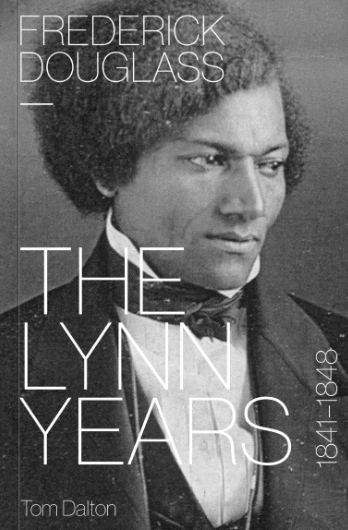

Frederick Douglass is the most renowned orator in American history. In his book, “Frederick Douglass: The Lynn Years” author Tom Dalton takes a deep dive into the eight years Douglass spent on the North Shore.

Most people are aware of who Frederick Douglass is. Douglass’ legacy of self-determination and advancement is widely documented as one of the most remarkable lives in American history.

Douglass, arguably the most prominent leader in the fight to end slavery in 19thcentury America, wrote three autobiographies, established the anit-slavery newspaper The North Starand -with is his fiery and witty tone- became one of the most captivating, inspirational and luminous public orators the world has ever known. He was also appointed to several high level posts in the U.S. government.

What a lot of people do not realize, however, is that Douglass spent eight years from (from 1841-1848) just north of Boston, in the coastal city of Lynn.

These eight years, arguably the most significant of his life in setting the groundwork for Frederick Douglass, the abolitionist, are brilliantly shared in Tom Dalton’s book Frederick Douglass: The Lynn Years.

Below is an excerpt from Chapter Two, “Thief and Robber.”

**

When Frederick Douglass rose to speak on Jan 27, 1842, history was made. It was the first time a fugitive slave had delivered an address at the Massachusetts State House.

For Douglass, it was the largest crowd he had ever faced and his first appearance at an annual meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. On that Thursday night, the State House hall was packed to overflowing.

After Garrison dramatically introduced Douglass as a “thing from the South,” the 23-year old delivered a blistering speech marked by the eloquent oratory, thunderous denunciations and satirical humor that would become trademarks.

“I appear before this immense assembly this evening as a thief and a robber,” he said. “I stole this head, these limbs, this body from my master, and ran off with them.”

At the end of the evening, following speeches by Remond, Kelley, and Phillips, Garrison addressed the enthusiastic audience. He praised Douglass and asked if the crowd considered him a man.

“YES!” they shouted.

Garrison then asked if Douglass was entitled to liberty. “YES!,” came the cry.

“Will you aid the Southern blood-hounds if they should come here after him back to slavery?” Garrison asked.

“NO!” thundered the multitude, in a voice that made the old Hall ring again, a newspaper reported.

Before the two-day event was over, Douglass spoke two more times -at a Friday morning meeting at the Melodeon, a large hall on Washington Street in Boston, and at historic Faneuil Hall, where thousands came to hear the reading of a petition from Ireland asking the Irish in America to join the abolitionists in the fight against slavery.

Five months after stumbling through a halting speech in Nantucket, Douglass delivered one of his masterpieces that night at Faneuil Hall: “The Southern Style of Preaching to Slaves.” He mocked the paternalistic prejudice of Southern preachers, mimicking remarks ministers make while gazing up at the “slaves gallery” in the balcony.

“And you, too, my friends have souls of infinite value -souls that will live through endless happiness or misery in eternity,” Douglass said in biting sarcasm. “Oh, labor diligently to make your calling and election sure. Oh, receive into your souls the words of the Holy Apostle – ‘Servants be obedient unto your masters. Oh, consider the wonderful goodness of God! Look at your hard, horny hands, your strong muscular frames and see how mercifully he has adapted you to the duties you are to fulfill, while to your masters, who have slender frames and long delicate fingers, he has given brilliant intellects, that they may do the thinking, while you do the working.”

The packed hall rocked with laughter and applause.

After hearing Douglass speak at Faneuil Hall, the famous suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton commented: “All other speakers seemed tame after Frederick Douglass.”

As the year went on, Douglass’s notoriety grew. Anti-slavery societies were clamoring for him to speak. A notice for the August annual meeting of the Eastern Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society read: “It would be worth a travel of many miles to the meeting if it were for no other object than to hear Douglass.”

Letters started appearing in The Liberator from people who had attended Douglass rallies. “It has been my fortune to hear a great many anti-slavery lecturers, and many distinguished speakers on other subjects,” one reader wrote, “but it has rarely been my lot to listen to one whose power over me was greater than that of Douglass, and not over me only, but over all who heard him.”

Douglass had a grueling schedule his first full year on the anti-slavery circuit. In April alone, he gave more than 30 speeches in Massachusetts cities and towns. He was on the Cape in the summer and spent from late August through October in New York State with Kelley, Collins, and other agents.

Late in 1842, Douglass and other abolitionists became embroiled in the landmark legal case of George Latimer, a slave from Virginia -and future Lynn resident- who escaped with his pregnant wife only to be captured in Boston by his former master and thrown into the Leverett Street jail. It was one of the first fugitive slave cases to roil Boston.

Both Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, a Marblehead native, and a lower court judge, citing federal law, ruled Latimer could be held until evidence was presented proving his ownership. That drew the wrath of local abolitionists, who formed a Latimer Committee to support the fugitive and even started a newspaper, The Latimer Journal, and North Star. Lynn hosted one of many Latimer meetings, and residents were active in the cause.

“Spirit of Liberty in Lynn,” ran a headline in The Liberator. “Lynn with her characteristic zeal and promptitude, sent no less than seventy good men and women,” to a large meeting at Faneuil Hall, the paper reported.

The first public letter Douglass wrote, which ran in November 1842 in The Liberator was datelined “Lynn,” was on the Latimer case.

“Men, husbands, and fathers of Massachusetts -,” Douglass wrote, “put yourselves in the place of George Lattimer; feel his pain and axiety of mind; give vent to the groans that are breaking through his fever-parched lips, from a heart (im)mersed in the deepest agony and suffering rattle his chains; let his prospects be yours, for the space of a few moments.”

Douglass ended the powerful and eloquent letter with the self-effacement that was a trademark of those early years: “I can’t write to much advantage, having never had a day’s schooling in my life, nor have I ever ventured to give publicity to any of my scribbling before…”

In December, after Latimer’s freedom had been purchased for $400, a celebration was held in Boston presided over by Dr. Henry Bowdich, a salem native and son of renowned mathmetician Nathaniel Bowdich. William Bassett, a prominent Lynn abolitionist, served as president of the meeting. One of the highlights was the late and dramatic arrival of a delegation from Essex County “consisting of hundreds.”

“Then entered Latimer and Douglass, who were received with three cheers,” it was reported.

That year -1842- was also the scene of high drama in Lynn.

In February, members of two lyceums walked out after the organizations rejected proposals to invite Remond, the black agent from Salem and one of the anti-salvery society’s finsest speakers, to address them.

The Lynn members who broke away formed a new organization, The Freeman’s Institute, whose constitution stated that “no person shall be excluded from full participation in any of the operations of this society on account of sex, complexion or religious or political opionions.”

At its first meeting, the group named 23-year old Douglass president pro-tem and 22-year old Lydia Estes secretary. Estes would go on to fame as Lydia Estes Pinkham, who established a wildly successful business selling tonics for women’s ills. She, her mother, and sister had been among the first members of the Lynn Female Anti-Slavery Society.

Lydia Estes wasn’t the only family member to play a prominent role in Douglass’s life that year. Gulielma Estes, an older sister, sparked a scandal in the summer when she walked arm-in-arm with Douglass down Lynn streets. She was confronted by a local Methodist minister, Rev. Jacob Sanborn, who gave her the choice of leaving his church or confessing her wrong-doing. She left.

The Liberator published letters from Lynn residents recounting the incident and the grilling Estes faced from Sanborn.

“Did you take his arm?” Sanborn asked, according to one account.

“I think I did,” Estes replied.

“How far did you walk?”

“As far as Isaiah Chace’s opposite Friends Meeting House,” she replied.

“Did you ever walk with any other colored man?”

“Yes -with Charles Lenox Raymond…”

“Are you much acquainted with colored people?” he said.

“Not so much as I hope to be,” Estes reportedly replied.

During the cross-examination, Estes was asked if she would marry a “colored man.” She replied: “Color would make no difference. I see only character.”

**

Tom Dalton is a former Lynn Historical Society board member and retired reporter for The Daily Item of Lynn and The Salem News who won or shared more than a dozen awards from The National Association of Newspaper Columnists, New England Associated Press, New England Press Association, and others. To order Tom Dalton’s book “Frederick Douglass: The Lynn Years” please go to lulu.com and search by the title.