Publisher’s Note: This spring ESPN’s 10-part series on Michael Jordan and the 90’s Bulls, The Last Dance, captivated the country. Even the most ardent Jordan and NBA fans learned something new surrounding the complex makeup of the greatest basketball player to ever play the game in this candid docu-series.

Jordan, as evidenced through The Last Dance and his dominance, had no parallels.

Or did he?

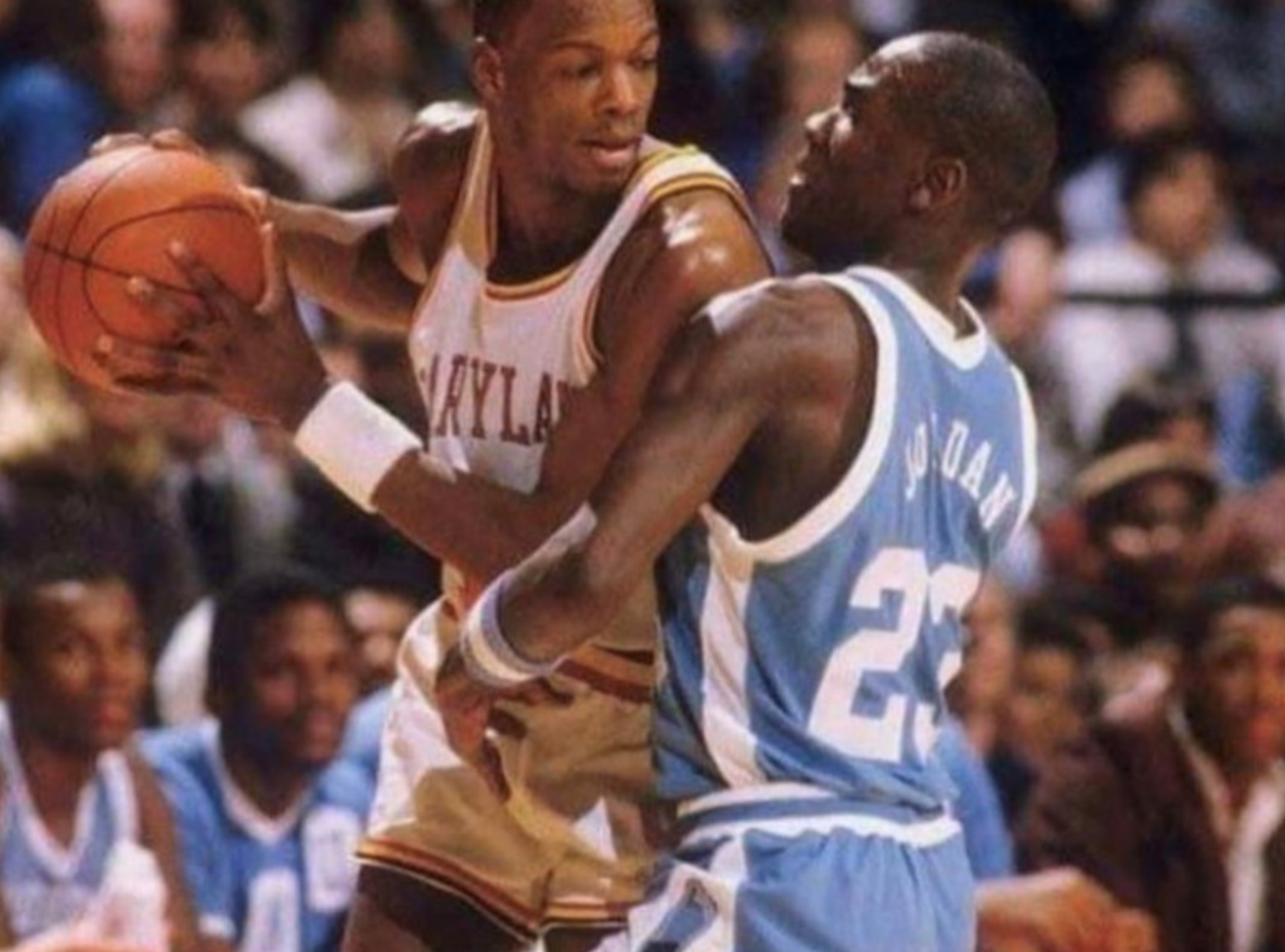

The one person missing from The Last Dance was Len Bias, a mid-80’s rival of Jordan, two time ACC Player of the Year, and the only person Jordan himself ever considered an equal on the basketball court. Jordan’s North Carolina Tar Heels and Bias’ Maryland Terrapins would go to war during the glory days of the ACC with the two best players in the game battling toe-to-toe with each other, bringing out their very best.

So why no mention of Bias in The Last Dance? Sadly, because the pages in his book never got to be finished. Thirty-four years ago today -June 19,1986- the man who was supposed to continue to rival Jordan for basketball supremacy through the 80’s and 90’s tragically overdosed on cocaine, just two days after being selected by the Boston Celtics in the NBA Draft.

As a young boy growing up in Maryland, Lenny Bias was my childhood idol, whom I had the privilege of witnessing magically work his craft on the basketball court on numerous occasions. How good was he? Picture a Lebron James type physique, with Jordan’s athleticism and skills matched with the deadliest turnaround baseline jumper the game has ever seen. That was Bias. Below is an excerpt from Dave Ungrady’s book on Bias, Born Ready, that tells the story not in The Last Dance.

Man, what could have been.

From Chapter 1 – A Mixed Legacy

There are no statues of Len Bias. There is no Len Bias Boulevard stretching across the Columbia Park, Maryland neighborhood where he grew up, a few miles outside of Washington, D.C. There are no memorial tournaments or charity events raising money in his name for victims of cocaine-induced deaths. At least the Columbia Park Civic Association tried to honor Len’s memory. According to John Ware, a longtime neighbor of the Bias family in Columbia Park, the group wanted to establish a $1,000 annual scholarship award in Len’s name for someone in the neighborhood to attend college. But he says Lonise Bias, Len’s mother, turned down the gesture. “She didn’t tell us why,” he says.

But how do you define the legacy of a universally endeared and admired All-America basketball player, one with the potential to be one of the greatest of all time, when he goes and throws it all away? How can you honor a young man whose youthful indiscretion placed the University of Maryland, the school that helped make him a star, into a tailspin that lasted for almost a decade? How can a fan or even a friend of Len Bias salute the vast achievements and joy of his brief life without also acknowledging how his choice that night wreaked havoc on the world around him, both near and far?

You want to, badly. But even 25 years later, you struggle.

Take a leisurely walk through the Comcast Center in College Park, Maryland, the epicenter of University of Maryland athletics and home venue of the men’s and women’s basketball teams, and you will pass a temple of Terrapins tradition and triumph known as the Maryland Walk of Fame. Saunter over to the middle, and you notice two of Maryland’s all-time great basketball players from the early 1970s, All-Americas Len Elmore and Tom McMillen, standing side by side a few feet to the left of a large head shot of Louis “Bosey” Berger, who in 1931 became Maryland’s first basketball All-America. Slide over to the right and, next to the Maryland Terrapins mascot Testudo hoisting a sign that reads “Fear the Turtle,” stands Bias. He is adorned in the glowing gold Maryland jersey with the blazing red number 34, his arms raised triumphantly.

Most of the several dozen Maryland athletes or teams displayed on the wall have been selected to the Maryland Athletic Hall of Fame. Bias is not among them. The only two-time ACC Player of the Year, the All-America is considered by many to be among the top basketball talents ever to wear a Maryland uniform. None of the others left out of the Hall of Fame matches Bias’s athletic impact. Only two Maryland basketball players, John Lucas in 1976 and Joe Smith in 1995, have been drafted higher than Bias in the NBA draft – and to do so, they had to be picked No. 1.

Bias’s number 34 banner was first retired in Cole Field House in 1988, with no ceremony so as to avoid scrutiny. It now hangs from the rafters at Comcast Center, and Bias is recognized as one of the best basketball players in Maryland history. But a Hall of Fame bylaw stands between Bias and membership in the school’s most revered athletic fraternity: Nominees must have good characterand reputation, and not have been a source of embarrassment in any way to the university.

………

In April 2011, Booth talked excitedly about the day he met Bias, his hero. It happened during a promotional appearance by Bias and teammate Keith Gatlin at a sandwich shop in East Baltimore. Booth, an impressionable 10-year-old, arrived three hours early to secure a spot at the front of the line for the 11 a.m. event. When he met Bias, he told him that he would play hard and one day be a Terrapin just like his idol, and, yup, that he would at least tie Bias’s scoring record.

Booth knew the owner of the sub shop and was given close access to Bias and Gatlin once the signing ended. He says the moment is recorded in a picture of Booth with Bias and Gatlin and several others, which hung on a wall in the shop for almost a decade.

When his older sister woke him on the morning of June 19, 1986, after hearing on the news that Bias had died, Booth grew hysterical. He cried uncontrollably as he called his mother at work to tell her the tragic news. Booth was 11 years old. He saw the kinds of people where he grew up in his East Baltimore neighborhood who used drugs. They weren’t like Bias.

Before Bias died, the thought never crossed the boy’s mind that elite athletes used drugs. He used Bias’s death as a reminder to stay focused on basketball and his grades, and to continue a lifestyle that avoided drug use. “Once I understood what it was and how it happened that he died, it made me never want to touch a drug ever or abuse my body,” he says. “It affected my life to help me become the person and man I am today.”

For almost a decade, every time Booth visited the sandwich shop, the photo hanging on the wall reminded him of that happy day. When he was 17, he stopped by one day and it was gone. The owner had moved to Greece, and taken the photo with him. “Every time I tell that story, it makes me sick to my stomach,” Booth says. Bias was gone and now, too, the treasured photo.

Soon after Bias died and long before the photo vanished, Booth went to a sporting-goods store and bought an autographed poster of the player to hang on a wall in his room. There it stayed until his freshman year of college, when he gave it to one of his cousins. “I’d see it every day,” he says. “It reinforced the impact his death has had on me and the player I remember I fell in love with growing up.”

Although he’d seen Bias play only on television, he vividly remembers him as “the first guy who played the game with such passion in college,” sending blocked shots two rows deep into the stands and even slapping the hands of opposing players during pre-game introductions with intimidating force. Those images shaped his career: a Terrapin All-America in 1997, Booth spent 2005 to 2011 as an assistant men’s basketball coach at Maryland. In between, he did something his idol never livedto do: Booth played for two years in the NBA, winning an NBA title with the Chicago Bulls in 1998. But, despite his banner hanging in the rafters of the Comcast Center alongside Bias’s, Booth never did break his scoring record.

From Chapter 2 – Born Ready

Even as his basketball career at Northwestern High School was gaining momentum, Bias had already started developing a fondness for the University of Maryland. While in middle school, Bias had worked in Cole Field House as a popcorn vendor, although Waller insists that Bias spent more time eating popcorn and watching games than actually selling the snack. During the summer, Bias attended Maryland head coach Lefty Driesell’s basketball camps and also spent two summers on the Maryland campus attending Upward Bound programs. Upward Bound provides high-school students achance to take college prep classes and work on a college campus for six weeks.

Then there was the emotional connection. Throughout high school, Bias and Brian Waller would often walk the couple miles from Northwestern to College Park and cruise the Maryland campus, dreaming about the days they would showcase their basketball skills at Cole Field House. Maryland coaches left home game tickets for Waller and Bias. The two relished the experience, sitting nearcourtside behind a basket, watching their hero Ernie Graham along with future NBA players suchas Buck Williams and Albert King lead Maryland to the ACC regular season title in 1980. They dreamed of wearing the Terrapins’ home colors of red, white, black and gold. Dozens of times, they met up on campus with Graham, a Terrapin from 1977 to 1981 who stillholds the school record for most points in a game, with 44. “Everything Ernie did, we did,” saysWaller. “We’d go to his room. We’d go to a gym and play ball. We’d go play in Cole Field House.We were so blessed. We were so happy.”

Waller and Bias played one-on-one games alone on the Cole Field House floor during the offseason,or pick-up games with Graham and other Maryland players. If Graham was in line to playthe next game, he would often do so only if Bias and Waller could play on his team; otherwise, he would wait until the three could play together. The two high schoolers lifted weights in Cole FieldHouse in the same rooms used by Maryland’s basketball players and other athletes.

After workouts, Waller and Bias ate dinner with Graham at a campus dining hall. They accompanied Graham to a party in the campus Student Union and, as Waller emphatically mentioned with a smile, mingled with the college girls. Once, Graham took the two into Maryland’s basketball equipment room and outfitted them with a wide range of Terps basketball gear, including red Nike basketball shoes andNational Invitation Tournament T-shirts. Graham remembers Bias as a nice, enthusiastic kid who smiled and joked around a lot. “He would just show up and stand there at the door,” says Graham. “He wouldn’t want anything or sayanything. He says ‘I’m doing whatever you’re doing.’ He always had that smile, always had a jokeor something funny to say. He kept everybody laughing.”

Graham admits that he started smoking marijuana before he entered Maryland and started using cocaine recreationally while at the school. He says one of his teammates, John Bilney, joked about Graham’s drug use by writing “$100 a gram” on Graham’s door. But Graham insists he never exposed Bias to drugs.“They never used drugs with me,” says Graham, who eventually became addicted to cocaine, an ordeal that lasted until 1994. “The smell of marijuana would be in our dorm room but we would turn the fan on and let it get out of there. But I’m not saying they didn’t smell it on the walls. I would never light a bong or smoke a joint infront of them. I wanted to hide that from them. I wanted them to respect me. I wanted them not to look at drugs.”

…….

Maryland coach Lefty Driesell learned to appreciate a player who had come to him with seemingly limitless but raw potential. The first time Driesell saw Bias play in high school, the player threw the ball at an official and drew a technical foul. “A lot of people told me he’s a hothead, you’re crazy for recruitinghim,” says Driesell. “I knew he was a hothead and a great competitor. I knew he was going to be good. But I didn’t think he was going to be that good.”

Driesell, a devout Christian, was also impressed that Bias became a born-again Christian at Maryland and resumed attending church services. The coach remembers the time he saw Bias sitting alone in Cole Field House reading a Bible. Sue Tyler, a former coach and associate athletic director at Maryland, recalled seeing Bias reading a Bible while leaning against a wall in Cole Field House.Driesell relished Bias’s fun-loving personality and his modest, but passionate, approach to the game.

The coach fondly remembers a typical interaction with Bias when the team would be on the road getting ready to leave a hotel or depart a bus on the way to an arena.

“You ready, Leonard?”

“Coach, I was born ready.”