Cedric Maxwell’s name has been synonymous with Boston’s basketball heritage for more than four decades: a true Celtic legend. But there’s much more to the man than hoop skills and a quick wit.

In the house where I grew up in Southern California, there was a coat closet in the entry hallway near our front door. Around 8:30 p.m. Pacific time on June 11, 1984, my father punched a hole straight through that closet’s door. From the next morning until I moved out of the house during college a few years later, that door was adorned with a vintage concert poster for The Who.

***

One of the men most responsible for this series of events, two-time Boston Celtic NBA champion Cedric Maxwell, bursts into laughter as I tell him the story. Then he says, “Man, that was just the sentiment wrapped around those games — for the fans and especially for the players. That’s why that game (Game 7 of the 1984 NBA Finals, in which Maxwell was the leading scorer in Boston’s title-clinching victory over the Los Angeles Lakers) was so much fun.”

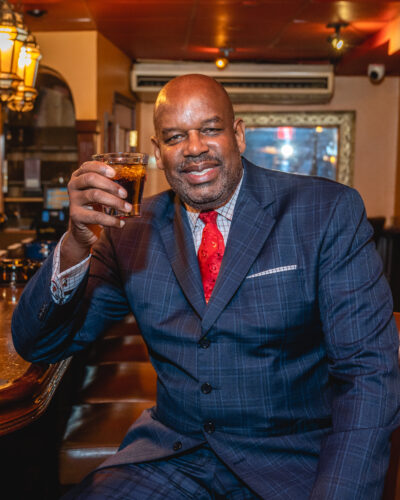

That word — fun — comes up a lot around Maxwell, the legendary Celtic forward and long-time Celtic broadcaster. And while my dad and I would say the real fun happened nearly one year later — on June 9, 1985, when the Lakers topped the Celtics in Game 6 of the Finals in Boston Garden to win the NBA crown — there’s no doubt that when you get to spend time around the man his friends call “Max,” fun and laughs are not in small quantity.

At the same time, when asked to share one thing even his biggest fans might not know about him, Maxwell says, earnestly, “I’m actually very quiet and shy. But I’ve learned to send that alter ego out there, to be the life of the party. What would I rather do? I’d rather come into a room and be a quiet observer. Being 6-foot-8 and 285 pounds, you can’t tiptoe into a room. But, yes, I’m introverted.”

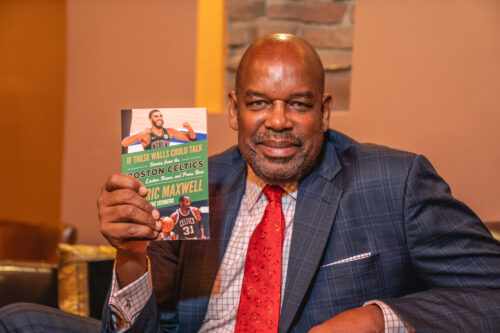

From his upbringing in Kinston, N.C., though, he’s always been an open book. Maxwell’s basketball exploits are well known and his now-quarter-century-long role as a Celtics broadcaster brings him into the homes of millions. In recent years, he’s also found a more personal voice. From The Cedric Maxwell Podcast, co-hosted by Josue Pavon, to his new book — If These Walls Could Talk: Stories From the Boston Celtics Sideline, Locker Room, and Press Box — co-written with Mike Isenberg, Maxwell continues to share incredible stories with the power to make folks both laugh and think.

Across his media exploits, Maxwell makes it easy to feel like you’re chatting with an old pal. Perhaps that’s one reason why — with the recent departure of Danny Ainge from the Celtics’ front office and the passing of the legendary Boston player/coach/broadcaster Tommy Heinsohn — many in New England now see Maxwell as the last of the legends still deeply involved with the franchise.

If that’s the case, it’s not been a straightforward ride to get here, which is what makes Maxwell’s story even more compelling.

From South to North

From his birth on Nov. 21, 1955, Maxwell writes in his new book, “Growing up, I always knew I was loved. My parents, Manny and Bessie Mae, ensured that.” He credits his mother for his “skills on the court” — she played basketball at North Carolina Central, also the alma mater of recently deceased Celtic great Sam Jones.

He grew up with his parents, brother Ronnie, and sister Lisa in segregated Kinston, 30 miles south of Greenville, N.C., and 80 miles southeast of Raleigh. Kinston is also home to fellow NBAers Jerry Stackhouse, Charles Shackleford, Brandon Ingram, and Reggie Bullock. “That’s a lot of players for a town of about 25,000 people. We’ve had a player in the NBA for the last 40-plus years,” Maxwell says.

One thing Maxwell didn’t know about his childhood until recently: the father who raised him, Manny, adopted him when he was four.

“A few years ago, a woman I knew in college told me that she had sent me a letter 40 years ago telling me she had had my child while we were in school at UNC Charlotte,” Maxwell says. “The child had found her, and she’d told this young lady that I was her dad. I met the young lady, and I ended up doing a paternity test, but it came back negative.”

Later, he was sharing this story with his sister, during which he first mentioned he took a paternity test. “Without missing a beat, she said, ‘So you can find out who your real father is?’” Maxwell says. “Awkward!”

It turned out that Manny Maxwell was not his biological father, but rather that a man named Deford Small was, and that Cedric had two more brothers and another sister. Though he never met Small, Maxwell and his daughter Morgan (one of his own four children: two sons and two daughters) visited with those “new” siblings on New Year’s Day 2020 in Greenville, S.C.

“My mother, God bless her soul, and Manny never told me I was adopted,” Maxwell says. “My birth name was Cedric Faulks, my mom’s last name. My father Manny gave me his last name after adopting me.”

With a stable home life provided by his parents, Maxwell played “whichever sport was in season,” but basketball was his calling card, and he accepted a scholarship to UNC Charlotte.

Maxwell made his first national splash as a 49er, leading the 1976 team to the NIT finals (he was MVP of the tournament) and the 1977 team to the NCAA Final Four. In his senior season, he was a first-team All-American, averaging 22 points and 12 rebounds, and was MVP of the Sun Belt Conference, the conference tournament, and the NCAA Mideast Regional. He still holds the school career record with 1,117 rebounds (he also scored more than 1,800 points in his Charlotte career) and was inducted into its Hall of Fame in 2020.

His reward? The Celtics selected him with the 12th pick of the 1977 NBA draft. This had to be a dream come true, right: being selected by a team just one year removed from its most recent championship — which was its 13th in the past two decades?

“I actually hated it,” he says with a laugh. “I’m a Southern boy, you know. No. 13 was Chicago, and I was hoping I’d fall to 14 which was Atlanta. I felt like I’d be more comfortable in a place I’d been before.”

Once the initial shock wore off, Maxwell realized the opportunity in Boston was huge. “Coming to the Celtics, obviously it’s a historic franchise. Then, you think about who the current team had as players and what they’d done, it’s just surreal. When I came in, there were seven All-Stars, and of those, four of them turned out to be Hall of Famers: John Havlicek, Jo Jo White, Dave Cowens, and Dave Bing. The problem was that in 1977, those guys were in their ninth, 10th, 11th, 12th years. Overnight, they got old. That first year, we didn’t make the playoffs.”

But Maxwell did make his mark, both in 1977-78 and 1978-79. As the Celtics’ fortunes flagged (Boston went 61-103 during those two seasons), Maxwell’s stock rose. He averaged a career high 19 points and 9.9 rebounds per game in his second season.

Those Championship Seasons

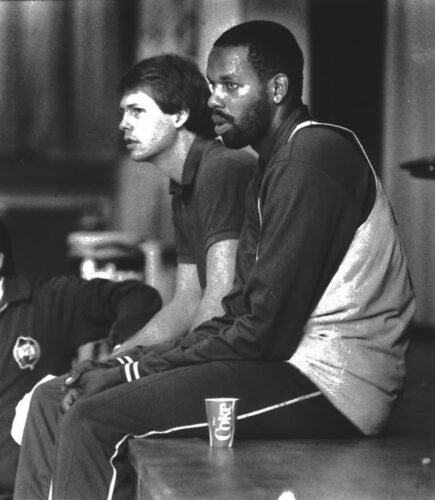

The arrival of Larry Bird and head coach Bill Fitch in 1979 — and center Robert Parish and forward Kevin McHale in 1980 — signaled a return to glory for the franchise. A 61-win season in 1979-80 was cut short in a five-game loss to the Philadelphia 76ers in the Eastern Conference finals. The story would be different the following season.

The Celtics again fell behind Philadelphia three games to one in the conference finals. But in a series that would see five of the seven games decided by either one or two points, Boston rallied behind Maxwell — who famously got into an altercation with a courtside fan during Game 6 in Philadelphia — to gain revenge and reach the championship round against the Houston Rockets.

With that series tied at two, Maxwell put up 28 points and 15 rebounds in a Game 5 blowout in Boston. After a series-clinching Game 6 victory in Houston, Maxwell was named MVP of the finals, averaging 17.7 points and 9.5 rebounds.

Still, though, he calls the Sixers’ series the highlight of the run. “The No. 1 moment was beating Philly. We were down 3-1 to them the year before, and they took care of business. Then we came right back the next year, and it was a proving ground.” Maxwell recalls. “We won Game 5 in Boston, but had to go back to Philadelphia, a place we hadn’t won in two years, just to get it to Game 7. I always tell people this was maybe the greatest series ever played that wasn’t for a championship.”

Last year was the 40th anniversary of that championship run, but — perhaps due to the pandemic — the franchise’s commemoration of it was muted.

“What did they do? Hmm… I don’t really remember anything official,” Maxwell says. “Recently, they brought M.L. Carr and Gerald Henderson out to half court and then introduced me while I was broadcasting the game. But there hasn’t been a bunch of fanfare about it. I think it’s partly because Larry is a little reluctant to come into that building, in that setting. He’s said before, ‘I don’t want to dominate the players who are there.’ To me, it would be so cool to have those guys back.”

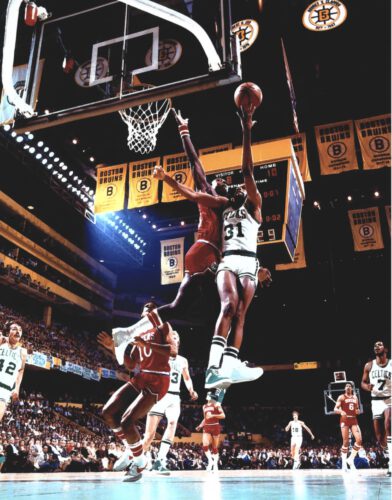

Maxwell’s Finals MVP performance cemented him in Celtics lore, but it was his Game 7 performance against the Lakers three years later that made him a legend.

“It was the series that everybody wanted to see since Larry and Magic (Johnson) got in the league (in 1979),” Maxwell says. He was right. Since Bird and Johnson faced off in the 1979 NCAA championship game (as players for Indiana State and Michigan State, respectively) and then joined the Celtics and Lakers, one of the two franchises made it to the NBA Finals in each season — but they had yet to do so at the same time, until 1984.

“The Lakers dominated early on — your dad was happy,” Maxwell remembers with a smile. “They won the first game. Then James Worthy threw the basketball away in Game 2 to allow us to tie it up. They beat the hell out of us in Game 3 in L.A. They beat us like we broke into their house and were stealing some apples. After the game, I had a car, and I was going to Santa Monica for something. I was listening to an R&B station on the radio, and someone asked the DJ, ‘Have the Lakers won, yet?’ He said, ‘No, not yet, but the fat lady is warming up.’”

Maxwell says the Celtics’ practice for Game 4 was intense. “Guys were throwing each other around, man. We put a rule in there would be no layups, no more Magic laughing. No more ‘Showtime’ passes,” he remembers.

During Game 4, McHale took down Lakers forward Kurt Rambis on a fast break, hitting him across the shoulders and neck and turning the game upside down.

“It was a crazy play,” Maxwell says. “Kevin didn’t mean to do what he did, he just reached out and grabbed him and just happened to hit him high. But that play changed the tenor of the series. We were already fired up. It got the Lakers to be more fired up, but less focused.”

He adds, “My teammate M.L. Carr said, ‘When you got to go home to take a beating, you’re slow to go home.’ Their home was driving and dishing, but when they came to the basket, they were taking a beating.”

The Celtics tied the series with an overtime victory before blowing the Lakers out in Boston in Game 5. “The temperature in Boston that day was 90-something degrees,” Maxwell remembers. “The Lakers swore up and down we turned the air conditioning off. Hell, it was the Boston Garden — we didn’t have air conditioning!”

After the Lakers took Game 6 in L.A. — and Maxwell got into a beef with Lakers’ star forward James Worthy — Game 7 was in Boston. Let’s let Maxwell tell the story:

“On that team, at that time, there was only one guy who’d been a Finals MVP. I knew I had another gear. I was prepared to die on the floor if I had to. I was so pissed off at James. Even right now, he and I still have a war of words that goes back and forth between us when the Lakers and Celtics play,” Maxwell says. “So, before Game 7 in the locker room, I actually said, ‘You b*tches get on my back. I’m going to carry you.’ In retelling, it became ‘you boys.’ That night I had 24, eight, and eight (points, rebounds, assists). It’s one of the proudest moments in my career as a Celtic, and one of the biggest games in the history of the NBA.”

Maxwell still revels in the outcome of the game and the power of the rivalry. He played a big role in ESPN’s “30 for 30” documentary on the Celtics-Lakers rivalry, which debuted in 2017. “I talked a lot of junk in it,” he says. “The Lakers came in the week after the show first aired, and Jayson Tatum was walking on the floor to warm up. He sees me and starts screaming out, ‘Cornbread! Cornbread!’ I’m like, ‘Man, what’s up!?’ He says, ‘I saw that 30 for 30, man. You were a bad m*****f*****!’”

He’s got story after story from those golden days of the rivalry, each one more amusing than the next. To wit:

“The Olympics that summer were in L.A., and M.L. Carr had a shoe deal with New Balance. So, he went out there as a brand ambassador. He went to Fatburger and ordered a burger. The guy taking orders says, ‘You’re M.L. Carr, right?’ He says, ‘Yea, I’m M.L Carr.’ The guy says, ‘I’m not serving you,’ and had the manager get him the hamburger.”

Or:

“We were playing the Lakers in a regular season game, and there were three guys on the Laker bench who were heckling me. One of them was Larry Spriggs. I’m inbounding the ball next to the Laker bench. The referee’s going to give me the ball, and I say, ‘Hold on a minute.’ Pat Riley (the Lakers’ head coach) is standing beside me. I said, ‘Pat, do me a favor.’ I pointed down to that bench and I said, ‘Put one of those m*****f****** in down there, would you?’ He turns and goes, ‘You, Spriggs, get in the game.’ I score about 10 quick points, and I’m talking to him the whole time. Then he gets taken out, but before he goes out, I tell him, ‘The next time you get a chance to watch a free NBA game, you don’t need to be talking if you ain’t playing.’ I always wanted to thank Pat Riley for that. I couldn’t believe it; it was such a cool thing. I was in my element, talking to one of the great coaches, and he happened to give me my wish.”

From Bitter to Sweet

Maxwell was injured late in the 1985 regular season and struggled to return to the lineup. However, his personality didn’t change. That rubbed some of his teammates and, most importantly, team president Red Auerbach wrong. The rift ended when the Celtics traded him to the Los Angeles Clippers just before the 1985-86 season. He played just three more seasons in the NBA (split between the Clippers and Houston Rockets).

Maxwell says that one of the most important things he had to do as a person in the intervening years was making things right with his teammates. “I apologized, not for being hurt, but for not knowing how to handle it,” he says. “I’m a happy-go-lucky person. What you see is what you get. As long as I’m living and breathing, there’s something positive about it for me. When I got hurt, I was still very positive and fun loving, and I think some of my teammates took it that I didn’t want to play.”

That’s not to say Maxwell wasn’t bothered by how his teammates reacted at the time. “They’d played long enough with me to know I was one of the most competitive people they’d ever been around,” he says. “Basketball, backgammon, cards — I was just so totally competitive. I think they overlooked that. Maybe it was my shortcoming not knowing how to proceed forward with that injury, since I’d never had one in my career. Some of the things they said at that time, Red included, were hurtful. At the time I got traded, I wished the Celtics nothing but the best. It was a great run.”

Maxwell remained estranged from the franchise for the first few years of his retirement — “I told myself I wasn’t coming back to Boston,” Maxwell says — until he was invited to Bird’s number retirement ceremony.

“Jan Volk, who was the general manager at the time, persuaded me to come back for that night, and I got such a great ovation,” he says. “They were talking to Robert Parish, to Bill Fitch, to Nate Archibald, and then they came to me. Bob Costas, who was hosting it, said, ’Max, how is it to be back in the Garden?’ All this emotion came, the fans stood up and gave me an ovation. All my teammates clapped. It was such a surreal moment. That kind of opened the door.”

Two years later, during Boston Garden’s final season, Maxwell again appeared. “Each great player who’d played in the Garden appeared on a ticket that season. My game was No. 38 or something,” Maxwell says. “I came back for a nice ceremony. On my way out, Jan said, ‘We’d like to give you a job: we’d like you to come back and do radio. But you need to go apologize to Red.’”

Maxwell’s first reaction: “Apologize? I was the one who got traded.” But, he continues, “Jan says, ‘Max, the father never apologizes to the son.’ So, I ended up going down to Red’s house in D.C. I went in, and he put his arms around me, and he said, ‘When you’re young, sometimes don’t do the smartest things.’ And the next words out of his mouth, I’ll never forget, were, ‘I forgive you.’”

Maxwell adds, “I’m looking at the dude like, ‘What?’ In the back of my mind, I’m thinking, ‘Say something!’ But I stopped and just said, ‘Okay,’ and the rest is history. I’ve been back with the Celtics now for 26 years, doing radio, television, and community affairs. But, man, that’s Don Corleone to the 10th degree right there. You go down to D.C., you kiss the ring. Once you kiss the ring, we can give you a job.”

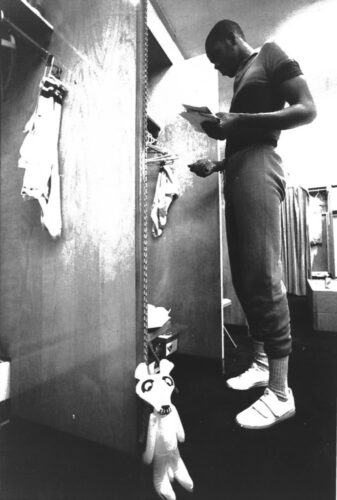

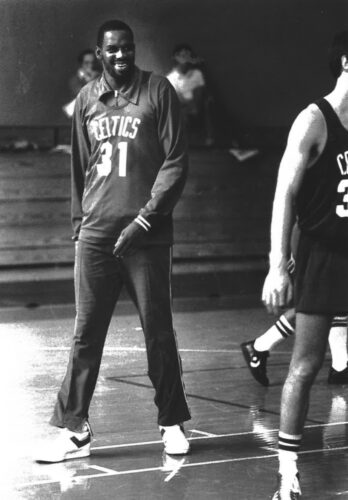

The circle was closed in 2003 when the Celtics gave Maxwell the team’s ultimate honor by retiring his No. 31. “It was a great moment for myself and my family — except for my brother who was there,” Maxwell says. “I thanked my mother, father, my sister — and then someone in the crowd shouted something. It was my fraternity brothers in the top deck, so I gave them a shoutout, and then forgot my brother, Ronnie. At the end, I said, ‘I know I’m going to forget somebody, but thank you to everyone who loves me — and I love you back.’”

Maxwell is now in the midst of a relationship with the city that spans nearly five decades. And he’s not afraid to tell you what he thinks of Boston’s image as a sports town in national media and fan circles.

“People want to talk about Boston as a racist, biased city,” Maxwell says. “For me as an athlete, I’ve never experienced that. I’m in a cocoon, so maybe I won’t. I’m not naïve to think Boston doesn’t have racial issues. But I don’t think Boston is lapping — or even leading — the pack when it comes to cities that have dealt with racial overtones.”

He then points to the history of the Celtic franchise as one of the boldest and most inclusive in the NBA. “Red Auerbach drafted the first black player into the NBA: Chuck Cooper,” Maxwell says. “He had the first black coach, Bill Russell. And he started five black men during a time that the NBA was completely against that. The climate around the Celtics, race was the last thing you saw.”

He then speaks about his own era as a player. “It’s almost offensive when you think of the great players who played on that team,” Maxwell says. “But because you had Larry Bird, because you had Kevin McHale, and because you had Danny Ainge, people viewed that team as a white team. And it was far from that, with the kind of guys we had: me, Robert Parish, Nate Archibald, M.L. Carr, Dennis Johnson — you can go down the line. But when it came to black and white, most people of color were not rooting for the Celtics. They were rooting against the Celtics because of what they perceived as a white team vs. a black team in the Lakers.”

The Boston Brotherhood

It’s quite a twist to see someone who was sent packing to the league’s worst team — with a bad taste in everyone’s mouth about it — return to such prominence with a franchise whose history is written all over the NBA’s 75th anniversary celebration this season.

What kind of relationships does Maxwell have with the other living Celtic legends? “Well, you talk about the main guy of them all, Bill Russell,” Maxwell says. “Whenever I see him, he’s always comical with me. I’ll say, ‘What’s up big guy?!’ And the first thing he does is just give me the finger — with a big smile. It’s a sign of approval. I always tell him, ‘A damn handshake would be fine with me!’”

Jo Jo White is one of his closest relationships. “His birthday is a week before mine — on Nov. 14 — and he’s 10 years my senior,” he says. “When I came in, he was in his tenth year, a fashion icon, a guy I looked at as one of the sharpest dressers around. He took me under his wing.”

White’s style was an inspiration to the fashion-conscious Maxwell when he joined the NBA. “Jo Jo was the first fashionable guy I saw in the NBA,” Maxwell says. “The double-breasted suits, the two-tone shoes. It was sharp. He had the cologne, the bags, just cooler than cool.”

Maxwell also mentions his continuing close ties with Parish, Carr, Henderson, and McHale. “The only one that would be a little different and a little bit of a drag would be with Larry,” he says of Bird. “It’s unfortunate. As a broadcaster, I think I’ve made a couple of comments, and sometimes people get offended by them. I said something like, ‘Kevin Garnett is maybe the greatest all-around Celtic ever.’ It’s no slight to Larry. But I think somebody told Larry in a second-hand conversation, and he took offense to it. He said something like, ‘He’ll quit on them like he quit on us.’ That probably hurt me more than anything, having one of my teammates think I quit.”

When asked about being the so-called “last of the old guard,” Maxwell says, “Hey, Satch Sanders is still around. I always joke with Satch — he’s got 10-15 years on me, so I always say he’s the Godfather right now. I’m just the Godfather’s assistant.”

He continues, “On a daily operation, though, I’m seen more than anyone else who’s been involved with the team. It’s cool, the fact you’re looked at like the ‘O.G.’ of the team. I have fun with it. You’ll hear a mother or father saying to their son, ‘Hey, that guy right there: he played with Larry Bird.’ I’ll come back quickly: ‘No, Larry Bird played with me.’”

Maxwell’s even become friendly with a few of his old Laker foes, like Worthy and Michael Cooper. But the player from those mid-80s Laker teams that he’s closest with comes from home state and Boston ties.

“Bob McAdoo is from Greensboro, N.C. I talk to and about him a lot,” Maxwell says. “My first year in the league, I played in his summer league. And Bob played against me: a Greensboro team vs. a Charlotte team. His team never lost, but we beat Bob. We became great friends. We’re talking about a guy who was MVP of the league, and in my second year, he got traded from the Knicks to the Celtics. He was so mad, he refused to get an apartment in Boston. We had two or three months to go in the season. He slept on my couch for almost three months because he didn’t want to get anything in Boston. He was just that mad!”

‘A Fashion Diva’

If you can’t tell by now, Maxwell is indeed an open book — willing and able to talk about nearly any topic, including one that’s close to his heart: fashion. Well known throughout NBA circles as a stellar dresser, Maxwell’s interest goes all the way back to his childhood. “I’ve always liked to dress up, since I was a little boy. My mother would dress me up for Sunday School: white jacket, bow tie. I was a clean little dude. I always liked fashion, but I never had the money for it, especially when I got tall.”

He also had inspiration from his grandfather. “He was a great dresser,” Maxwell says. “I used to love watching him put on his suits and ties. One of the first things I got when I made it to the NBA was a $700 suit from Louie’s, which was a men’s store in Boston. I remember taking my grandfather there and buying him a suit. It was typical John Faulks. He said, ‘I just want to let you know, when I pass away this suit is going with me.’ When he died, that’s what he was buried in.”

Once in the NBA, Maxwell started going to tailors, but couldn’t find one locally that fit his taste and style. “My brother-in-law went to Korea and had a bunch of clothes made over there,” he says. “I found a way to get my own material that I liked from Italy. I took that to Seoul with me and found a tailor, and that’s how my fashion empire started. I’ve been in love ever since.”

Maxwell says that at any given time, he’s rotating around 100 different pairs of shoes and 100 suits. “My biggest thing, though: I probably have about 3,000 ties. I’ve always been a fashion diva,” he adds.

Max’s Media Empire

Maxwell is clear when asked what his favorite part of being a radio and TV commentator.

“Being able to connect with our fanbase, connect with people on radio or TV — and being able to give my opinion and then have to back it up. That’s a really cool thing to do,” he says.

Maxwell’s skill at storytelling was a plus for him when he entered the announcing booth. What he had to work on was timing. “Because I’m from the South, my natural way was to speak more slowly. I almost had to reinvent who I was as a person. To pick up the pace, I had to be more direct,” he says.

The challenge of radio broadcasting was even more powerful. “On the radio, you’re painting a picture with words, and as an analyst, your window of opportunity is a very small one,” Maxwell says. “Practice watching a play and then dissecting that play — you need to be funny, articulate, and insightful — in about a five-second period.”

It’s not easy, and Maxwell has had some missteps in the booth. The most well-known came in 2007, when he was accused of sexism following a comment regarding Violet Palmer, the NBA’s first female official. “I was doing a game in Houston and Violet Palmer was calling the game. We were doing nothing but praising her,” Maxwell recalls. “Tommy Heinsohn, who hated every referee, was doing the TV broadcast. She made a questionable call, and trying to mock Tommy, I said, in my Tommy voice, ‘Ah, go back to the kitchen and make me some bacon and eggs.’”

He continues, “I still regret that line to this day. I would never try to insult her, because I knew how hard it was for her to get her job. I was poking fun at Tommy, but people thought I was poking fun at her.”

Maxwell apologized for the remark on his next broadcast. The experience sticks with him to this day, especially since he entered the podcast game in 2019.

“Nick (Gelso, founder of podcast network CLNS Media) always tells me, ‘Be who you are. Be as candid as you can,’” Maxwell says. “And in today’s world, it’s a hard thing to do — to be candid and not step on anybody’s toes. This platform now in social media, all you have to say is one word, one phrase, and that can change somebody’s opinion about who you are.”

Maxwell’s nature is perfect for podcasting, which makes The Cedric Maxwell Podcast’s success less than surprising.

“My favorite part is that I get great guests and I’m able to talk about different things,” he says. “Brad Stevens (the former Celtic coach and now front-office leader) said, ‘I like Cedric’s podcast because he doesn’t just talk about basketball.’ We might talk about life, basketball, music, what our differences are. One of the questions I’ve always asked is, ‘What’s your sports Mt Rushmore?’”

He says he asked CNN political commentator Bakari Sellers the question once. “And he had some great answers. But then he turned around later and asked Barack Obama my question in an interview! I didn’t get credit for it!” Maxwell says with a laugh.

Maxwell’s media empire continued to grow last year with the release of If These Walls Could Talk.

“Mike Isenberg knew me from when I played in Boston,” Maxwell says of his co-writer. “He went to Brandeis. He came up to me at a game in Detroit and said, ‘You were my favorite player. When I was at Brandeis, I wore No. 31 because of you.’ And then he asked me about writing a book.”

Maxwell had had other offers to write a book, but he’d never been interested. “For whatever reason, he struck a tone and I said okay. For two or three months, Mike would call me just about every other day and we’d talk for hours. He gave me a chance to regurgitate some great stuff I hadn’t thought of in a long time.”

It’s then that Maxwell launches into one last unforgettable tale — one that’s also in the book.

“We were playing an exhibition game in Seattle, and I met up with this woman I knew in town. We got together and are doing what grown folks do, you know. Later on, I told her, ‘You go home and change clothes and I’ll take you out to dinner,’” Maxwell says. “About 15 minutes later, one of my teammates, Eric Fernsten, calls me up and says, ‘Max, I’ve got two tickets for the Rolling Stones at the Kingdome! 100,000 people.’ I wanted to see the spectacle, so I said, ‘Yea, I’ll go with you.’”

That’s where things took a turn. He continues, “I called her and told her I couldn’t take her to dinner, and she went ballistic. She came down to the hotel, she walked in and said, ‘I’m going to kick your a**.’ So, in my haste to get out of there, I left my key in my room, and I walk down the hall to Eric’s room. I told Eric to go downstairs to get a key to my room. As soon as he leaves, she starts cussing me out again. She jumps off the bed, goes over, grabs his Rolling Stones tickets, rips them up, and flushes them down the toilet! The first thing that crossed my mind: I have to tell this guy he can’t go see the Rolling Stones!”

Maxwell adds, “She leaves, but says, ‘I’m not through with you.’ Fernsten comes back, and he goes off. ‘We have to have her arrested. You took my tickets!’ I told him, man, you know I wouldn’t take your tickets. Let’s just go over there, scalp a couple of tickets and I’ll just pay for them. So, I’m exhausted after this emotional barrage. I get a call around 11 that night, and it’s Bill Fitch. He says, ‘Max, are you okay?’ I said, yea I’m fine, what’s wrong. He said, ‘Are you sure? Two minutes ago, this girl called here and she’s saying crazy things about you.’ If social media was around then, it would have been explosive. (The things she was saying) were the furthest thing from the truth, but she was just so asinine. She wanted anything at all to get me in trouble.”

***

This story comes full circle on a cool early December evening in Charlestown, as the self-appointed fashion diva — in one of those tailored suits — is sitting across from me at historic Warren Tavern, eating a burger in the time between the photo shoot for this story at nearby Boston Cigar Club and that evening’s Celtic game at TD Garden. There’s a group of six of us at the table, talking about the story, the current Celtics season, and more.

“Hey, do you think your dad’s around right now?” Maxwell suddenly asks me. I look at my phone and calculate that it might be his mid-afternoon naptime in California. I try him, but no answer. “Let’s make sure to try him again before you go.”

Thirty minutes later, I dial again, and no answer. Just as I’m getting up to go, my phone rings, and it’s my dad calling back. I answer, telling him that I have someone who wants to talk to him, and hand the phone to Maxwell.

“Now why’d you go and put your fist through a closet in front of your son, man?” Maxwell asks with a laugh. My dad, stunned, but realizing quickly who was speaking to him, says, “Well, you might have had something to do with it!”

The table stops and listens as my dad and Max cut it up for five minutes, talking about the rivalry, the 1984 and 1985 Finals, and more. As the conversation nears its close, my dad graciously says, “You know, as time goes by, I look back and it seems like a grudging respect has replaced the hate I had at the time for those Celtics.”

Without skipping a beat, Maxwell answers, “I don’t know, man. I still hate those damn Lakers.”