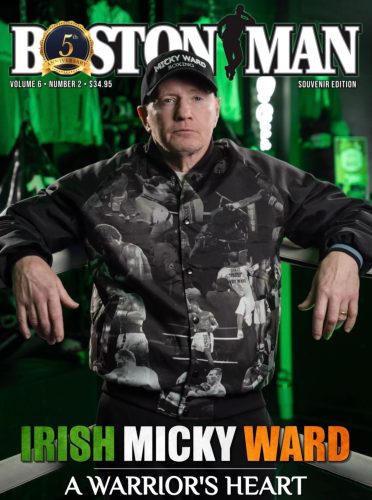

He is The Pride of Lowell, but in many ways, also The Pride of America.

Representing an old-school blue collar work ethic, with an integrity and

honesty that humbles us all, Irish Micky Ward continues to embody the

same spirit and drive that captured our imagination twenty years ago.

THERE is that distinct feeling of being in a boxing gym.

It is said you can learn more about yourself, your mettle, your limitations -your mortality- inside the confines of a boxing ring than you can in any other arena.

Men are hardened, brotherhoods forged, lifetime bonds are made and disciplines are learned; all inside the walls of a boxing gym; and more specifically in between the ropes of that ring.

With the emergence of ‘boxing’ as a trendy fitness class in the 21st century -and the evolution of modern training and facilities- the present day boxing gym is certainly a little different than the ones that preceded it in past generations.

Yet, the soul of the boxing gym -the sounds of gloves hitting mitts, the rattling of chains on a heavy bag, the ringing of a bell to signify rounds, the “tat, tat, tat” of jump ropes whipping the floor- all remain the same.

ON this early February morning, Danny Direct and I are heading out to a small boxing gym in rural Westford, MA, about 35 miles north of Boston.

This is no ordinary gym, however. And this is no ordinary occasion we are setting out to.

As we pull up, we are greeted by the man that has brought us out to his gym today, albeit not for a workout. On this day we are shooting the cover of the magazine you are now reading.

“Welcome boys,” Irish Micky Ward, the Pride of Lowell says to us as he opens the front door of Box to Burn, the training facility he co-owns with his nephew and godson, Sean Eklund. “Are you ready to get started?”

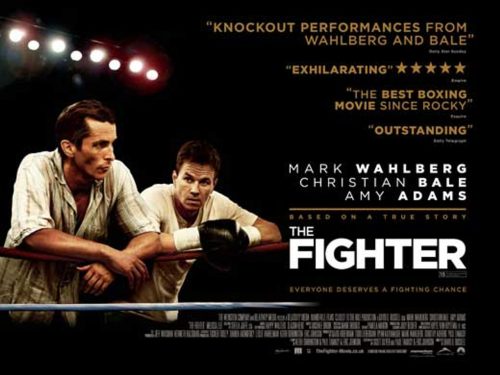

It’s been over twenty years since Micky Ward last laced up his gloves, his final bout coming on June 7th, 2003 in Atlantic City’s Boardwalk Hall. That fight marked the final chapter in his storied career -a career that in 2010 was brought to the big screen with Mark Wahlberg portraying Micky and Christian Bale, his brother Dickie (Dicky in movie) Eklund, in the blockbuster film The Fighter.

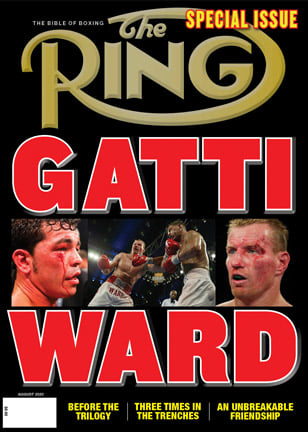

That fight also marked the final chapter in an epic trilogy he co-authored with his one-time rival, turned friend, turned brother: Arturo Gatti. A trilogy that is cemented as the greatest in the history of prizefighting, with the ninth round of their first bout widely regarded as the greatest single round the sport has ever seen.

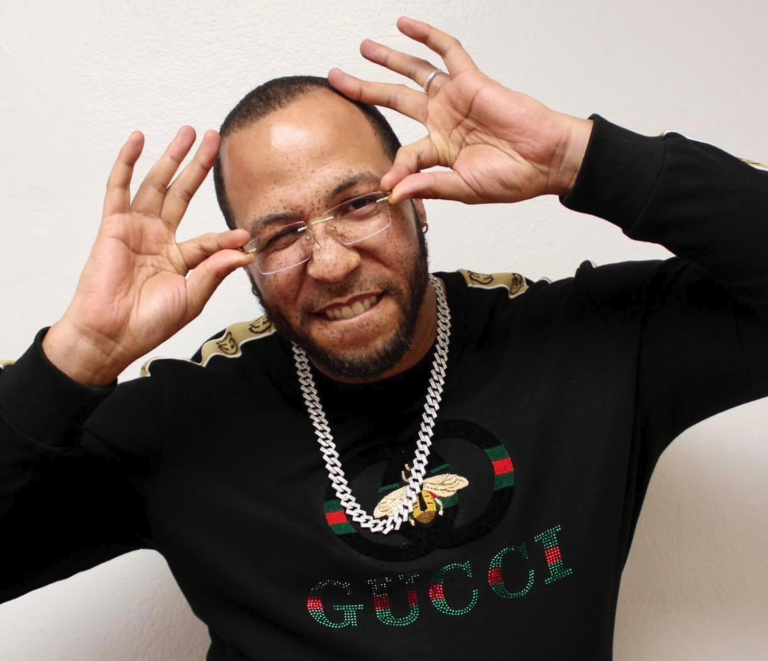

With rumors flying of a Fighter 2 sequel (which would depict the Gatti trilogy); new releases launching from his Team Micky Ward Apparel line; new events planned with his Team Micky Ward Charities Foundation; and his partnership with Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy (to learn more regarding traumas of CTE); The Pride of Lowell is showing no signs of slowing down any time soon.

And for a man who solidified a reputation of ‘always moving forward’ inside the ring -with a blue collar lunch pail work ethic and mentality- why would we expect anything different from Micky Ward outside the ring in retirement?

CHAPTER 1 – A Kid From Lowell

GEORGE Michael Ward, Jr was born on October 4th, 1965 in the mill town of Lowell, MA, where along with older brother Dickie, grew up sharing a household with seven sisters, a mixture of Wards and Eklunds.

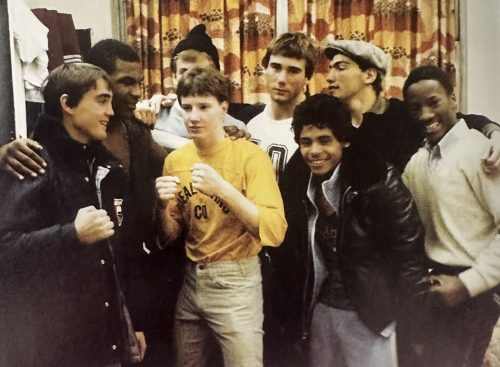

Raised by his parents, George M. Ward Sr, and Alice S. Eklund-Ward, “Micky” as George Jr was nicknamed by his family at an early age, enjoyed a typical Generation X childhood.

“It was great growing up,” Ward remembered. “Lowell was a little different in the 70’s then it is now, a little grittier, but we were never really bothered by it. There was always things to do, friends to hang out with.”

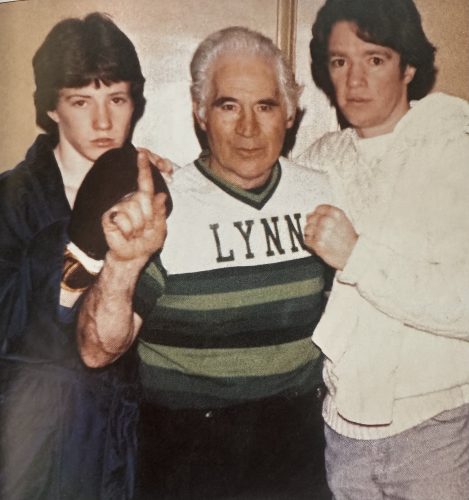

Like most kids in his neighborhood, sports were a dominant part of his early life. By age seven, he was regularly going to the gym with Eklund, eight years his elder, but unlike his older brother, boxing was not the first or only competition he was passionate about.

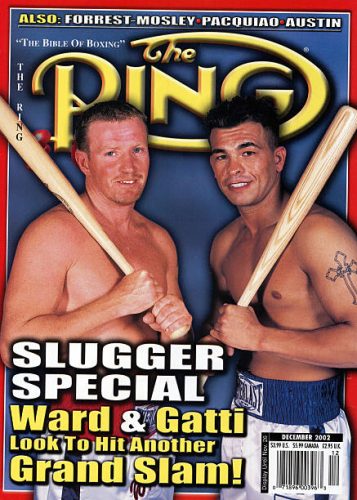

“I played all sports when I was younger,” stated Ward. “I really loved baseball. I played on a lot of different teams from little league through high school. I’m happy things turned out the way they did with boxing, but baseball is the other sport I really enjoyed.”

Ward also earned a reputation as a formidable free safety on the gridiron and established himself as a worthy wrestler on the mats, even winning a Lowell city tournament in junior high school.

But it was boxing, of course, that was in the familial DNA.

In 1972, at age seven, Ward competed in his first amateur bout at the old Lynn Harbor House, in Lynn, MA. His opponent that afternoon -also from a famous Massachusetts boxing family- was Joey Roach, brother of HOF trainer Freddie Roach, and father of Punch 4 Parkinsons founder Ryan Roach.

Both young boxers came in at fifty pounds for the match, but Ward was giving up two years in age to his older opponent.

“I was nervous,” admitted Ward. “But it wasn’t so much about fighting Joey, I was more nervous during the weigh-in.”

Charles “Skeets” Scioli, one of the pioneers and most influential figures in New England amateur boxing was the promoter of the card, and when he pointed his finger and barked to “get on the scale!” it made youth fighters within ear shot stand alert.

“He was a scary guy to us kids,” Ward laughed at the memory. “I was maybe 4’1 at the time and he was probably 4’10. He had this raspy voice. I can still it hear it in my head today.”

The actual fight lasted two rounds and was ruled a draw before being cut short due to rain. Both Ward and Roach received a trophy for their efforts, and afterwards everyone gathered in the downstairs reception area of the Harbor House to enjoy refreshments and a live blues and funk band.

“That’s still my favorite genre of music,” Ward said grinning. “It’s all I listen to today.”

Following his amateur debut, Ward continued to fight in local sports shows and small tournaments.

“It wasn’t anything too crazy,” he said. “Mostly three round exhibitions. Both kids would receive a trophy at the end.”

Then, in 1977, at the age of eleven he entered and advanced to the finals of the New England Junior Olympics, before dropping a close decision to a fighter from Lynn in the championship.

The next year, he returned and this time won the New England Juniors before later that summer sitting ringside for his brother’s most famous fight, a ten round contest against Sugar Ray Leonard at the Hynes Convention Center in Boston.

“It cracks me up when I watch highlights from that fight and can see 12-year old me right there in the front row,” Ward said.

Eklund would take Leonard the distance, ultimately dropping a unanimous decision, but in the ninth round -and what has become one of the most famous barroom discussions in local puglist lore- he either knocked down or pushed/slipped Leonard to the canvas. The official ruling was a slip, but the debate among boxing afficionados lives on to this day.

With brother Dickie by his side, Ward continued to improve and climb up the amateur rankings.

In 1978, he participated in and lost in the finals of the 70-pound division of the super competitive Silver Mittens tournament in Lowell.

In 1979, Ward again placed runner-up at Silver Mittens, this time in the 80-pound weight class.

And then, in 1980, he finally got over the hump, capturing gold in the 90-pound division at Silver Mittens.

By now, Ward was beginning to emerge as a top amateur talent, establishing himself as more than just “Dickie Eklund’s little brother.”

In 1983, he fought and won the New England AAU tournament (now called the ABF tournament), earning a trip to Lake Placid, New York for the regional finals. There, he met and befriended a 16-year old phenom, Mike Tyson, who was competing in the tournament’s heavyweight division.

“Mike was fighting at 200 pounds and I was 139,” Ward recalled. “Even back then, he was built and punched with a grown man’s power. We each won our weight class and went out to Colorado Springs together for the nationals. We hit it off at that tournament and remain good friends to this day.”

CHAPTER 2 – Turning Pro

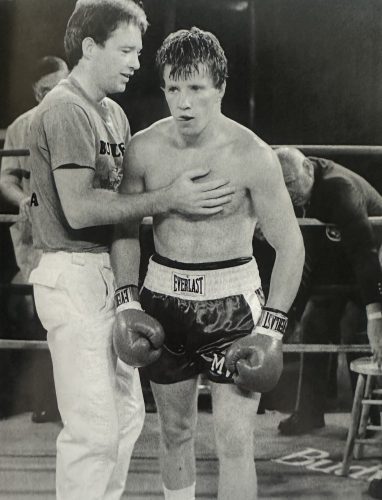

BY 1985, there wasn’t a whole lot left for Ward to do in the amateur ranks, and on June 13th of that year, at age 19, he made his professional debut at the Roll-on-America skating rink in Lawrence against a fighter named David Morin.

Eklund and his trainer, Johnny Dunn, oversaw Ward’s camp and preparation for his pro debut, but come fight night Dickie was nowhere to be found.

“He was hiding somewhere,” Ward said smirking. “But I was fine, Dickie did a great job with the camp, and Johnny was an excellent trainer. I was totally prepared and ready to go.”

And it showed in the ring. Ward made fast work of Morin, stopping him in the first round, and just like that his professional career was off and running.

Two months later, Ward picked up another TKO, this one at the Lowell Auditorium. Feeling fresh and unscathed from the fight, he looked to pick up another quick bout, applying to be on a card in boxing hotbed Atlantic City, NJ, a few days later.

New Jersey Athletic Commission rules state that fighters must wait a mandatory two weeks in between bouts, and when filing the paperwork to be on the Atlantic City card, Ward’s team bumped up the date of his last fight in order to fall into the criteria of this mandate.

However, NJ Athletic Commissioner, and former linear heavyweight champion, “Jersey” Joe Walcott caught the oversight and suspended Ward from fighting in New Jersey “indefinitely.”

“That was a terrible sinking feeling,” Ward said of the suspension. “At the time, Atlantic City was one of the top spots a young prospect wanted to be, and they wouldn’t even say how long I was being punished for.”

By December of that year though, Walcott retired, and famed boxing referee Larry Hazzard took over the position, bringing in a fresh energy and new direction.

Ward’s family, friends, and support team immediately began writing to and calling Hazzard insisting on getting the young fighter reinstated.

“I wasn’t even a month on the job and I was getting inundated with messages to have this kid from Massachusetts suspension lifted,” Hazzard laughed thinking of the memory. “I figured if he fights in the ring with the same passion his family and friends are fighting to get him down here, what do I have to lose? Waiving Micky Ward’s suspension is one of the best decisions I’ve ever made.”

Given a clean slate from Hazzard, Ward made his Atlantic City debut on January 10th, 1986 at Resorts International Casino. He earned his third straight victory via stoppage, and with that kicked off a relationship with Atlantic City boxing that is forever engrained into ‘America’s Most Famous Boardwalk.’

“I really enjoyed fighting down in Atlantic City,” Ward reflected. “It’s a different kind of fighter down there. I fought a lot of guys from Philly and New Jersey, who even though they didn’t always have the best record, they were tough. They could fight.”

Ward fought and won seven times in Atlantic City in 1986, raising his professional record to 9-0 during that stretch.

Of the 51 bouts in his career, 22 of them were fought in AC, more than in any other city.

“The early Atlantic City fights really helped develop my career,” Ward said. “ I was fighting every month early on, and it really helped progress me. I went from a 4-round fighter, to a 6-rounder, to an 8-rounder, then to a 10, all down there. We all piled onto the bus every month -family, friends, and anyone else that wanted to make the trip. Sometimes the fights on the bus heading down were even better than the ones on the card!”

Another factor coinciding with the Atlantic City fights, also aiding the progression of Ward’s career, was the visibility he received on national television through ESPN’s Top Rank Boxing program.

As part of their initial launch into cable television in 1980, the upstart all sports network, pegged Atlantic City as a homebase for their weekly Saturday night fights..

The original Top Rank Boxing would eventually become the longest-running cable and weekly boxing series in history after celebrating its 16th consecutive year in 1996.

And what would eventually be 28 of his career bouts fought on ESPN’s Top Rank Boxing, Ward also holds the all-time record for most fights televised on the network.

Being able to make an impression with the network, and receive regular televised bouts early on, certainly helped him establish a wider national profile and fanbase.

“Luckily, Teddy Brennar (Top Rank Boxing matchmaker) liked me” said Ward. “He was friends with Johnny Dunn, Dickie’s old trainer, who was also working my corner. Teddy liked my style and I’m very fortunate he kept booking me.”

In August 1986, Ward returned home to the Lowell Auditorium to face the toughest challenge of his young career.

John Rafuse of Malden was 12-2 and, along with Ward, was considered the best young prospect in the Boston area at the time.

With Ward having looked impressive on a couple of his Atlantic City/ESPN bouts, Brennar decided to bring the Top Rank camera crews up to Lowell for the contest, which ended up being a clean sweep on the judges cards for Ward.

“Those were close rounds though, he gave me all I could handle,” Ward said of Refuse. “John was a good fighter.”

Following two more convincing wins bringing his record to 12-0, Ward then got the call to be on the undercard for the April 6th, 1987 ‘Fight of The Century,’ also marking the first time he would head out west to fight in Las Vegas.

About 50 miles south of Lowell, ‘Marvelous’ Marvin Hagler, training out of the Petronelli Brothers Gym in Brockton, had terrorized boxing’s middleweight division for the last fifteen years.

With a record of 62-2, Hagler had never faced an opponent he hadn’t beaten. In 1976 he dropped a pair of controversial decisions at The Spectrum in Philadelphia to local fighters Bobby Watts and Willie Monroe, before avenging those losses by brutally knocking out Monroe twice and Watts once in the ensuing years.

By 1987, Hagler was regarded as the greatest middleweight of all time, with only one name left to beat in his era: Dickie Eklund’s old foe, Sugar Ray Leonard.

A Hagler-Leonard superfight had been rumored for the better part of the decade, and in the spring of ’87 matchmakers were finally able to put it together.

And Irish Micky Ward would be on the undercard.

“I was the third bout of the evening. You know you’re on the undercard at Caesars Outdoor Arena when it’s still light out for your fight,” he said with a laugh.

The contest was scheduled for eight rounds, but Ward only needed four to end Kelly Koble’s night.

After his fight, Ward and crew cleaned up and were able to snag a few seats in the eighth row for the main event.

“That was such an experience for a young fighter, to be part of that atmosphere and to watch that fight (Leonard-Hagler) in person,” Ward acknowledged. “I was a big Hagler guy, we were all pulling for him.”

In what has gone down as one of the most talked about fights -and decisions- in boxing history, Leonard was able to pull out a split decision over Hagler by ‘stealing’ the final seconds of many key rounds in the fight. Devastated by the loss (and later frustrated when a potential rematch never materialized) the great Marvelous Marvin Hagler retired after that match, never to fight again.

“You have to give it up to Ray,” Ward admitted. “He fought an incredible fight.”

CHAPTER 3 – Setbacks in the Ring

FOLLOWING the TKO victory in Las Vegas, Ward and his team were back down in Atlantic City four months later with a pair of scheduled bouts to close out the year.

In August, short work was made of prospect Derrick McGuire earning a second straight fourth round stoppage, and raising his record to a spotless 14-0.

The plan was to take one more fight a month later, and then enjoy a few months off for the holiday before coming back in 1988.

His opponent was a familiar name: Chelsea, MA native Edwin Curet, who despite coming in with a record of 21-7, had given Top 10 ranked fighters Livingston Bramble and John Duplessis all they could handle.

The bout went back and forth all ten rounds, with Ward coming out on top in overall points, but dropping a razor thin split decision on two of the three judges scorecards.

“That was unfortunate,” he says looking back. “Curet was a really good fighter though. He kept the pressure on me all night, and did a good job making things a little uncomfortable in there. It could have gone either way, but he deserved to win.”

Ward took off the next three months to regroup back home -as planned- before returning to Atlantic City, to rattle off four straight wins to begin the year in 1988.

With his record now at 18-1, the next challenge was in the form of Philadelphia fighter, Mike Mungin. The fight -and lead up to- has become one of the more infamous scenes in the 2010 biopic The Fighter.

Mungin, a replacement for Ward’s original opponent, Saoul Mamby -who ringside doctors would not let enter the ring that evening due to a fever- came in twenty pounds (of muscle) over the weight limit.

The movie portrays his mother Alice, who was helping to manage Ward’s career at the time, and brother Dickie as strongly encouraging him to take the fight regardless so they could all still receive the scheduled pay day.

“None of that was true,” Ward clarified of the controversial scene. “The movie made it look like my mother and brother were pressuring me to fight, but I’m the one that wanted to fight. I had been training, I was in shape, I was ready. All they did was ask me what I wanted to do, and the decision to fight was all mine.”

Despite giving up three weight classes, Ward hung in the fight gallantly against his larger foe, coming up just short on the final scorecards, 94-95, 94-95, 93-96.

“The fight was close,” he said. “But I don’t think I did enough to win. I was alright with that decision.”

Ward was back at Resorts Atlantic City in December, making quick work of Brazilian brawler Francisco Tomas da Cruz via 3rd round TKO, which set up a title bout versus Frankie Warren at Caesars AC in Janaury 1989 for Warren’s IBF USBA Super Lightweight belt.

Warren, coming in with a record of 28-1, was an extremely skilled pundit whose only blemish was a 12th round KO loss to Buddy McGirt (future HOF inductee and future trainer to Arturo Gatti) a year ago.

The twelve round title bout was competitive throughout, but Ward ultimately dropped the decision on all three judges scorecards: 113-115, 112-116, and 111-117.

As it turns out, that loss to Mungin back in September (1988) was the beginning of the toughest stretch of Ward’s career. Over the next three years -and his next nine fights- he would lose six times. And although remaining competitive in defeat -having his moments in each of the losses- he knew something was off.

“I lost my edge. I lost my will a little,” Ward reflected. “I was still training hard and doing what I had to do to prepare myself physically, but once your confidence gets even slightly shaken, it’s hard to come back from that.”

Even still, the opponents being offered -and the fights Ward was accepting- were some of the top guys at that time.

“I should have taken a couple of easier fights after a tough loss,” he admitted. “They (the matchmakers) started treating me as an opponent rather than a prospect. I went from having guys fed to me to me being the one fed to the top fighters.”

True to form, Ward refuses to make any excuses for himself and pays the highest respect to the guys that beat him during this time.

“Charles Murray was a helluva fighter, one of the better guys I fought. He could box, and he could punch too.”

On Harold Brazier: “That’s one guy no one gives enough credit too. He was tough, a really smart fighter, and one of the better gentlemen in the sport.”

On Tony Martin: “Another really tough fighter out of Philly. He was damn good.”

And although things may have been a little sluggish in the ring, there was the greatest joy entering Ward’s personal life back home.

In 1989, he celebrated the birth of his daughter, Kasie. With his baby girl in Lowell and the mental edge for boxing somewhat waning, the appeal of spending half of the year down in Atlantic City fighting wasn’t the same as it was a couple of years earlier.

“I basically said ‘f**k that, I don’t want to do this anymore,’” concluded Ward.

So in 1991, Micky Ward retired from professional boxing to concentrate on being a father to his daughter and to work and live a regular blue-collar life.

CHAPTER 4 – Retirement – Part I

BACK home full-time in Lowell, Ward was doing in his retirement from boxing exactly what he planned to do:

He spent as much time as he could with Kasie.

He fell into the routine of a normal work day that didn’t also involve having to train and fight. (Throughout his early career, Ward maintained a construction job while fighting, essentially working two full time jobs.)

And for the first time in ages he actually got to enjoy a little relaxation and down time.

He was also over at the Middlesex House of Correction -not as an inmate, but working as a correctional officer.

“When I first started at Middlesex, there was a lot of guys I knew growing up who were in there, and they were asking ‘Hey Micky what are you in here for?’” Ward recalled. “I looked at them and said ‘To work! What do you think I’m doing here?’”

Friends and family would ask if he missed fighting, and the answer was always the same:

“I would tell them I was good with where I am at. I’m happy doing what I’m doing,” Ward said.

There was at least one person in Lowell that wasn’t buying it though. Police chief Mickey O’Keefe, a close friend and mentor of Ward’s and himself a former golden gloves boxer came by to see Ward one afternoon.

“Dickie was locked up at the time, and Mickey asked me just to swing by the gym and work out with him a little,” Ward revealed. “It was a no pressure offer so I did. As soon as I got back in there it felt good. I did miss it. Slowly I started getting in there a little more and more and before you knew it we were training somewhat regularly.”

As part of that training, O’Keefe implemented a host of strength based drills and exercises his son Shaun’s college wrestling coach was using to transform the bodies of his wrestlers.

The results gave Ward a new level of raw strength, and confidence.

“When I first retired, even up until my late 20’s, I had a body that looked like I was in my early 20’s,” Ward said. “The program and training I began doing with Mickey helped fill me out. It gave me man strength.”

The tight knit circle he was training with was noticing too. Ward was hitting the heavy bags with more force, knocking down more partners while sparring, and looked physically more imposing than ever before.

“I was 100% physically stronger,” Ward stated. “I was no longer just throwing punches to throw them, I was throwing punches with meaning.”

The itch for a comeback was there. It had been three years since he last fought, and Ward missed the sweet science that had engulfed him since he was seven years old. He began thinking about local fights, but wanted to be sure this time around there would be a seismic difference in his approach.

“I wanted to fight for me. I wanted to do this for myself,” he said. “The first part of my career I was doing everything I felt like I was supposed to do, or what other people wanted me to do.”

There was a second noticeable change as well. Before his retirement in 1991, Ward’s style was similar to his brother Dickie’s. Lots of boxing, lots of movement. With the new physique and his increased power, he wanted to refine his approach in the ring.

“I wasn’t going to be dancing anymore,” Ward said. “I was going to move forward and punch with intention.”

CHAPTER 5 – The Comeback

WANTING to make sure he didn’t fall into the same patterns that plagued him before his first retirement, Ward began his comeback with a series of tune-up fights locally to shake off any ring rust that could be lingering.

Over the next three years, he fought and won five times -twice in Lowell, and three times at Wonderland in Revere- each bout ending by either KO or TKO as a result of Ward’s new style of fighting.

“Those fights only paid me about $400 or $500 each, but they were exactly what I needed to get going again,” Ward said.

That set up a match with Louis Veader, a slick boxer out of Providence, who boasted a perfect 31-0 record.

“I was training out of World’s gym in Somerville at the time, and we got the call offering us Veader,” Ward said. “He was a very good boxer and was getting his push.”

The fight on April 13th, 1996 at TD Garden was for the WBU Intercontinental Super Lightweight title. For Veader’s group, Ward seemed like the logical next step before bigger fights and bigger pay days.

Apparently, they hadn’t paid enough attention to the new Micky Ward, however.

“In the ninth round I ended up catching him and that was it,” Ward shrugged.

It was his sixth straight win and sixth straight knockout since his return to boxing.

Stunned by the loss, Veader’s handlers insisted on an immediate rematch, which Ward granted. Three months later he upended Veader again -this time at Foxwoods Resort & Casino in Connecticut.

Ward was now rolling in his comeback and was, behind the scenes, beginning to assemble the team he hoped would be able to strategically land him the right fights -and bigger pay days- as he entered the latter part of his career.

He entrusted local businessman Sal LoNano to take over some of the management. Eventually LoNano and Ward pieced together a team that included: Al Valenti (promoter); Bob Trieger (publicist); Al Galvin (cutman) and in time Dickie back (trainer) as part of the core.

LoNano immediately got to work. Buoyed by the back to back impressive wins over Veader, Ward’s brass was able to secure a showdown -and first six figure purse of his career- against all time boxing great Julio Cesar Chavez.

Chavez possessed an otherworldy record of 97-2, and was hailed by many as the greatest Mexican prizefighter of all time. The bout, scheduled for December 6th, 1996 in Reno, was easily going to be the biggest of Ward’s career.

But as the countdown to fight night crept closer, strange things began happening. Chavez twice delayed his scheduled arrival into Reno, citing a sore throat; and rumors abound that he was in the middle of an ugly family dispute.

Then, on December 1st, five days before the fight, Chavez pulled out of the match, claiming he hurt his hand while training.

Ward’s massive fight -pay day- were off the table, just like that.

Against the advice of everyone on his team, Ward agreed to a last minute replacement; for a tenth of the paycheck he was scheduled to receive against Chavez. His new opponent was a rugged Mexican journeyman named Manny Castillo, who -despite a modest 13-6 record- had a reputation of getting the better of many elite fighters in sparring sessions.

“I know it wasn’t the smartest thing to take that fight,” Ward said. “But what was I supposed to do? I was frustrated. I had trained my ass off to fight. We were already in Reno, and I needed a paycheck.”

What ensued was ten rounds of a see-saw slugfest, Ward escaping with a narrow split decision victory.

“It would have really sucked if I lost that one,” he admitted.

Ward’s next fight, and first in 1997, was lining up to be another potential barnburner.

Alfonso Sanchez was 16-0 and considered one of the rapid rising stars in the sport. He could both box and hit hard.

With Ward looking really comfortable in his revamped style of moving forward and punching with intention in fights, this bout had many in the boxing universe buzzing with anticipation.

But for whatever reason, once the bell rang, Ward reverted back to his older style of fighting.

“I was running and dancing,” said Ward. “But I just wasn’t throwing any punches. I’m not sure exactly why I was fighting that way. I’ve always been a little bit of a slow starter, and for whatever reason I couldn’t get comfortable so I just kept moving.”

By the fourth round, the crowd -and announcers- were growing restless.

“If either of the fighters in the upcoming main event (Oscar De La Hoya vs Pernell Whitaker) need to take a snooze before the next fight, just show them this one in the dressing room,” HBO’s Larry Merchant mused.

By the sixth round, referee Mitch Halpern -and even Ward’s corner- were threatening to stop the fight due to lack of activity and aggression from him.

“I caught him at the end of the sixth with a little bit of a body shot and saw that it hurt him some,” Ward said. “I don’t even know if everyone saw it, but I was yelling back at my corner ‘don’t you dare stop this fight! I got this!’”

The seventh round started a little slow again, but by the middle of the round Ward began to dig in, and was looking for his patented body shot.

Then at the 1:19 mark, a swift left hook tapping the head, followed by a crushing left hook to the liver, put Sanchez down for the first time in his career.

Larry Merchant, who very well may have actually fallen asleep on the job, uttered: “What am I looking at here?”

Jim Lampley put it more poetically: “Did Micky Ward just make idiots of us all with a spectacular piece of strategy?”

“After I put him down, I was jumping all around and everything, making it look like I was ready to keep going,” said Ward. “But inside I was praying ‘please don’t get up’ and when he didn’t I said to myself ‘thank God, now let’s just get out of here.”

The knockout extended Ward to 9-0 with seven of those wins via stoppage since coming out of retirement. Sanchez, ironically enough pegged by many as boxing’s ‘next Julio Cesar Chavez’ had just been put down by Ward for a ten count that easily could have gone to fifty.

Team Ward was ready and on the hunt for bigger fights. Four months later, they got one.

Vince Phillips, a talented scrapper from Florida, had just upset super prospect -and previously undefeated- Kostya Tszyu in the tenth round in Atlantic City to win the IBF Super Lightweight championship.

Phillips agreed on his first title defense against Ward, and also agreed to it being in his backyard at The Roxy in Boston.

Scheduled for twelve rounds, as expected, The Roxy was packed with a boisterous pro-Ward crowd on this hot August evening.

In yet another dose of misfortune that was beginning to eerily feel somewhat of a big fight pattern, Phillips caught Ward in the third round with an overhand right that split the skin, and opened scar tissue above his left eye.

“It didn’t hurt but as soon as he hit me, I knew it wasn’t good,” Ward says. “I could see it on the faces of everyone in my corner too when they took a look at it. It was a very deep cut.”

Both Ward and his corner wanted the fight to continue, but once ringside physician Patty Yoffee took a look at the eye she waved the contest off.

Ward began protesting to Yoffee, but quickly turned his attention in horror back to Phillips, who was getting bombarded in the ring with debris from the rowdy and now angry hometown crowd.

“A lot of stupid asses, were throwing stuff at him and half of them were from my family,” Ward said. “Beer cans, cups, whatever they could get their hands on. I was like ‘what are you doing, it isn’t his fault. He didn’t headbutt me, it was a clean punch!’”

Once both Phillips and Yoffee were safely out of harm’s way, Ward went to MGH to get the eye stitched. It was there he realized the extent of the significance Yoffee’s stoppage meant to his long-term health.

“The doctors at MGH told me that if the fight had continued and the cut went even a little deeper, it would have damaged the eye muscle movement and I could have lost my eye,” he recalls. “She’s (Yoffee) a good doctor. Thank God she stood her ground and did what’s best for the fighter and not just what everyone emotionally wanted her to do.”

Ward took the next eight months to let his eye fully heal and to also give his team time to plan the next move. Because of the fluke nature in which he lost to Phillips, he wasn’t really penalized in the rankings, and was still in good position for a bigger fight.

Another rising sensation, Zab Judah, was being dangled as a potential pairing, and Ward was open to the idea of fighting the lightening quick uprise from Brooklyn, NY.

On April 14th (1998) Ward took a tune-up fight at Foxwoods, making quick work of journeyman Mark Fernandez in the third round.

Judah, to help hype the looming showdown with Ward, jumped on the same Foxwoods card and made even quicker work of Angel Beltre, finishing him in round two.

The stage was set on June 7th in Miami for another “future of boxing’s brightest stars” to get an early test against a now grizzled and gritty veteran in Irish Micky Ward.

There are two adages in boxing that have withstood the test of time: 1) styles make fights and 2) speed kills.

“He was really fast,” Ward said looking back now on the Judah fight.

Yet, Ward kept coming forward.

“He was tagging me too, he had some pop in his punches, even at (age) nineteen.”

Judah swept through the first seven rounds, but Ward kept in pursuit, nonetheless. In the eighth, he finally caught up and was able to rip a few left and right hooks to the head and body of the young phenom.

A liver punch mid-way through the round -although not totally on spot- buckled Judah and the two-time amateur national champion hunched over in pain. Looking like Judah may drop to the canvas for the first time in his career, Ward pranced, going for the kill.

Somehow, Judah gathered himself and survived the on-slaught, showing the mettle that would one day help him earn world championships.

“I almost had him,” Ward says. “Give the kid credit. He recovered fast in between the eighth and ninth round too.”

Although unanimous across the board on the scorecards, earlier this year, Judah was quick to credit Ward as the toughest fight of his career.

“Micky Ward was my toughest opponent,” he stated. “Because I was 16-0, fighting a legend, and he had a body punch that would stop a donkey.”

He continued: “I never had to use my mind capacity the way I had to use it in the Ward fight. That was hard. I’ve been fighting my whole life, there’s nothing physically hard for me. But I never had to use my brain and mind capacity as I did in the Micky Ward fight.”

CHAPTER 6 – Fight of the Year

IT would be a year and a half before Ward was back in a high-caliber match following the Judah setback.

In that time he knocked out two journeyman fighters to remain sharp; having learned lessons on how to better select opponents after a tough loss from earlier in his career.

On October 1st, 1999, Ward was set to square off with ‘Showtime’ Reggie Green, in Salem, NH in a fight that had boxing afficionados and insiders everywhere gushing.

Green, a slick puncher universally ranked in most top five polls at junior-welterweight, entered with a record of 30-3. In his last bout he took WBA Super Lightweight champ Shamba Mitchell to a majority draw.

From the opening bell, it was apparent to everyone watching, this was going to be a dog fight. Ward, notoriously a slow starter, was having early difficulties figuring out the crisp punches and controlled distance of Green. But by the end of round two he delivered one of his trademark hooks and the brawl was on.

Ward landed another big shot to start round three, but after missing a right cross, Green connected with a massive left hook.

“When he caught me with that punch, I thought I was on Highway Route 93 behind us. I had never been hit so hard,” Ward said. ‘That left hook split a big hole in my lip. It ended up needing fifteen stitches. I could put my tongue right through it.”

Ward staggered to the ropes and was on rubbery legs. Green went in for the kill letting both hands fly. Somehow, defying all logic, Ward didn’t go down.

For the next five rounds, the two gladiators would go at each other at a frantic pace with Green winning most exchanges by battering Ward outside before he could get inside to fight.

Ward seemed more than willing to eat two punches to give one and kept pushing forward even though he was falling behind on points in doing so.

Then, in the eighth Ward, who at this point looked like a butchered character from a horror movie, invited Green into the phone booth and the two stood toe-to-toe and slugged. The ninth was more of the same, and Green although continuing to give to Ward was now getting it just as bad. Both men were exhausted.

The tenth round was one for the ages. Ward caught Green with a jackhammer left hook that staggered him to his corner.

Like a predator chasing its prey Ward hunted down Green and savaged him with a series of left hooks. He continued his pursuit with a furious assault, delivering with both hands, including devastating shots to the body.

Just as referee Norm Veilleux moved in to stop the fight, Ward sent Green crumpling to the canvas with one last left hook.

It was the signature win Micky Ward was looking for and needed, and he did it in dramatic style, coming from behind.

Afterwards, ESPN’s Teddy Atlas summed up the fight:

“That truly was fighting. That was not entertainment. That was not business. That was fighting. This is a barbaric thing at the core of it. It ain’t always pretty but it’s real. Like the mobsters say, that was a real guy up there. When it came down to what a fighter is about, Micky Ward was it. That is what a fight is and you don’t see it too often no more.”

Word of the Green-Ward instant classic circulated fast throughout the boxing cosmos, and with it came a wave of momentum and new opportunity.

Now possessing an overall record of 34-9 (13-2 since coming out of retirement five years earlier) Ward, who turned 34 three days after the win over Green, was laying out what he wanted over the final few years of his career.

“I wanted a shot at fighting for a title and I wanted some big names,” he said. “It’s funny what one fight can do for you in this sport. If I hadn’t beat Green, and I was losing on the cards before I stopped him, I was going to really have to take a hard look at what I was actually doing with all of this.”

He would get just that. Liverpool’s Shea Neary had compiled a record of 22-0, and in the process become the longest reigning WBU champion ever -across any weight class- holding its Super Lightweight belt for the last four years, with five consecutive title defenses.

The UK fighter’s promoters reached out to Ward and asked if he’d be interested in a title bout in March. With one caveat: Neary only fights on his home turf.

“I said sure, we’ll head to Britian,” Ward replied.

When Ward and crew touched down in London they were met by an overconfident Neary and fanbase, who brought a lot of pre-fight theatrics.

“The fans booed me pretty good as I came down to the ring,” Ward recalled. “But they were respectful after.”

The fight itself, scheduled for twelve rounds, was another good one. Neary came out in a more conventional boxing approach behind his jab, while Ward looked to walk him down and land power punches.

Ward connected with a big body hook in the first round that hurt Neary, but in round three was hurt himself by a well-placed temple shot. In the fourth, Ward again landed a powerful body blow that visibly stunned the champion.

Neary responded well in the middle rounds, and by round eight, appeared to be slightly ahead in a very competitive fight.

Then Ward did what Micky Ward does. A body hook/left uppercut combo sent the champion crashing to the canvas. Credit to Neary, who got up, but moments later an identical combo put him down again ending the fight, and Neary’s four year reign as WBU champion.

“I knew I was going to beat him that night,” Ward recounted. “There was something inside my head. They (Neary’s camp) were so confident and never thought they would lose.”

The stunned British crowd watched in dismay as their battered former champion was helped back to his corner. Believing their fighter was ahead on points, and perhaps knowing there could be a little hometown cooking in the scorecards had the fight gone the distance, almost everyone in the Kensington Olympica Arena were stunned.

Almost everyone. In the HBO booth that night was an old man, who had learned his lesson three years earlier. He had seen this before.

Larry Merchant shook his head, and simply stated: “He’s done it again folks.”

BACK in the USA, and with his last two wins arguably being his two best, Ward was the closest to the top of his division he had been career-to-date.

RING Magazine named his brawl with Green the 1999 ‘Fight of the Year’ runner-up (to Johnny Tapia vs Paulie Ayala).

“We were hoping to be next in line for a title fight with Kosta Tszyu,” Ward recalled of the mindset after the Neary win.

The late 90’s/early 2000’s were an incredible time for the super/lightweight division. It was loaded with talent and very crowded at the top. Tszyu was at the peak of his powers, having just dismantled Julio Cesar Chavez in July (2000) and was in the process of unifying the WBC, WBA, and IBF belts in the division.

The timing of a Tszyu-Ward fight wasn’t lining up, and there were other matches to make- so Ward ended up in a contenders bout with Antonio Diaz in August at Foxwoods.

Davis (34-2), like Ward, was stuck in the log jam of the division. Both fighters were told the victor would receive the elusive big name or title fight after this match.

The fight didn’t disappoint. In another very competitive contest, Ward -after seven rounds- was up 67-65 on most scorecards.

“Then in the eighth, he hit me with this straight punch right between the eyes,” explained Ward. “It didn’t really hurt the way a big punch usually does in terms of dazing or wobbling you.. it was more like a hammer whacked right in between the eyes. I could feel his knuckle at the bottom of my forehead when he hit me.”

That punch sparked a rally for Diaz. Although the last three rounds were super close, they all went in his favor, resulting in a 94-95 decision loss for Ward.

Diaz’s next bout -as promised- was the big pay day and title shot against Sugar Shane Mosley at Madison Square Garden.

For Ward? A matchup against formidable southpaw prospect Steve Quinonez, a good fighter but also clear step backward at this point for him.

ON May 18th, 2001 when Micky Ward stepped inside the ring with Steve Quinonez at Foxwooods Resort & Casino, it had the feel of a ‘win or retire’ match for The Pride of Lowell. A second straight loss in a crowded division would be decapitating.

“Finally, we were able to catch a break,” Ward said smiling.

At 3:03 of round one, Ward drilled Quinonez with a double left hook to the head before curling him up with a beautiful hook to the solar plexus.

Short work, no injuries, and a devastating early KO of a good opponent. It was exactly what was needed for Ward to re-establish his spot in the rankings.

The first round knockout ended up being pivotal in lining up the timeline of future events, and history to unfold over the next two years for Ward. Had he endured a ten round all-out war with Quinonez, he would have been on the shelf recuperating for six months before his next bout.

But leaving that fight fresh and unscathed allowed him to book his next match less than two months later, a summer showdown on the Hampton Beach Boardwalk against Emanuel (Burton) Augustus.

To the novice boxing fan, a quick glance at the booking of Ward vs Augustus probably doesn’t make sense.

Ward quipped: “If you just wandered in off of the Hampton Beach Boardwalk that night, picked up a program and looked at our records, you’d say ‘Why the hell is Micky fighting this guy? He’s gonna kill him!’”

Emmanuel (Burton) Augustus arrived at Hampton Beach Casino on July 13th, 2001 sporting a journeyman type record of 24-17.

“I knew better though,” Ward cautioned. ‘This guy could fight. He had a bad habit, especially earlier in his career, of showing up at his matches without having trained at all. But whenever he put in a full camp he was a different fighter.”

Two years earlier, Augustus got into the phone booth with the same Antonio Diaz Ward recently fought, out-landing the IBA Light Welterweight champ in punches, 231-207, despite dropping the twelve round decision.

And nine months before the showdown with Ward, Augustus nearly took Floyd Mayweather, Jr the cards.

How good is Augustus? This is what Mayweather told reporters in 2012:

““I’m going to rate Emanuel Augustus first compared to all the guys that I’ve faced,” Mayweather said. “He didn’t have the best record in the sport of boxing, he has never won a world title, but he came to fight.”

What then transpired that evening on Hampton Beach over ten rounds is the stuff of legends.

The majority of the fight saw the two warriors standing right in front of each other. Ward was able to walk Augustus against the ropes for a good portion of the evening, where Augustus was more than comfortable exchanging punches.

Ward ferociously implemented his body attack strategy, which Augustus took and often smiled. He would return fire at Ward’s chin, failing to dent or even phase him.

At the end of round four Teddy Atlas, calling the fight for ESPN, implored viewers at home:

“Fans, at this break, call all your friends. We’re in the midst of a classic.”

With Ward utilizing a high guard, Augustus -in the seventh round- switched up and started throwing body shots of his own.

“He hit me with one in the seventh,” Ward said. “It was the hardest body shot I felt over my entire career.”

In the ninth, Ward was finally able to put Augustus down with his classic left hook kidney shot. On his knees in tremendous pain, Augustus remarkably was able to rise, and even more incredibly began taking the fight back at Ward.

In the tenth and final round, with everyone in the crowd roaring both gladiators on, Ward and Augustus fought to the final bell.

In a brawl that RING Magazine would later name its 2001 “Fight of the Year” the two men combined to throw over 2100 punches with Augustus landing 421 to Ward’s 320.

Ward took home a unanimous decision victory, and Atlas -who himself scored the fight a draw- plead to all the boxing powers that be: “Give Micky Ward a money fight! GIVE THIS GUY A MONEY FIGHT!”

Note: Years later, we found out just how insanely logic defying tough Augustus was. In 2014, he was shot in the head -took an actual bullet to the head- yet got up off the ground and survived. Let that sentence sink in.

FOLLOWING the all-out war with Augustus, Ward had once again positioned himself for the elusive money and/or title shot he had previously been so close to.

Aided by the cries of Atlas and others with influence -and an increased demand from fans across the globe- it was becoming more and more evident that Ward would be making that final leap.

Whoever and wherever his next opponent would be was going to be a critical decision. Enter Lou DiBella.

DiBella was, and remains today, one of the more influential figures in professional boxing. He and Ward had aquaintances with each other from the days when Micky was fighting regularly on ESPN in Atlantic City.

A meeting was arranged in New York City, and DiBella laid out a three fight proposal for Ward that would check both the big money box and give him fights that were good pairings to further enhance his growing legacy.

The plan was to first fight perennial contender Jesse James Leija (42-5) a fighter who had recently moved up in weight class; and then either a world title bout against Kostya Tszyu (who had just handed former Ward foe Zab Judah the first loss of his career via 2nd round KO); or potentially a ‘styles make fights’ matchup with Arturo Gatti.

Ward and DiBella hand-shook on the deal and the plan was in place.

“DiBella delivered,” declared Ward. “He got me $250k for the Jesse James Leija fight, which at that point was by far the biggest payday of my career.”

There was only one caveat: the fight had to be in Leija’s hometown of San Antonio, Texas.

So on January 5th 2002, Ward entered the Freeman Coliseum with everything he ever dreamed of in professional boxing being a mere one win out.

“The plan was to put him away,” says Ward. “I knew we weren’t going to get favorable judging in his backyard. My goal was to get busy early.”

Two minutes into the fight, it appeared Ward’s strategy would work to perfection. After landing a hard left hook to the head, blood began trickling out of Leija’s eyebrow. Things were looking good.

Inexplicably, however, referee Laurence Cole then jumped in, paused the fight, and told the ringside judges to ignore the impact of the cut because it -he claimed- was the result of an accidental headbutt. Multiple replay angles confirmed this to be an absolute egregious ruling by Cole.

Ward, distracted by his own frustration from the unfair call, didn’t implement his game plan the next couple of rounds, perhaps costing him valuable points.

By the end of the fourth -once the fight was official in the rulebook regarding injuries caused by an ‘accidental headbutt’- Leija and his corner cried for a medical emergency claiming there was no way the proud Texan could continue due to the insurmountable damage of the ‘headbutt.’

The outcome was going to the judges scorecard. Duane Ford (from Las Vegas) had the bout 48-47 for Ward; Ray Hawkins (Texas) scored it 48-47 Leija; and Gale Van Hoy (Texas) -through her Lone Star goggles- went 49-46 Leija.

Micky Ward had unfairly lost an injury shortened split decision under crooked circumstances.

Luckily, Lou DiBella and HBO agreed. Before Ward had even left the arena DiBella assured him he would not be penalized for the controversial loss; their handshake agreement was still in place.

Technically, because Leija ‘won’ the match, he would be next in line for the title shot with Kostya Tszyu.

But the lane should be clear, DiBella said, to make the alternative fight with Arturo Gatti happen.

“That’s the one I wanted anyways,” Ward told him.

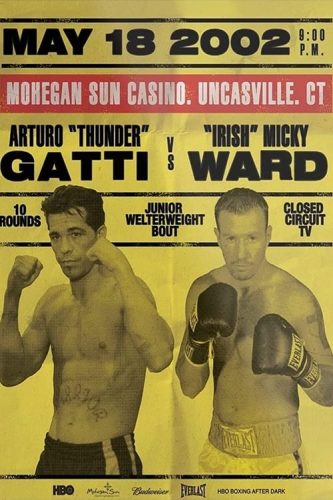

CHAPTER 7 – The Making of Gatti-Ward

ARTURO “Thunder” Gatti, simply put, was one of the most exciting and enigmatic fighters of the generation.

In the spring of 2002, he was sitting at a record of 34-5 -with tons of star power- but also was at a slight crossroads in his career.

For his first seven years as a professional (30 bouts) he fought mostly at 130lbs, dominating the Super Featherweight division as its champion from 1994-97, going 29-1.

In 1998 he made the jump up to 135, losing a tough TKO to Angel Manfredy, due to a doctor stoppage because of a cut over his eyes. And then dropping two razor thin decisions to Ivan Robinson, the first which captured RING Magazine’s 1998 ‘Fight of the Year’ and the second due to a critical point Gatti had deducted in the eighth round for low blows (file that note for future reference).

Despite going 0-3 at 135, Gatti fancied visions of a superfight against Oscar De La Hoya, and continued to add muscle to his frame in order to move up in weight.

His next two fights were at 140, where he made very short work of both Reyes Munoz and Joey Gamache, before coming in four pounds overweight for a scheduled 145 bout that he destroyed Eric Jakubowski in. He then outpointed Joe Hutchinson in his home city of Montreal at 145, and that -in the eyes of the promoters- was enough to get him the mega-matchup with De La Hoya.

Fighting at 147, De La Hoya’s natural weight class, Gatti was outclassed from the opening bell. He went down in the first and was battered for the next five rounds, until his corner mercifully threw in the towel.

AS Lou DiBella and Micky Ward chatted in the immediate aftermath of his match with Leija, he predicted to Ward that Gatti would be more comfortable going down to 141, where he had a fight in three weeks against Terron Millett.

He had jumped up in weight classes way too fast, DiBella reasoned, and had no business being at 147 with De La Hoya anyhow. If things went well on 1/26 vs Millett for Gatti, DiBella said, he felt confident about putting together a Ward-Gatti fight at 141 in May.

Three weeks later, after Gatti impressively stopped Millett in the fourth round, Micky Ward had the fight he had worked -and waited- his entire career for inked for May 18th at Mohegan Sun Casino in Connecticut.

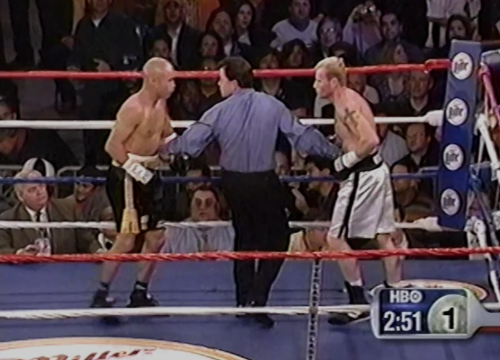

CHAPTER 8 – Gatti-Ward I

THE public hype and anticipation going into Gatti-Ward I was the highest it had been for one of Ward’s fights. Between the two of them, they had been involved in three of the previous five ‘Fights of the Year’ with Ward’s classic against Green in ’99 easily could have been making it four of the last five.

The purse, $400,000 for Ward was his highest as well.

He ran his camp in Tewksbury, MA for the fight, with his brother Eklund running the show.

“It was one of the best camps I’ve ever had,” Ward said years later. “Dickie did an incredible job. I felt like I was in my 20’s again.

Ward entered the ring on May 18th 2002 at Mohegan Sun with an overall record of 37-11. This was th 49th and professional bout of his career. Since coming out retirement in 1994 he was 16-4. Gatti, meanwhile, was sitting at 34-5 overall, and 5-0 fighting at 140 lbs.

NOT even halfway through the first frame, Ward was already cut. A left hook from Gatti, sliced the scar tissue outside of Ward’s right eye, and blood was trickling down his face.

Gatti came out boxing, frustrating Ward early and easily took the first two rounds.

Ward looked stronger in Round 3 and then at 1:07 in the fourth rocked Gatti with a straight right hand.

With under thirty seconds remaining in the round Gatti buried his left hand below Ward’s waistline, an unintentional -but clear- low blow. Referee Frank Cappuccino called time and deducted a point from Gatti for the infraction.

Inexcusably, the timekeeper did not stop the clock during Ward’s allowed recovery time (up to five minutes when rattled in the family jewels) and the round came to an end seconds later.

Now Round 5 was set to begin, and Ward only had a minute to compose himself. Dickie and Cutman Al Galvin were furious in the corner, screaming at whoever would listen.

“I’m ready to fight,” Ward told them. “Let’s go!”

And fight he did in the fifth. In a hellacious round that would epitomize the next 25 to come between these two men, Ward began to turn the match into his type of fight -a brawl.

At the 2:40 mark, Gatti unloaded a flurry of 12 unanswered punches that backed Ward to the ropes. Just as Gatti stepped back to catch his breath, Ward responded with his own 12-punch combo that sent Arturo spiraling. A hard left body punch and a straight right then had Gatti wheeling across the ring to the adjacent ropes. Ward ended the round by cracking Gatti with his best right hand of the night and a left hook for good measure.

“They’re fighting in a phone booth, and that’s the way Micky Ward wants it!” Jim Lampley exclaimed to the HBO audience.

Entering the sixth, both fighters were a bloody mess. Gatti -naturally the better and more skilled boxer- got back to boxing and moving. Rounds six and seven went to Gatti, as Ward struggled to get the fight back on the inside.

“I’m not going to let you be a punching bag!” brother Dickie screamed at Micky in between rounds. “Fight back!”

Ward needed a strong eighth round, and delivered.

Both fighters exchanged big blows throughout the round. Gatti landed two of the hardest punches he threw all night straight to the chin of Ward, but Micky ate them and kept moving forward. In the final thirty seconds of the round, Gatti was himself moving forward, unleashing combinations, but was stopped in his tracks by one pinpoint left from Ward, that clearly hurt him. He began backpedaling as Ward absolutely unloaded with everything he had. Gatti was responseless. When the bell rang signifying the end of the round, Gatti was dazed and wobbled as he stumbled back to his corner.

“Oh my gosh! Oh my goodness, what a fight!” Lampley gushed to the HBO audience.

The Greatest Round in the History of Boxing started with Ward immediately running straight to Gatti, getting back on him.

“I knew he was still hurt from the eighth,” Ward said. “So I wanted to try to put him away at the start of the ninth.”

And then fifteen seconds into the round it happened.

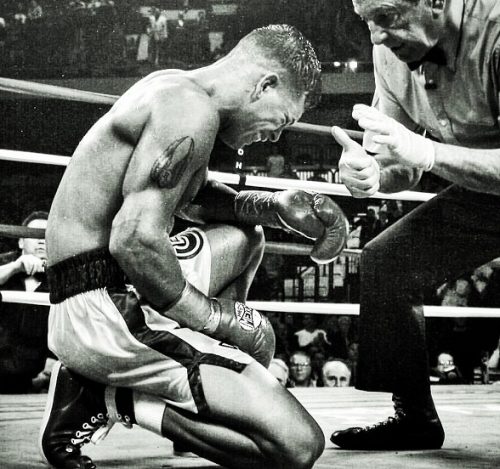

Ward tapped Gatti to the head and then ripped his trademark left hook to the liver. Gatti took two steps back and then dropped to one knee in excruciating pain.

In retreating to his neutral corner before referee Cappuccino could begin the count, Ward initially went to the wrong neutral delaying its start by a valuable second.

“PLEASE don’t get up!” Ward was thinking to himself.

It was the type of punch fighters -even the toughest professional boxers in the world- do not rise from. Gatti remained on one knee, and then somehow just as Cappuccino was about to say ‘ten’ he got up.

Still visibly in pain, the fight continued. Ward pounced, firing off 23 consecutive unanswered power punches. He had Gatti flying all over the ring like a rag doll, wincing in pain.

Micky kept punching, but Gatti refused to go down again.

“I just kept swinging and swinging,” he said until the lactic acid in my bicpes totally tightened and froze my arms.”

Now it was Gatti’s turn. Miraculously still on his feet, he fired a barrage of body shots at the exhausted Ward, who began to retreat. Gatti backed Ward into a corner, who nodded at his rival as if to say ‘Let’s go!’

The two warriors continued to exchange power combinations with reckless abandon. “Your turn, my turn.”

The fight moved back towards the center of the ring, with Gatti stumbling forward towards Ward, almost holding himself up on Ward’s body, while continuing to throw.

With under a minute left, Ward landed the left body hook again to Gatti’s body. Gatti was badly hurt and exhausted -but sill on his feet.

Ward went in for the kill. He unpacked nine consecutive power punches, blows that would make the bones of a man’s ancestors rattle, blows that spun Gatti sideways -Arturo was out on his feet, but still standing.

“You can stop it Frank! You can stop it at any time!” Jim Lampley was screaming into the HBO mic.

With ten seconds to go in The Greatest Round in the History of Boxing, the two gladiators exchanged exhausted combos once more.

“I don’t believe this, Gatti is going to survive the round,” Lampley said.

“This should be the round of the century!” Emmanuel Steward declared in the HBO booth.

“They have struck both the courage nerve and the nostalgic nerve,” Larry Merchant added.

In the ninth round alone, Gatti landed over 40 power punches. Ward landed over 60. And both men kept going. It was one of the most unbelievable displays of valor ever displayed in a boxing ring.

In between the ninth and tenth round, Gatti’s entire corner entered the ring. There was great concern among Gatti’s circle to let Arturo continue and to keep taking that type of punishment. A member of Gatti’s team waved his arm to end the fight.

Ward and Al Gavin jumped up and began celebrating, raising Ward’s hands in victory.

“Fight ain’t over!” Cappuccino began yelling. “One more round!”

Amongst the chaos of Gatti’s team entering the ring, stopping the fight, and then continuing it, the bell for the tenth round went off. By the time Cappuccino had restored order, thirty seconds were already passed.

Gatti began bouncing around and boxing again to start the round. Both men were absolutely exhausted, as the round, and fight came to its close. The two warriors stood in the middle of the ring and exchanged punches with reckless abandon. Toe to toe.

Merchant: “I am humbled by watching these two men. This is the way it has to end.”

Lampley: “We told you it would be a candidate for Fight of the Year. We didn’t know it would be a candidate for Fight of the Century.”

The final bell tolled, and the two fighters threw their arms around each other embracing in the ultimate moment of mutual respect.

Moments later, the judges scorecards were announced: 94-93; 94-94; 95-93. The winner by majority decision was Irish Micky Ward.

“Going into that first fight, I knew I was going to get beat up,” Ward told BostonMan Magazine for this story. “I knew I was going to the hospital after the fight. I knew I was probably going to need stitches after the fight. But I also knew I had a shot at beating him.”

It was the shot Micky Ward had been waiting for his entire life. And he did it.

CHAPTER 9 – Gatti-Ward II

THE universal response from the fight was instant and impactful. It resonated with people across different generations, different cultures and different demographics. From the hardcore boxing aficionado to the stay-at-home mom,

What Micky Ward and Arturo Gatti did on May 18th 2002 at Mohegan Sun mattered.

“When you’re in the fight, when you’re in the moment, you’re in there beating on each other, and the fight is going back and forth,” Ward reflected. “You’re in there punching, you’re getting hit. You don’t realize it, the magnitude of it all until you come out of the ring and everyone is telling you about it.”

His humble assessment of what Gatti-Ward I meant to people is admirable. He continued:

“And then they keep talking about it after that. People keep telling you how good it was, and how blown away by it everyone was. Then it kept getting bigger and bigger, and it became what it is. You don’t realize how special and what it all meant until you come out of the ring.”

Among the honors the fight officially received were: RING Magazine’s 2002 ‘Fight of the Year’ and ‘Round of the Year’ and USA Today’s ‘Round of the Year.’ It was also discussed as the ‘Fight of the Century’ ‘Greatest Fight of All Time’ and ‘Greatest Round of All Time’ in every barroom, chat room, and office lunchroom in America.

Would there be a sequel? And could it possibly repeat the first fight?

With the potential payday a Gatti-Ward II fight would mean for everyone involved, especially Micky, the decision was easy.

“There were talks of me getting the title shot now if I wanted it,” Ward said. Kostya Tszyu had also fought on May 18th, defending his belts in Las Vegas, so him and Ward were on the same fight schedule timeline wise had Micky expressed interest in that bout. “But what am I going to do?” “Fight for a title for $400k or fight Gatti again for over $1m?”

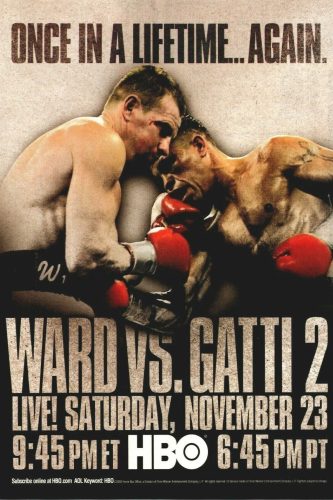

So Gatti-Ward II was booked for November 23rd 2002, six months after the two warriors first encounter. The sequel would fittingly take place at a familiar stomping grounds for both of them: Atlantic City’s Boardwalk Hall.

The $1.2m purse Ward would receive would be the highest ever for a fighter with ten plus losses in their career. No fighter with double digits losses had even come close to $1m before.

The fight was sold out before the ink was dry on the contracts. For the first time since the 1980s, Atlantic City’s flagship arena was packed to capacity on ‘Fight Night.’ And the reason was simple. Gatti-Ward II promised boxing fans the honesty of throwback fighters in a throwback fight.

WHEN the bell sounded getting one of the most anticipated sequels in recent memory under way, it was clear what both men were looking to establish: Gatti was looking to box more than in the first fight; Ward was looking to get inside and make it a brawl again.

For all intents and purposes though, the trajectory of the fight -and history- altered less than one minute into the third round.

With 2:17 left in that round, Ward, looking to step forward, was tagged by a short right.

Because he was coming forward when Gatti threw, the full extension glazed off of Ward’s face, over his shoulder, and slid up directly behind his left ear.

“He got me right on this little bone,” explained Ward, leaning in and folding the back of his ear forward to show me the exact spot.

The punch thrusted Ward’s equilibrium into another stratosphere. He fell to the canvas, but although badly hurt, was able to immediately rise.

Waving off a standing eight count, Ward pounded his chest, and convinced referee Earl Morton to allow the fight to continue.

“The craziest thing happened next,” Ward revealed. “I’m dizzy, wobbly and now I have Arturo Gatti coming after me. He’s battering me, hitting me and then nails me with a double jab and a right hand that caught me square on the button. When that right hand snapped my head back, it actually woke me back up. My legs were still wobbly, but my mind was back. I wasn’t dazed anymore. Every time I went to move for the rest of the fight my legs were shaky, but my mind was fine.”

Ward did still move forward throughout the rest of the fight, but without the strength and stability in his legs, he couldn’t throw or land punches with the same ferocity he did in the first fight.

He had some moments -courageously rocking Gatti in the fourth, and winning his share of the exchanges when the two went inside the phone booth- but an unbalanced equilibrium when fighting Arturo Gatti is too much to ask any man to overcome.

For the next seven rounds Gatti skillfully picked and chose his spots, scoring the necessary points to win each frame.

Ward kept the fight competitive and entertaining, but when the judges tally of 98-90, 98-91, 98-91 -all for Arturo Gatti were announced, nobody was surprised.

“Micky is the toughest guy that I ever fought in my life,” Gatti said afterwards. “There aren’t many guys like him around. The sport needs people like me and Micky Ward. Me and Micky make the sport look good, and we make other fighters work harder when they see us fight. Micky is unbelievable. He has the heart of a lion. He’s my twin, I think.”

Would there be an appetite for a third fight?

“It’s one and one now,” Gatti reasoned. “So a third one; I wouldn’t mind.”

CHAPTER 10 – Gatti-Ward III

HEADING into the third and final chapter of an epic trilogy, where fans could expect the unexpected and knew that anything could truly happen, there was only one thing that was absolutely certain.

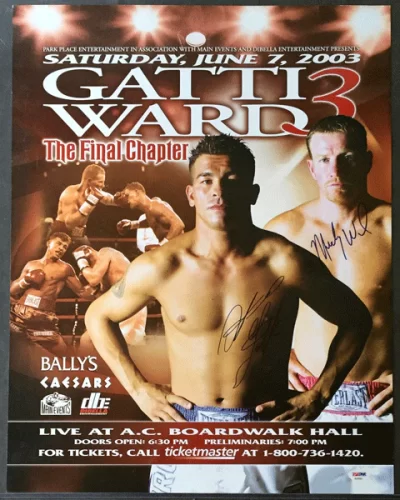

This, unequivocally, was going to be Micky Ward’s last fight. Indeed, it was even being billed by promoters as “The Final Chapter.”

The final installment -and Ward’s final match- would take place right where the last fight did, in Atlantic City’s Boardwalk Hall on June 7th 2003. Only this time, it would be in front of a sold out audience of over 15,000 people, as Atlantic City officials expanded the capacity of the old arena in every manner they could.

The record crowd was then and remains today unprecedented for a non-heavyweight or non-championship bout.

Including his purse for this bout, the trilogy would bring Ward’s earnings to over $3m for the three fights. $3m in a little over twelve months.

DETERMINED to come out more aggressively in his final fight, Ward landed a big right hand in the first round that opened a gash over Gatti’s left eye.

An accidental head butt opened the scar tissue over Ward’s right eye, but Micky is used to addressing that in every fight by now. Gatti’s vision was bothered by his cut and he came inside to better see his rival. This allowed Ward to work to his strength and he stunned Gatti with a sharp hook to the head. It was a great start to the fight and solid first round for Ward.

There was some genuine concern in Gatti’s corner about the severity of his cut. With a sense of urgency he came out in Round 2 bouncing around and pushed the action. Ward was just a step behind, swinging and missing with a few punches. Gatti landed several body shots and an uppercut, and won the round impressively.

“Arturo’s beating him up,” Jim Lampley noted in the HBO booth.

By the end of the third round, Micky was visibly showing the fight on his face. Gatti was boxing beautifully and was up two rounds to one, possibly even 3-0.

“If Micky Ward wants to get back into this fight he is going to need to return to his shock and awe style of fighting,” old friend Larry Merchant observed to the HBO audience.

All you had to do was ask Larry.

Twenty-six seconds into the fourth round Gatti, who had repeatedly flirted with punches at, around, and below Ward’s waistline over the first 23 rounds shot a right-hand that caught Ward’s left hip.

“I knew he broke it right away,” Ward said afterwards. “I saw it on his face.”

Ward attacked. Utilizing a barrage of left hooks and uppercuts that repeatedly found their mark, the momentum began to shift.

Lampley on HBO: “Ward’s back in it now, back in it in a big way!”

In the final thirty seconds Ward punctuated the round by wobbling Gatti with a big overhand right.

In the fifth, Gatti once again showed his incredible recovery and resiliency, adeptly boxing and keeping Ward at bay. He even started sporadically engaging the broken right hand, which had gone numb alleviating some of the pain. The two rivals stood toe-to-toe in the final fifteen seconds of the round firing missels at each other. The fight was beginning to look more like the slugfest of their first, and Boardwalk Hall was roaring with appreciation.

Ward needed to respond again in the sixth, and did.

The round was relatively tame by Gatti-Ward standards, but in its waning seconds Micky countered a Gatti left hook with a straight right to the top of Arturu’s head dropping him for the second time in their trilogy. Gatti received a standing eight count from referee Earl Morton as the round ended, and reassured he was good to go.

“When I knocked him down with the overhand right to end the sixth,” Ward said. “I knew he would still be hurt a little bit at the start of the seventh. My plan was to come right at him as soon as the bell rang. But when I got up off that stool, it was as if I was the one that had just been knocked down. I had no fight, I had no legs, my arms were heavy, I had nothing. I just.. I got old. In that one moment, I got old. I honestly don’t know how I made it through the next four rounds.”

Still, Ward, as he had done in fifty bouts before this one, and for thirty seven years of his life pushed forward and kept fighting.

A short left, right hand combo sent Gatti reeling to the ropes.

“He hurt Gatti with the right hand, hurt him badly!” HBO’s Lampley exclaimed.

It was another back-and-forth round, with the two warriors taking turns brutally assaulting each other.

“I never thought I would ever see something again as exciting as their first fight,” Emmanuel Steward said on HBO as he stood and applauded with everyone else in the arena. “This is equaling it, possibly even surpassing it.”

At some point during that round -or perhaps just the collective accumulation of 27 rounds now standing in front of Arturo Gatti- Ward’s unbalanced equilibrium returned.

“I can’t see him,” he told his brother Dickie. “I don’t know where he is. I see three of him.”

“Hit the one in the middle!” Dickie shouted as stuffed his brother’s mouthpiece back in.

By the eighth round, both warriors were wounded animals. Gatti, with his insane ability to recover between rounds, came out dancing and bouncing to start the round. Ward, swung at the one in the middle, and landed two big rights.

“It’s like they’re not human,” a completely bewildered Larry Merchant, who six years earlier had openly mocked Ward’s toughness and heart, said.

But it is because they ARE human, that made this so special. It is because they are human an entire world became endeared to these two men.

“And then he hit me again on the top of my head,” Ward said. “I was out of it. My brain completely shifted in my head. I had to get double eye surgery because of it.”

Yet, he refused to go down.

With nothing left but instincts -and a warrior’s heart- Ward hunted Gatti down the entire ninth, looking to rip one last liver punch in his storied career.

The final three minutes, the final round of Micky Ward’s career, fittingly began with a hug in the center of the ring with Arturo Gatti.

Midway through the final round, Ward stunned Gatti with a hard left hook to the head sending Arturo stumbling back into the ropes. Micky pursued, hammering away. At one point, Arturo’s backside was pushed through the ropes from the force of Ward’s blows. It looked like Gatti could go down. Somehow, as he had so many other times, Gatti escaped danger by uppercutting his way off the ropes.

Then, in the final thirty seconds, the two men stood back in front of each other and concluded the greatest trilogy in the history of boxing by pouring every last ounce of being into one final brawl. With each other. For each other.

“They’re done,” Lampley said capturing the moment on HBO. “What Micky Ward and Arturo Gatti share together, only they know. Only they can touch it. Only they can feel it.”

When Michael Buffer read the judges totals (96-93,96-93,97-92 for Gatti) it was anti-climatic. What Micky Ward and Arturo Gatti meant then and still mean today is so much bigger than a scorecard.

A few hours later, in the trauma room of Atlantic City Regional Medical Center, Micky lay in his bed waiting to have his wounds attended to. All of a sudden, the curtain closing off his section opened up:

“The doctor said to me ‘somebody wants to say hi to you,’” Ward fondly recalled. “It was Arturo. When he saw me the first thing that came out of his mouth was ‘Mick, are you okay?’ Nothing else. That was it. I was like ‘wow, what a guy’. It just changed my whole mind. What a person. He tried to kill me. We were trying to kill each other and the first thing he says, all that is on his mind, was to make sure that I am okay. We became best of friends right at that moment.”

CHAPTER 11 – Retirement – Part II

SIMILAR to their first fight, the final chapter of the Gatti-Ward trilogy instantly received world-wide praise.

When RING Magazine named Gatti-Ward III its 2003 ‘Fight of the Year’ it pronounced a remarkable run that saw Gatti and/or Ward receiving the distinction in five of the last seven years (should have been six of seven if Ward/Green had been properly selected in 1999.)

Promoters, tested the waters and loosely floated a couple of potential big money fights Ward’s way to gauge if there was any type of interest, but Micky stayed true to his word.

“Nope,” he told them. “I’m retired. I’m done.”

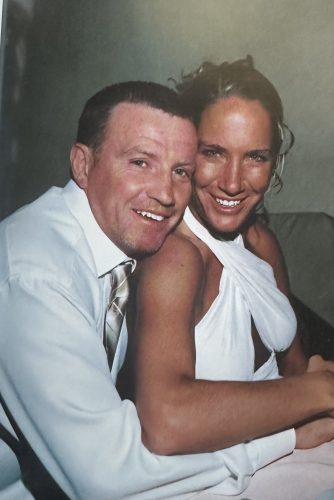

IN 2005, he married the love of his life, long-time girlfriend Charlene Fleming, whom he had been dating since 1999.

At the urging of Micky’s father, George, he went to visit this “beautiful new bartender” at Captain John’s in Lowell. Things started a little slow with Micky and Charlene -similar to how he often needed a couple of rounds in the ring to get going- but once they found their chemistry they developed the wonderful relationship -and marriage- they have today.

“She’s the most beautiful woman I ever laid eyes on,” Ward said. “She’s very good to me. Very good for me.”

WARD may have retired from fighting, but he certainly wasn’t retired from boxing. He would frequently head down to Florida to help old friend Mike Tyson train his fighters.

He also stayed very close to his best friend, his brother Arturo Gatti, with whom he walked to the ring for Gatti’s last seven fights.

“Right before his final fight he called me up,” Ward said smiling. “And in his squeaky Italian voice, he says ‘hey Mick, for my final fight do you wanna train me?’ I said to him ‘are you fucking kidding me, are you serious?’ and then he said ‘what the fuck Mick, do you want to train me or not? I said ‘I thought you were joking of course I’ll train you’ he was like ‘good, you shoulda just said that in the first place!”

IN 2003, Micky ran the Boston Marathon to raise money for the charity Kids in Disability Sports (K.I.D.S.) Moved by the impact he was able to make in helping out the non-profit, he started his own charity to help facilitate similar efforts on a larger and more frequent scale for children in need.

Over the last twenty years, Team Micky Ward Charities has provided financial assistance to children and families in need -to the tune of over $1.2m- to help improve their everyday quality of life.

Be it through his annual golf tournament in June, his motorcycle rally in the fall, various activities such as trivia night in the Lowell school systems, or the K.I.D.S vs Team Micky basketball tournament, Team Micky Ward Charities has been able to help provide excellent opportunities to aid the development of local youth in a fun and educational manner.

CHAPTER 12 – The Fighter

IN 2010, a biopic about Ward’s life, The Fighter, hit the big screen, receiving worldwide critical acclaim.

Just as he had helped secure the big fights -and paydays- later in Micky’s career, Lou DiBella played a valuable role in bringing The Fighter to Hollywood, where Ward was portrayed by Mark Wahlberg, Dickie by Christian Bale, and Amy Adams as Charlene.

The movie was a box office smash, raking in $130m in theatres (on an $11m production budget) and then cleaned up at The Academy Awards with seven nominations.

The Fighter became the first film since Hannah and Her Sisters in 1986 to win both Best Supporting Actor and Best Supporting Actress at the Academy Awards with Bale and Melissa Leo (as Micky’s mom, Alice) receiving the honors.

“Christian Bale plays Dicky better than Dickie,” Ward often says smiling.

It won the ESPY for ‘Best Sports Movie’ and was hailed by Sports Illustrated as the ‘best sports movie since Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro’s Raging Bull.