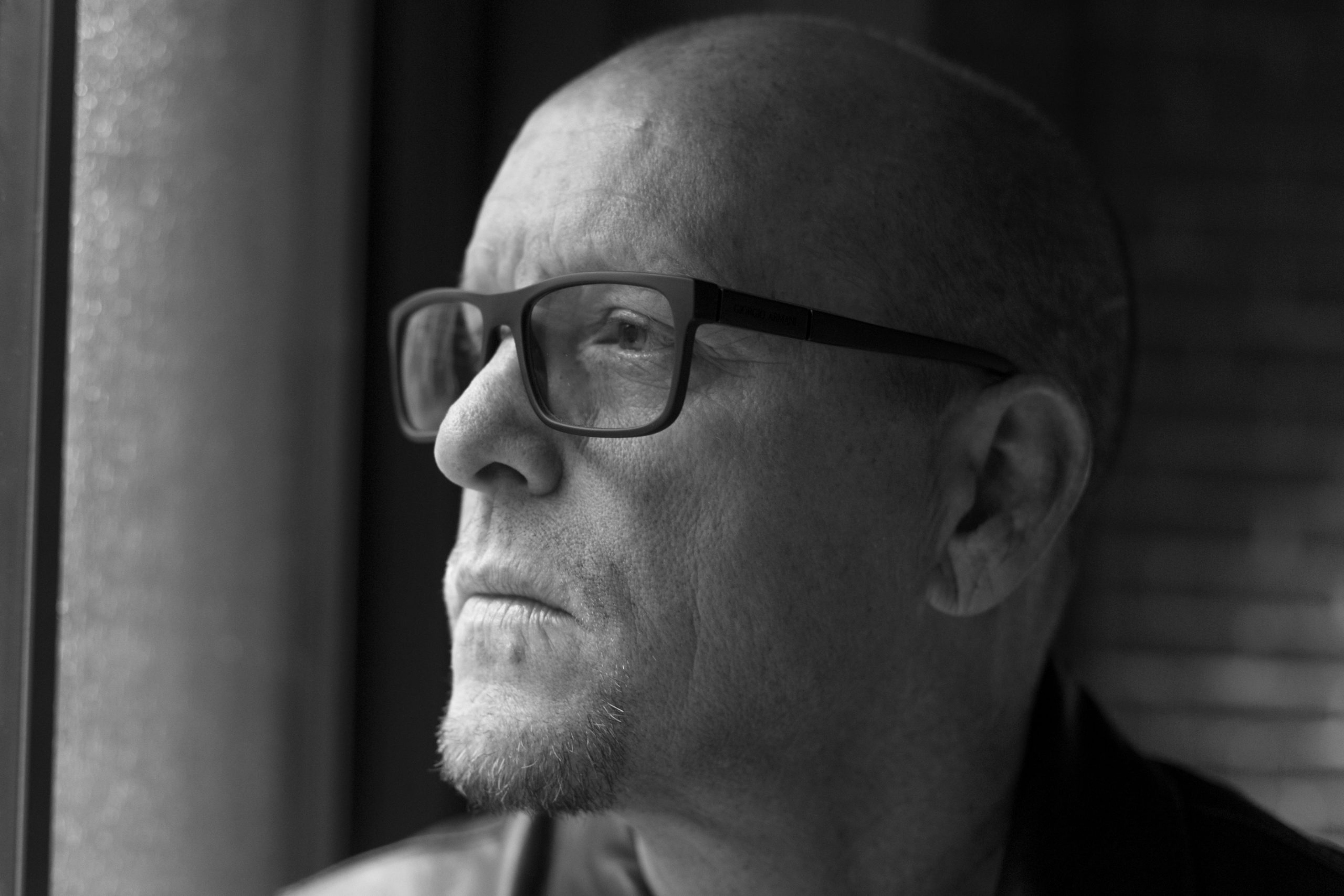

Dorchester Native, Jim Wahlberg Creating Films, Community Dialogue About Opioid Addiction

Jim Wahlberg has a gift to give. He’s accustomed to it by now, as much a compulsion – this giving – as a voluntary act. It’s a necessary part of him after thirty years. Last July, at a crowded theater in Manchester, NH, Wahlberg premiered his latest film, The Circle of Addiction: A Different Kind of Tears, to an assemblage of nearly 300 people – first responders, people in recovery and nearly fifty parents who’ve lost children to overdose. Shot in Manchester on a shoestring budget of $150,000 – a pittance compared to the budgets of his younger brother Mark Wahlberg’s Hollywood blockbusters – Jim’s latest work allows the elder Wahlberg to educate others about the dangers of opioids.

It’s a lesson ripe for the teaching.

Last year, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than 72,000 people – nearly 200 per day – died from overdose, more than triple the number of deaths in 1999. “We’re living in the middle of an absolute epidemic,” Wahlberg said. “To put it in perspective, we lost nearly 20,000 more Americans [to overdose] last year alone than we lost in the entire Vietnam War over twenty years.” In 2017, New Hampshire and Massachusetts had among the highest rates of opioid-related deaths in the country, ranking second and seventh respectively among all fifty states.

“Our mission is to start a conversation between young people and anyone who has influence over young people, so parents, teachers, guidance counselors, clergy,” said Wahlberg who, since 2012, has made six small independent films on the topic of addiction. He notes that parents are quick to teach their children about certain dangers from their earliest years – talking to strangers, wandering off, playing with matches – and feels opioids should be on that short list. “We can’t wait until [kids] figure it out on their own because then it’s too late.”

Wahlberg, 53, knows those perils first-hand. Growing up in a self-described dysfunctional home in Dorchester, the middle of nine kids, Wahlberg started experimenting with pot and alcohol in elementary school. He ran away from home, and, by age 12, he was a ward of the state. By 15, he was a high school drop-out who oscillated between foster care and stints in juvenile detention. At seventeen, he was sentenced to Massachusetts State Prison for armed robbery. Six months after his release, he was arrested for burglarizing a police officer’s home. “He came home, and I was sitting at his kitchen table passed out drunk,” Wahlberg recalled. “I woke up the next day at the police station and had no idea why I was there.” He returned to state prison for nearly three years. “Every crime I ever committed, I was either high and acting crazy, or was trying to get drunk and high, and needed money,” he said.

State prison – and God, he says – saved him. In fact, Wahlberg never intended to find sobriety, nor thought he was worthy of it, in prison. “I wanted to create the illusion that I was trying to get better so that I could get out,” Wahlberg said. “I didn’t think I was going to live a sober life; that was a foreign concept for me.” He found hope and inspiration from other prisoners – many who were trying to get clean – and started to believe that perhaps he, too, could live a different way. “I’ve been blessed,” Wahlberg said. “I was running a game, and, a little bit a time, the game got run on me.” He found sobriety in 1988, having spent much of the decade incarcerated.

Over the past thirty years of sobriety, Wahlberg has worked to give back, a penance of sorts. He has worked in homeless shelters, and detox and treatment centers. He talked constantly to people suffering from addiction or watching their children or spouse suffer. “Addiction does not discriminate, and it will take anybody out,” Wahlberg said. “It’s emotional, it’s painful, but I felt a responsibility to get out there and do all I could [to prevent it].”

But the emergence of new opioids like hydrocodone and oxycodone in the mid-1990s, combined with the elevation of pain management in the medical community as the fifth vital sign of patient care, created a new – if unintended – addiction crisis. From 1999 to 2011, the rate of opioid-related deaths quadrupled, causing the CDC to name opioid prevention one of its top five public health challenges.

That’s because opioids, even when used as prescribed, are highly addictive in that, in addition to relieving pain, they impact receptors in the brain that induce euphoria. The CDC estimates that patients with a one-day supply of opioids have a six percent chance of being on opioids a year later. With a ten-day supply, 1 in 5 patients – or 20 percent – are likely to be using more than a year. “We went from using these drugs for end of life pain management in hospice care to giving them to twelve-year-olds getting their wisdom teeth out,” Wahlberg said. “And they [often] become fully addicted because [these drugs] are extremely addictive.”

And deadly.

Wahlberg estimates he’s met more than 1,000 people who’ve lost loved ones – often their child – to overdose. He says parents would often share stories unrelated to their child’s addiction or death. “These kids were in theater, played music, were athletes, went on mission trips through their church,” Wahlberg said. “Then they made a wrong turn or hung out with the wrong person or went down the wrong road.”

Many parents he’s met want the memory of their children to be about more than their addiction. “They go out every day and fight for other people’s families by showing them where the pitfalls and wrong turns are, and how to watch out for [signs of addiction] so others don’t experience what they have,” Wahlberg said. “These people are heroes.”

He often brings relatives of those lost to addiction with him to viewings of his films – at conferences, schools and community-based organizations. He’s partnered with the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and Walmart to bring his movies about addiction to communities across the country hit hard by opioids. Manchester, NH, for instance, which aired Wahlberg’s 2015 film, If Only, at an 8,000-person Youth Summit on Opioid Awareness in March of 2017, has among the highest overdose-death rates in the state.

Wahlberg is encouraged by communities and policy-makers in places like Manchester, NH that are committed to educating young people and removing the stigma of addiction. He laments that’s not always the case. “In some communities people want to avoid this conversation completely,” Wahlberg said. “They think if they avoid [the community conversation] it won’t penetrate the walls of their home somehow.”

He understands the fear of stigma; he’s felt it’s pain. “If a person has a child with cancer, their neighbors make them meals, cut their grass, go to the grocery store for them,” Wahlberg explained. “But try calling a neighbor and saying ‘my son’s a drug addict’ and see what they do. There is much pain, sorrow and isolation.”

Wahlberg hopes his films – and the dialogue they create – can play a role in reversing the catastrophic impact of opioid abuse. He tells the investors that have bankrolled his films that they will never see a dime in financial returns from their investment, but are going to help thousands of kids learn about the dangers of opioids.

“I did not have any intention [when I started making movies} to immerse myself in this type of service, of using films to reach people,” Wahlberg said. “But if I can help people in whatever capacity, then I can live a good and meaningful life.”

It’s a life Wahlberg could never have imagined for himself, but he knows if he can exorcise the demons of addiction, anyone can. “There’s a line at the end of one of my movies that says, ‘where there’s breath, there’s hope’,” Wahlberg says. “No one is too far down [in addiction] that [recovery] can’t happen for them.”

It’s a message of hope, hard-learned, from Wahlberg, the addict-turned-advocate, who sees his own recovery as a daily gift. “I have learned over the past thirty years that my recovery is contingent upon answering ‘what am I doing today to be the best person I can be?’,” he said. “I can’t keep this gift [of recovery] unless I am willing to give it away.” It’s part of him now — these lessons, this knowledge, these movies – and he hopes that students, educators and parents learn from it as Wahlberg intends: as a gift.

***

MARK WAHLBERG YOUTH FOUNDATION

In May 2001, Mark and Jim Wahlberg, life-long members and advocates of the Boys and Girls Clubs of America, established The Mark Wahlberg Youth Foundation for the purpose of raising and distributing funds to youth service and enrichment programs. Coming from a family of nine children, Mark credits a large part of his success to the fact that he was fortunate enough to spend his free time in the nurturing environment of his local Boys and Girls club. His goal through the foundation is to assist youth to ensure that no child is limited or prevented from attaining their lifetime goal or dream due to nancial circumstances.

Over it’s lifespan, The Mark Wahlberg Youth Foundation has raised and distributed over $10,000,000 to many organizations. Listed below are just a handful of things that the foundation has provi- ded to local youth.

• Their annual summer camp, Camp Northbound, has sent thou- sands of children from Boston inner-city neighborhoods to a week of fun, sports and classic camp events in the pristine outdoor areas in Maine.

• Their annual Christmas Party with Santa has provided thou- sands of gifts to less fortunate children every year.

• They have build basketball courts in the Boston area for the local Boys and Girls Clubs.

• Their dramatic lm, If Only, started a dialogue about opioid abuse for hundreds of thousands of youth and parents across the country.

• They have helped youth in many other ways since 2001. Check out their website at www.markwahlbergyouthfoundation.orgTOGETHER WE CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE.