paint, “Brian, that paintbrush is connected to his soul.” You hear that and see that; you start to realize you can help somebody. We’re not given our gifts to hoard them.

BostonMan: When you think about the people who have bought your work, what does it mean to you?

Fox: It’s two things: surreal and humbling. It’s surreal because you look at the names, and you grew up watching them play on stage or on the field. You never think you’ll be in the same circle with these guys, but then they become not only collectors of your work but also friends. It’s incredibly humbling because I know how talented these guys are, and for them to be collectors of my stuff, it’s a seal of approval.

BostonMan: Which of the people that own a painting of yours really makes you think, “Wow!”?

Fox: Steven Tyler is one. Tom Brady and Gisele own a few, and Jack Nicklaus, now. It’s crazy. I have to tell this story: a while back, I was over at Steven Tyler’s house one morning, and we were just hanging out. He’s in a terrycloth robe, he’s got his rings on, his hair’s up. He’s a rock god, right? As I’m driving home after hanging out for a couple hours, I start thinking “What would he look like if he was an animal or a character?” He’s such a larger-than-life guy. A lion, a tiger … a werewolf!

I was so burnt out on some of my other stuff, I got into doing this werewolf series, inspired by him. And it took off, almost bigger than anything. He owns one, Gronkowski owns one, it’s incredible. Now, I’ve done more than 30 paintings of this werewolf, and the celebrities are collecting them.

BostonMan: What did it mean to you to be named the U.S. Sports Academy’s Sports Artist of the Year in 2020?

Fox: Years ago, when I first quit my job, I knew that this group existed, and they’d give out this award. I tried to get on their radar for probably five years, but never heard anything back. I completely lost interest in trying to get on their radar. Big names have won this award — LeRoy Neiman. Then, 10 years later, I get a call — I thought it was a joke — “You’ve won Sports Artist of the Year.” It was an incredible honor to be put up with the other artists who’ve won the award. It’s like getting an Academy Award in my field.

BostonMan: Of the relationships you’ve forged through your work, what’s the most memorable for you and why?

Fox: There are a lot, but Matt Light from the New England Patriots has become the strongest friendship. He’s a dear friend. He helped me find a surgeon when I had cancer. The projects he and I come up with, he’s just got great vision well beyond the field. It’s been fun to work with him on so many different levels.

And then there’s the Vietnam project. From a project level, it has probably moved me the most. But all these other side projects all come from the sports world. Even working with Steven Tyler and Mark Wahlberg, all of it stemmed from the sports platform I created. The ripple in the pond started with the sports work.

BostonMan: What do you consider your best work, and why?

Fox: I don’t have an answer because I’m constantly driven to do more. I always feel like I can do better. The Vietnam project has a lot of meaning to it; it’s changed me over the past few years, but I’m always looking to improve. You know, I’ve blowtorched six-foot paintings I’ve worked on for a year (laughs). I like pieces of my paintings, but I don’t think I’ve gotten to that “this is my best” point yet — and I don’t think I ever will.