A hobby almost as old as the pastime itself, the once considered dead art of collecting cards has recently seen explosive growth. At the heart of it in Boston is Costa Cards and its owner, Chris Costa.

In the nascent days of adolescence, before I noticed the curves on girls; before I was too cool to be bothered with anything outside of me, I had baseball cards.

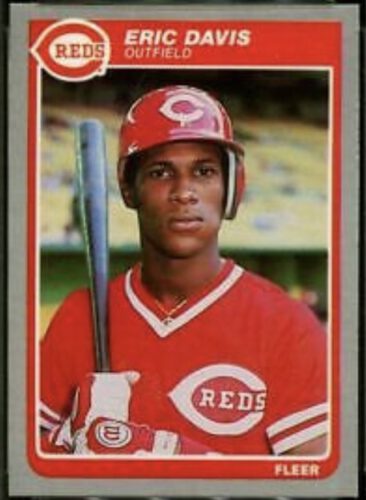

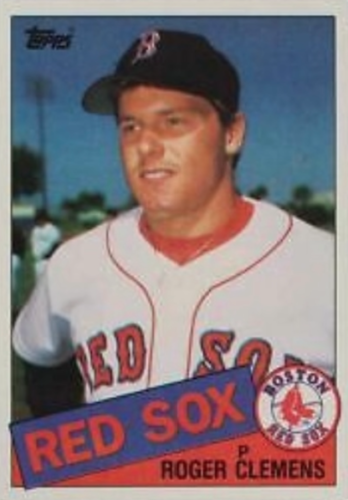

In the late-1980s, before my voice broke, I’d pedal my bike to friends’ houses, a three-ringed binder of my best baseball cards arranged in clear pocket sheet protectors, nine cards per page, arranged in rows of three—with my 1985 Roger Clemens Topps rookie on the front page and concluding with a sheet of Fleer Eric Davis cards—tucked like a football under my arm.

Once I navigated my way through the safe streets of the Rhode Island suburb, I’d fix myself on the carpeted floor of my friend’s bedroom, sodas in front of us, and these clandestine trades would take place.

Then, after years of ardent attention, my penchant for playing cards waned as the desire to get laid grew, and I moved to other obvious things.

I was far from alone.

“I can remember ripping open packs of cards in the backseat of my mother’s car,” said Chris Costa, a sports card dealer also known as Costa Cards on Instagram and a partner in Big Night Breaks based out of Boston. “Then I fell out of it when I went to college.”

Costa attended Bryant University—not far from my hometown of West Warwick, R.I.—where he pitched for the Bulldogs’ baseball team. It wasn’t until he met up with a few old friends from his own hometown of Lynnfield, Mass., and then summer league baseball teammates who never lost their passion for cards that Costa’s own interest was revitalized.

And Costa doubled-down on his old hobby.

Now, following a yearlong global pandemic, where the idleness of quarantine found people restless for sports of any sort, the card industry has experienced an explosion. But pandemic is one of myriad factors, according to Costa.

“The pandemic expedited the snowballing effect in the industry,” said Costa. “But a lot of factors contributed to its growth and explosion.”

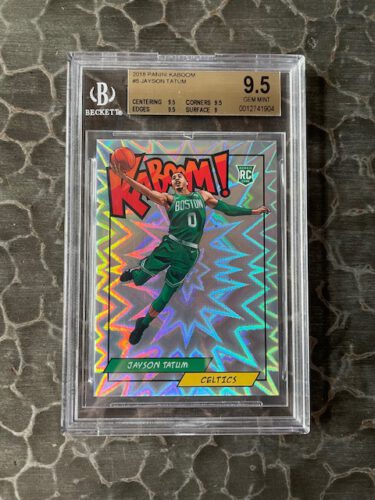

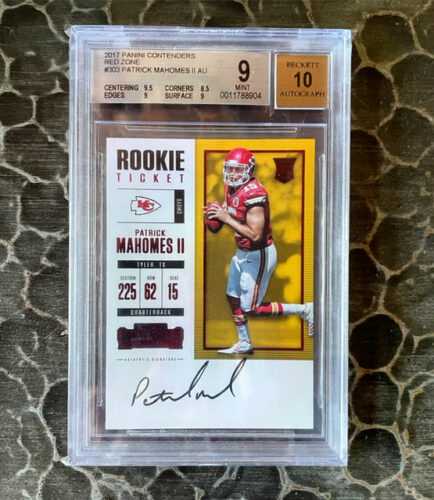

Costa said that there was already “an organic growth” that centered around a lot of young talent in professional sports with rookie cards being a Holy Grail in the business.

He attributes much of its rise to players such as The Celtics’ Jayson Tatum and New Orleans’ Zion Williamson in the NBA; Super Bowl MVP Patrick Mahomes; and a crop of good green talents in the MLB—Ronald Acuna Jr., Juan Soto, Bo Bichette and Fernando Tatis Jr.

This confluence of forces has created an industry that combines on-line commerce and live-stream video with the somewhat archaic art of the handshake deal; it mixes the nostalgic thrill of opening a pack of cards and discovering a ten-fold increase in the original investment with the stomach flutter of watching a Roulette wheel spin and a dealer flip a card in Blackjack; and it’s put one the most defining hobbies of older generations of sports fans in touch with today’s technology.

“It was a perfect marriage for a crazy booming industry,” Costa said.

In short, the trading card industry is back in full-bloom and doesn’t seem to be going anywhere soon.

***

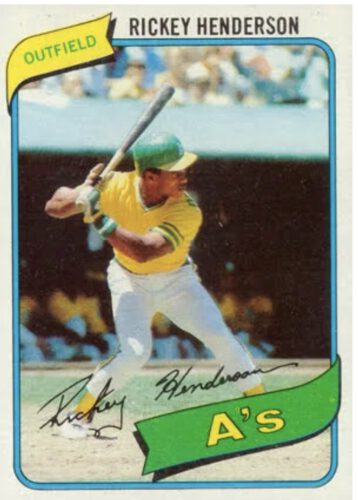

“What do you want for your Rickey Henderson rookie?” Your friend asks.

“I’m not trading it,” you say.

“Come on, the corner is scuffed. It’s barely worth anything anyway.” Then he breaks out The Beckett Guide, looking up what a Rickey Henderson rookie, in “fair” condition is worth. “I’ll give you this Dwight Gooden and a Willie Stargell.”

The wheels spin for a moment as you weigh investments and returns, years before there are real bills to pay. Finally, looking at the 1979 Rickey Henderson rookie card on the second page of your three-ringed binder, you capitulate.

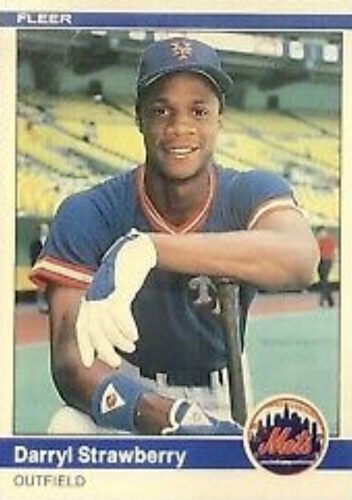

“Okay,” you say. “But throw in the Oil Can Boyd. And that Daryl Strawberry Fleer.”

As soon as the cards leave the sheet protectors and trade hands, you know you were screwed.

***

The baseball card industry is nearly as old and as American as the game is itself. A game that the poet Walt Whitman promised would be “the American game” started to find traction in a populous desperate to heal from the Civil War, in 1868, Peck and Snyder, a New York-based company selling baseball equipment, used this new medium as a means for advertising.

As the game evolved into the 20th Century, baseball cards were issued largely through cigarette companies, who would use the cards of players to secure the product, confectionary companies and The American Caramel Company, who issued many of the first baseball cards.

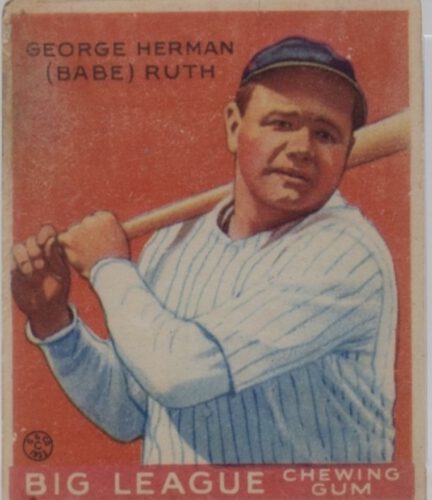

After WWI, however, production slowed until the 1930s when the first cards of players like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig sent production soaring.

Then there was a Great Depression followed by another World War and a period of decline for trading cards.

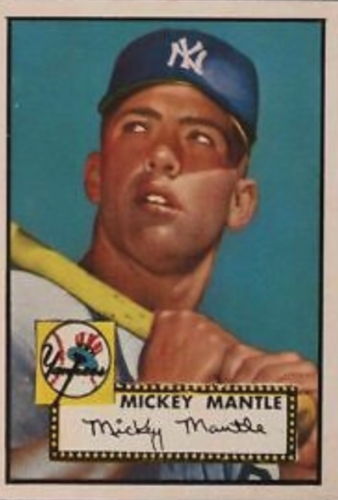

By 1956, the card company Topps took over Bowman, a formidable competitor, and in 1952 printed a Mickey Mantle rookie card that remains one of the most desired to date (Bowman, however, issued a 1951 Mantle rookie).

In 1959, Fleer emerged and would later sue Topps for establishing a monopoly in 1975. By the 1980s, Topps was competing with Fleer and Donruss, and trading cards had expanded well beyond baseball.

Now, some cards claim small fortunes.

For example, the aforementioned 1952 Mantle rookie went for $5.2 million at an auction. A 2013 Giannis Antetokounmpo rookie recently went for $1.81 million, and a 1979 Wayne Gretzky rookie garnished a cool $1.29 million.

The market’s trajectory continues to point skyward, said Costa.

“There’s now a ground swell of popularity,” he said. “There are a lot of real investors, celebrities and public figures flipping cards, and [Big Night Breaks] is trying to make sure the average investor doesn’t get priced out.”

***

It’s Thursday night at The Big Night Group headquarters in downtown Boston, and Costa is in a backroom built for breaks, surrounded by a Scarface-like supply of product—in this case, boxes of sports cards. There’s a “break room” happening in real time on a live-stream as the camera zooms in on Costa’s hands opening the packs. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the people in audience are masked and socially distanced, not nearly as robust as if the room were at full capacity.

Meanwhile, 150 online participants, joining through the Big Night Breaks website and Instagram links, which occurs every Monday, Wednesday and Thursday—with plans to expand—wait as the host Costa opens packs of cards.

The “breaks”—a.k.a. “break rooms”—function somewhat like a casino mixed with hedge fund investors. Every participant in a “break” has invested, either personally or in a group, in the boxes of trading cards purchased by Big Night Breaks, which will soon be unveiled.

Costa said this is something that can alternately scratch a gambling itch, perhaps explaining its allure during the dearth of sports in quarantine. While Costa added that there are multiple formats for “group breaks,” there are still monetary risks involved for investors.

He said that roughly one-third of the investors see a profit while a one-third break even and another third incurs a loss, like any other thrill event where money is waged.

However, there remains a real risk of corporate speculative investors pricing out the average card fan by substantially increasing demand for a product that has an historically consistent supply.

“It’s factors like these that are causing big shifts, and it’s up to folks like us to make sure there is still a way for true collectors to remain active in the hobby,” Costa said, acknowledging that investment firms can flip trading cards as easily as flipping houses for profit. “But we’re trying to find ways to keep the average investors involved.”

But the idea behind the “breaks” is to provide an entertaining experience that mixes “fun, entertainment, excitement and collecting all into one,” said Costa, who opens the packs of cards for those watching on the Big Night Breaks live-stream.

“We just want to create an entertaining experience,” said Costa, who initiated Big Night Breaks with a longtime friend who happened to run Big Night Entertainment Group, one of New England’s largest entertainment groups, in August of 2020 to launch the venture.

Costa also hosted the Causeway Card Show on April 18 and said that Big Night Breaks will soon be opening a card shop—currently unnamed—somewhere prominent in Boston by year’s end.

***

I stored the binder of my best cards that my parents kept in my old bedroom in Rhode Island. I also had shoeboxes full of Topps cards that they gave away, assuming they were worthless.

Most likely, they were. Chris Costa is not going to pull my 1987 Spike Owen Fleer card during a break and experience any rejoicing from his audience.

My parents claim they gave the binder to my son, who showed a brief interest in cards before also turning his attention to the female form. If they gave the three-ring binder to my son, it’s likely gone for good—lost or discarded in the move from our old house to the new one.

But I still remember opening that 1985 Topps pack and seeing a Roger Clemens rookie card—before I knew he was the complete jerk who ended up signing with the Blue Jays and, later, the Yankees (an unforgivable sin).

That thrill in ‘85, was seeing THE pitcher in my hands, who was going to win us the World Series in ‘86, and then lead the Red Sox to many more over the next fifteen years..

I degrees.

Maybe that joy—that quick dopamine hit of fortuitousness—maybe that’s what some call nostalgia. Maybe it’s something we’d all like to get back.

Maybe we all just need a “break.”