‘There’s Just Nothing Like It’

The historic Boston Marathon means so much to so many. For Roseann Sdoia, it’s a lifelong tradition — and a marker for the good things that have followed her life-altering injury in the 2013 bombings.

“I woke up excited. I knew it was going to be a fun day,” says Roseann Sdoia Materia of the morning of April 15, 2013. “It was a crisp spring morning, with a blue, sunny sky. I was in a great mood as we headed into the Sox game.”

Sdoia’s emotional tie to the city’s biggest day — Patriots Day and the Boston Marathon — began when her father started taking her to the annual Red Sox game at Fenway Park before taking a spot along the route to cheer on the runners every year.

On that morning six years ago, Sdoia — a native of Dracut — joined a group of friends that had continued the tradition. “We left the Sox game in the seventh inning to get to our usual spot, outside Forum restaurant near the finish line on Boylston. We had two friends running who we knew were approaching the finish.”

Sdoia echoes many other long-time attendees of the oldest continuously running marathon — the 2019 race on April 15 will be the 123rdedition, dating to 1897 — when she talks about the power of Marathon Monday.

“One of the greatest things about the marathon is to be in the crowd. You’re cheering folks you don’t know,” she says. “It might be a young runner coming through for the first time, or someone in their 80s who’s in the middle of an unbelievable accomplishment. The energy of the crowd supporting them — there’s just nothing like it.”

Devastatingly, that energy was silenced that day, shortly after Sdoia and her friends took their place near the finish line.

“Keep Calm, Breathe Through It”

“The first explosion was down to the left. It was confusing, because I’d been in that environment so many times,” Sdoia says of the infamous 2013 bombings that left three dead and more than 250 injured. “But then someone yelled, ‘Get into the street!’ It was only about 10-12 seconds before the second explosion happened.”

Sdoia ran almost directly into the backpack holding the second improvised explosive device (IED) planted that morning by the Tsarnaev brothers. “There were two flashes of white light, and then I went backwards. I blacked out only for a second,” Sdoia says. “When I came to, I felt like I was laying there forever, trying to figure out what happened.”

Moments later, a Northeastern University student named Shores Salter picked up Sdoia from the sidewalk and moved her into the middle of Boylston. Quickly, Salter was joined by Boston Police officer Shana Cottone. They applied a tourniquet to her right leg, which took the brunt of the explosion. But the scene around them remained hectic.

“There were ambulance sirens coming and going,” Sdoia says. “I was in excruciating pain, but I knew I needed to stay calm so that I didn’t die — keep calm, breathe through it. I was channeling all of my energy into staying alive.”

As Sdoia and her caretakers waited for an ambulance, Boston firefighter Mike Materia joined the group. And when a Boston Police Department van arrived to serve as a makeshift ambulance, Materia grabbed the head of Sdoia’s backboard and helped load her into the van.

“The benches weren’t secure, so the firefighters were holding the backboards on the benches — there were two of us being taken in the van. I remember asking Mike if I was going to die, and his response was, ‘It’s just a flesh wound.’ He was trying to keep me as calm as possible,” Sdoia says.

When the van arrived at Mass General Hospital, Sdoia relented from her drive to stay conscious. “When I saw the van doors open and the light come in from the hospital, I knew that I’d done what I could to stay alive — as had Shores, Shana, and Mike — and the doctors would take care of me from here,” she says.

“We Were All So Thankful”

In the coming days, Sdoia would undergo three progressive amputation surgeries on her right leg under the care of trauma surgeon Dr. David King. She says she could not have been luckier to have King as her attending surgeon.

“As a Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve and surgeon who spent time in Iraq and Afghanistan, he’d dealt extensively with IED injuries, so the moment he walked into the emergency room, he knew what had happened and what to do,” Sdoia says.

King arrived at Mass General after running the marathon himself that day then hearing the news. “He worked for about 48 hours straight. The first impression I had of him was when I woke up from my first surgery, and he explained that I was an amputee,” Sdoia says. “He was kind, soothing, patient. His demeanor helped tremendously with the news he was delivering.”

Sdoia says King is “still just a phone call away,” adding, “He gave me strength to keep moving forward — as with the others who helped.”

One of those others was Salter, the student who’d first moved Sdoia from the sidewalk. But unlike Cottone or Materia, who checked in regularly on Sdoia, she’d lost touch with Salter after she was taken to Mass General.

“As much as he was trying to find me, I was trying to find him,” Sdoia says of trying to locate Salter. “When we finally found each other, he brought his mother along to meet and visit me. She thanked me for saving her son, which might seem odd — but we were all so thankful.”

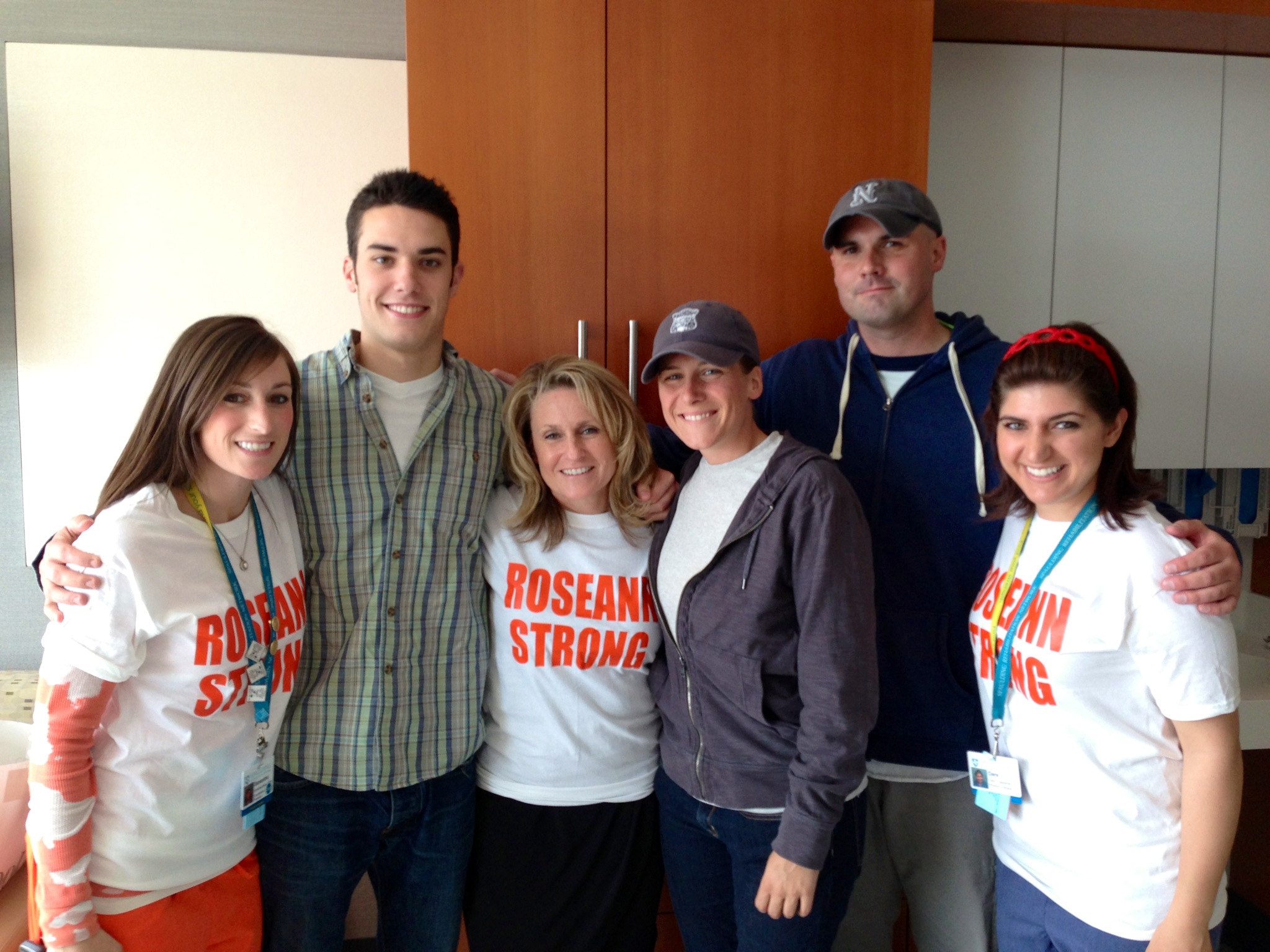

Once Sdoia was out of initial recovery, she was transferred to Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, where she met David Storto, president of Partners Continuing Care and Spaulding Rehabilitation Network, and Dr. David Crandall. “They were very active in working with me, my family, and my friends,” Sdoia says. “They say they were just doing their jobs, but they made investments with their lives to help push me forward.”

Crandall — who also serves the U.S. national amputee hockey team — remembers the day Sdoia arrived. “When she walked in, I told her, ‘I know things about you,’” he says with a laugh. Crandall and Sdoia had a mutual friend — Paul Martin, a member of that hockey team. On Sdoia’s first day, he put Martin on the phone with her “and I didn’t get the phone back for a half-hour.”

But Crandall also says Sdoia deserves most of the credit. “The reality of this is even harder than it looks. She approached this as an athlete might. She was committed to success. When you see that intensity and dedication, you know it’s going to be successful,” he says.

Crandall has his own experience as an athletic competitor — he is a Boston Marathon finisher. And he believes in the emotional power of the event — especially since 2013. “As a marker for what’s good in Boston, that’s the high point,” he says. “Everyone is great to each other, and the event and the day is the very best of Boston.”

“It Was Our Run”

Why do Crandall’s words echo through the comments of nearly anyone who has taken part in Marathon Monday? Why has Sdoia spent a lifetime cheering on the intensity and dedication of the thousands of competitors who run Boston on the third Monday of April? Those who’ve run share the emotional connection.

Chuck Wilkins, 45, of Reston, Va., a 2016 finisher, says, “Growing up as a high school and collegiate distance runner, Boston was — and remains — the measure of a real runner. Not every good runner can go to the Olympics, but every legitimate distance runner has toed the line in Hopkinton.”

Ashlee Lazzari, 35, of Natick, Mass., a 2014 finisher, adds, “Growing up, I always watched the marathon on TV and was in awe watching thousands of runners hit the pavement. I never thought that I could run more than five miles — let alone 26.2 — so the thought of crossing one of the most iconic finish lines was a dream.”

Daniel Pettibone, 45, of Ashburn, Va., didn’t start running marathons until his late 30s, but came from a family of runners. “My dad had run Boston multiple times,” he says. “I qualified in my first try. It was huge for me — and it still is. My first Boston was 2013, and I’ve run the past six races.”

Tiana Rick, 35, of North Andover, Mass., remembers her four Boston Marathons fondly. “The beginning of the race is pure adrenaline. The middle part is when you need to dig deep —your body is tired, but you have a ways to go,” she says. “The last leg is when you rely on the crowd to push you through. There is no comparing Boston to anything else. The crowd, the excitement, the pride — it’s an unbelievable feeling.”

Wilkins agrees, adding that that Boston is about much more than just the runners.

“As we walked to the start line, people were out in their yards cheering for us before the race started. And the way those people looked at us: here was this profound admiration in their eyes, like the way you look at someone when you are in love. They saw something bigger than all of us,” he says. “I saw that same look in people all along the course. I remember running past a Hindu temple early in the race — a crowd of elderly Indians cheering us on. A quarter mile later, we ran past a bar full of rowdy bikers screaming us down the road. In Newton, it felt like running through a mob that parted like the Red Sea. I realized my run wasn’t just my run. It was our run — the runners, the volunteers, the people along the course.”

Pettibone and Lazzari both were part of the fateful 2013 race.

“I was fortunate to have finished and was having a beer in the Westin with a friend of mine from grade school who also ran that day,” Pettibone says. “When the bombs went off, nobody around us knew what happened. We just heard them and felt the building rumble. Then it turned to chaos, and we were essentially trapped there for hours. As we got little pieces of news, the magnitude of what happened really sunk in.”

Lazzari recalls, “One of my friends who helped me train for the marathon had met me at mile 21 to run with me to the finish line. As we approached mile 25, I noticed people were stopped. Someone said that bombs went off at the finish line. I wasn’t running with a phone, but my friend had hers and I called my now-husband Eric, who was waiting for me with friends at the finish line. I called several times and couldn’t get through and realized that cell service had been cut. I went numb, thinking over and over, ‘What if something happened to them?’ Luckily, Eric was tracking me and knew my general location along the route. Somehow, we found each other through the sea of runners and spectators.”

All four have run Boston since 2013.

“After 2013, the marathon became a race that is associated with pride for my city and state,” Rick says. “I don’t know if I would have run it again if 2013 hadn’t happened, but it was extremely important to me to do it for Boston.”

Pettibone adds, “Being there in 2014 and seeing the pride and resilience in everyone has stuck with me. It makes me want to go back every year.”

Lazzari also returned in 2014. “I ran the marathon the following year for so many reasons, but mainly because I wanted to run for those that couldn’t, honor those that were injured that day — and also to finish what I had started,” she says.

“I’ve Worked My Way Into the Crowd”

Speaking of finishing what you start: after Sdoia’s life-changing day in 2013, one person almost never left Sdoia’s side — Materia. He spent a lot of time visiting Sdoia in the hospital. But after Sdoia’s release from Spaulding, things moved to another level.

“He offered to take me to different appointments, so signed him up to come to first prosthetist appointment,” she recalls. “It was great to have two sets of eyes and ears. When I booked the second one, I said, ‘It makes sense for you to come to this one too.’”

They ended up going to four prosthetist appointments. Sdoia says, “Each appointment was two hours. The drives were 30-45 minutes. We’d go to lunch. So, we spent a lot of time together. We got to know each other, found we had things in common, and also found differences that sparked conversation.”

Those conversations turned to romance, and the couple married in 2017, the same year that Sdoia’s book — “Perfect Strangers: Friendship, Strength, and Recovery After Boston’s Worst Day” — debuted (a paperback edition was launched in April).

“The wedding day represented our love for each other and a celebration of life for both of us,” Sdoia says. “We celebrated with family and friends we love.”

Sdoia also has built connections with many of her 16 fellow amputees injured in the bombing. “I can’t imagine life without some of them,” she says. “There’s no guide on how to deal with an amputation, but this group is a huge support system.”

After six months of recovery, Sdoia briefly returned to her career in real estate. “My company, National Development, was amazing,” she says. “But when I went back, my attention still was focused on healing. It was taking away from my work, so I took a step back. They let me go on medical leave for a full year and during that time, I decided to move on. I’d started Robostrong and started speaking publicly about my experience. But my experience as a real estate executive helps me move forward in many ways.”

Sdoia has also moved forward by attending the marathon multiple times since 2013. “I went back the first year — 2014 — for the Spaulding watch party, where I watched from inside, behind a window,” she says. “Since then, I’ve worked my way into the crowd.”

That includes last year, when Materia ran Boston for the Ed Walsh Foundation, which honors a fellow firefighter and close friend who died fighting a nine-alarm fire in 2014.

Sdoia says. “I was amazed by his endurance and drive to push through and finish. Of course, one thing about Mike: he’s a connoisseur of pizza, and at mile 19, a friend met him to give him a couple slices of pepperoni to help fuel him to the finish!”

“As Positive as You Make It”

Sdoia’s recovery from the bombing stands in testament to the #bostonstrong hashtag that’s become a rallying cry for the region. Today, she continues to live her mantra: “Life is only as positive as you make it.”

“We have two choices: either you do, or you don’t,” Sdoia says. “When you wake up, you can make it a good day or make it a bad day. How are you going to deal with the things that happen during a day? You stay positive.”

She adds, “Anytime something bad happens to you, you’re upset in that moment, but each day those feelings lessen and fade — including what happened to me in 2013. It’s not as big or as tragic as it was when it first happened. And since then, so many positive things have happened along the way, thanks to so many people who would’ve never been a part of my life otherwise.”

For information on book signings, motivational speaking engagements & charitable opportunities with Roseann, please contact 617.982.2740 or roseann@robostrong.com. Please also follow on Facebook, Twitter & Instagram: @robostrongsdoia.