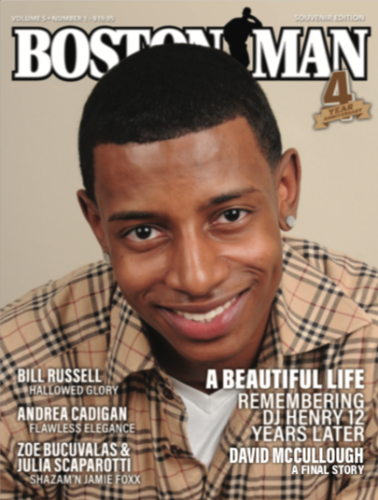

In life, DJ Henry was a natural leader and a compassionate young man of immense character. Twelve years after his tragic killing, his family still fights for justice, while the foundation they started in his name makes dreams possible for children across Massachusetts.

“This isn’t a story. It’s our entire life. We don’t get to shut this off or close Instagram and have it go away. So, when I post things about him, I’m really just speaking from what I know to be true about him. I got the privilege of being his little sister, and I’ll always hold that close.” –Amber Henry

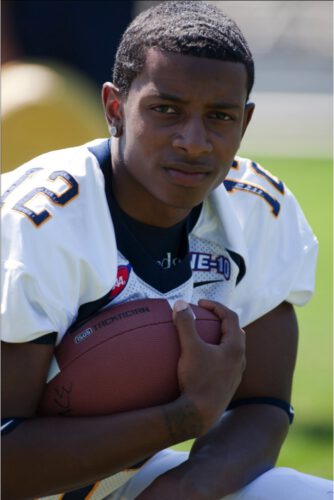

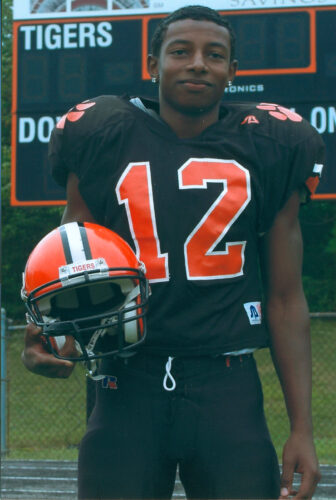

On the final full day of his life 12 years ago — October 16, 2010 — Danroy Henry Jr. wore his Pace University jersey bearing the number 12 for what he did not know was the final time. He and his teammates lost that Saturday’s home contest in Pleasantville, N.Y., against Stonehill College, but there were more important moments at hand.

Not only was Henry’s family in town for his junior season Homecoming game, but also one of his best friends from high school, Brandon Cox, who was a player for Stonehill, and his family. Both families would connect for a postgame dinner.

“We ended up beating them pretty soundly,” Cox told WGBH in 2011. “After the game we all came together, and both our families went out to eat and it was just like being back home, just like high school again. All our families together, having a meal and just enjoying each other’s company.”

Family. Together. Things that still resonate today when speaking with his parents, Angella Henry and Danroy (Dan) Henry Sr. When asked for her favorite personal memory of her son, Angella says, “It’s hard to pick just one. I think the memories us having time together, the five of us, any of those are favorites. Like sharing a meal together: we often said he was a slow eater, because he was enjoying his food. Lots of humming and singing while he was eating because he enjoyed it so much.”

The idea that this meal in Westchester County, N.Y., might be the last the Henry family shared with their oldest son, known to his family as Danny but to the wider world as DJ, could not have crossed anyone’s mind that night. But, just a few hours later, Henry’s parents heard a knock on the door of their Easton, Mass., home and got word from local police that DJ — Danny — had been in “an accident.” A call to a hospital in Westchester County gave Dan and Angella the mindboggling news: Danny is dead.

CHARACTER AND CONNECTION

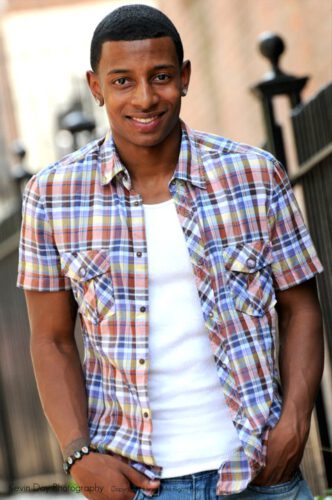

“DJ was a pied piper — for his contemporaries and for kids who looked up to him,” Dan says. “And, we even learned later, for adults. People were drawn to his sense of fairness. He always wanted to make sure he was doing what was right but also what was right was being done. He just cared for people. That’s reflected in his character.”

Born on Oct. 29, 1989, the first of Angella and Dan’s three children (brother Kyle and sister Amber would follow), DJ grew quickly into a precocious child who showed a passion for other people, for learning, and for sports.

“He definitely valued his family, his friends, his faith,” Angella says. “He loved reading about history, and he loved English. Those were probably his two favorite subjects in school. He was really shy: it wasn’t until he was comfortable with you that he could start to have conversations and let his hair down.”

His sister Amber says, “Danny set the tone for me at a very young age. I saw how he spoke to family and friends, and really made that conscious effort to make sure everyone in the room felt whole. I don’t think there’s a specific reason for it — it’s just simply who he is, was, and will continue to be. You don’t meet many people in your lifetime that have a heart like he does. It’s a gift I will cherish forever.”

In an Instagram video shared by Angella, his brother Kyle says, “He was the most nurturing big brother you could ever ask for. The relationship me and him had, it was amazing. He took me everywhere with him … He’s a big man, a big protector, loves his family. He was always so proud to just be around his family.”

DJ excelled at soccer as a youngster, all the way through junior high school. But faced with soccer and football being in the same high school season, he made a choice. “I think football was his favorite sport,” Dan says. “He was really good at soccer and was playing at a high level. He would’ve been able to play in college. But the deal we made with him was when he was a freshman in high school, he could pick. He always wanted to play football, and he picked it when he got to high school.”

That choice to play football at Easton’s Oliver Ames High School led to DJ’s eventual college football career at Pace. During high school, DJ was able to acquire the jersey number that meant so much to him: 12.

“I wore 12 as my high school basketball number,” Dan says. “I think initially he wore the same number as a way to honor me. But then it just became our family number. Anytime any of our kids played sports, that’s the number they chose. Then it went out to cousins and friends — it became a family brand for us.”

Angella adds, “I think we have pictures of him playing soccer in middle school, and he was wearing 12.”

Asked about the tribute to him DJ created, Dan laughs and says, “It certainly wasn’t because of my athletic prowess! DJ and I had a very connected bond through sports, and always have.”

But DJ wasn’t just a stellar athlete and good student. No, he was also doing good deeds, lifting up friends and teammates constantly — often without telling anyone else.

“We heard stories about him giving away cleats and jerseys to people that didn’t have them, and we didn’t know he was doing that,” Angella says. “He was asking us to replace those things, but he was actually giving them to other people that needed them. We didn’t know that. I remember in high school, there was an issue of a classmate being falsely accused of something. He let teachers know that that wasn’t really what happened. He always wanted to make sure there that things were fair. We would hear from his teammates, classmates, even parents when we’d go to football dinners that he was always there to clean up afterwards. He always helped out how he could. He wasn’t always rushing to be the first one at anything. He was happy behind the scenes helping.”

To hear the friends who were with him on the night of Oct. 16, 2010, into the early morning hours of Oct. 17 tell the story, DJ was doing the same, right until the end.

‘TWO HANDS, POINTED AT THE VEHICLE’

After the meal with their families, DJ and his friend Cox went back to DJ’s apartment and played video games with another friend, Desmond Hinds, before heading out on the town with three other friends, eventually ending up at Finnegan’s, a bar and grill popular with locals. Just before 1 a.m., an altercation among other patrons caused the bar’s owner to close for the night. About 30 minutes later, a bartender called local police reporting a “fight breaking out outside right now.”

Though, minutes later, the first arriving a Mount Pleasant, N.Y., police officer — Carl Castagna — reported merely a large crowd on hand but no fighting, the second officer to arrive — Ronald Gagnon — saw a Nissan Altima, the car being driven by DJ, parked in the fire lane. Gagnon said he tried to get the car’s attention by using an air horn, then tapping on the window.

Though DJ had arrived at Finnegan’s with four friends, only he and Cox initially made it back to the car before DJ went back toward the bar to look for his other friends. “As DJ was leaving the bar, he asked one of the owners if it was all right for him to come back in if he needed. Even then, he was trying to follow the rules,” Angella says.

Hinds arrived at the car before DJ returned. The three of them were in the car when Gagnon tapped the window. Cox told WGBH in 2011 that he believed the officer was telling DJ to move the car.

Here’s Cox, again to WGBH: “So DJ put the car into drive and starts to drive away. And as we come around the corner, an officer with his gun raised runs between two police cars that were on the side of us and runs in front of the vehicle with his gun raised and as DJ starts to slow down, he opens fire and then the car speeds back up because there are bullets coming through the front windshield. And I had felt something hit my arm, and I wasn’t sure what it was and look out of the corner of my eye and I can see the police officer on the hood firing into the car from the hood of the car.”

In a story that initially ran in 2018, Hinds shared his memory of the event with CBS News’ James Brown. When DJ drove the car around the corner of the strip mall driveway, “I look, and I see this stance [demonstrates as if holding a gun]. Two hands on something. I didn’t see the gun. Two hands,” he said. “Pointed at the vehicle.”

After the shots, Hinds said, “I didn’t hear anything. It was like everything was silent. But I just saw bullet holes after bullet holes. There was three or four total.”

A bullet had grazed Cox’s arm. But DJ was shot twice — through the lungs and heart.

A Pleasantville police officer named Aaron Hess — 33 at the time — had fired four shots and ended up on the hood of the Altima (Pleasantville is a village in the town of Mount Pleasant). He eventually fell off the vehicle as it came to a stop after hitting another parked police cruiser.

Eyewitnesses on the scene said that Henry was pulled from the car, handcuffed, put face-down on the pavement — and given no medical attention. Police dashcam video shows DJ laying on the ground while Hess sits nearby (he suffered a knee injury). A woman – a civilian – tried to give DJ CPR, but it was 10 minutes before DJ was hooked up to a defibrillator. By then, it was too late.

‘WE’RE FOCUSED ON ABSOLUTE TRUTH’

By the time the Henry family had said their shocking goodbyes to DJ’s body inside a Westchester County Medical Center room, the local police were already sharing their version of events with the media. And that version was directly at odds with what the Henry family was hearing from DJ’s friends in the car.

In fact, in the first 24 hours following DJ’s death, then-Mount Pleasant Police Chief Louis Alagno held two press conferences that would set the tone for all that’s happened since. The official police line was that DJ had accelerated toward Hess, striking him, and propelling him on to the hood, where Hess then opened fire. Alagno also said a second officer, Mount Pleasant’s Ronald Beckley, also had shot at the Altima.

After Alagno spoke out to the media before speaking with DJ’s parents, Dan told CBS News in 2018, “We immediately had a conflict. We clearly knew we needed to get counsel, but I needed a really good local attorney who would push hard to get at — truth.”

The Henrys’ desire for the case has been consistent from the start. “Let’s make sure we’re focused on absolute truth, and when we actually find out what happened — in its truthful form — then let’s let that guide a fair and effective prosecution on the strength of the evidence,” Dan says. “We took a very fact-based approach because we were advised pretty early on about games that would get played. We’d seen it with other people and so we expected it would happen with us.”

Within two days, the Henrys’ attorney — New York civil rights lawyer Michael Sussman — was publicly calling for an investigation into the incident. That call led to a string of students and other bystanders on hand that night, including some who had videotaped part of the event, to begin pushing back on the police’s story. On Oct. 21, Alagno called for a 23-member grand jury to consider evidence of police misconduct in the case.

The very next day, though, a source — likely from inside the police department — leaked information that DJ Henry supposedly had a blood-alcohol content of .13 at the time of the shooting.

“Immediately, we asked, ‘Show us where he was consuming alcohol?’” Dan says.

Angella adds, “The bartender said he hadn’t had a drink.”

The group DJ was with that night said that he’d had one drink before they went out, but as soon as he became the designated driver, he stopped drinking.

Dan continues, “The owner said, ‘He was a nice kid; he wasn’t drunk.’ We have video of him walking around talking to people as they leave the bar. So, it goes back to facts — the absolute truth — where has he been drinking?”

Angella says, “And, you have to remember that the autopsy that was done that they say shows he’d been drinking was done the day before we were told it was going to be done. We had planned to be there.”

Dan says this is just one of “several fabrications in this case.” He adds, “There were several fabrications in this case designed to create a narrative that he was out of control. Play that out: Was he driving recklessly? Evidence bears out that he wasn’t. Hess himself says he jumped on the windshield. The car was nearly stopped, with the brake lights coming on. There’s no evidence, at all, of any recklessness or any impairment. So, again, we ask, ‘Where was he drinking?’”

Both Dan and Angella cite DJ’s character — known by all who knew him — as the clearest defense against repeated attempts by law enforcement — and Hess’ lawyers — to defame him after his death.

“His character was his best defense during those early days when people were casting these false aspersions. His character stood strong against them and defended him,” Dan says.

Angella adds, “His character was definitely his own defense. People would come forward to say, ‘Let me tell you who he was. Let me tell you what he did for me. Let me give you this example so that you can really see a full picture.’ Not just what they were putting out there.”

Two weeks after DJ’s killing, the Westchester County District Attorney’s office reported that the video cameras inside the police cruisers on scene were “not operational” during the shooting. The Henry family then asked a judge to release any video or audio available in the incident but were ruled against. This prompted them to ask the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate.

Throughout the following processes — the local grand jury that cleared Hess of any wrongdoing in February 2011, the federal wrongful death lawsuit against Mount Pleasant for $120 million, and continuing through today, where the Henrys are hopeful that a new investigation by current Westchester County District Attorney Miriam Rocah may finally lead to justice — the Henrys never spoke directly to Hess, but did meet with all three Mount Pleasant police chiefs to have served during this period.

“We were at Hess’ deposition, but didn’t speak with him,” Dan says. “There were three chiefs all in all. We met with all three at different times. When we first met Alagno, he was with his lieutenant Brian Fanelli.”

Fanelli eventually replaced Alagno as chief before being charged in 2014 and pleading guilty in 2015 in a child pornography case.

Throughout it all, the story the Henrys tell makes clear that the only thing local authorities did consistently in the supposed investigation of their son’s death was act inconsistently.

“We were at a bunch of depositions, and they were all different,” Dan says. “Hess admitted he felt guilty, and then tried to clean it up, when he was being deposed. He cried several times and wouldn’t make eye contact with us even though we didn’t break ours with him. Chief Alagno came to us and apologized twice — privately. We told him, ‘You have to do it publicly. What you guys did to disparage DJ was public.’ After he admitted that it was done largely to manipulate the impression of DJ, that it was a false narrative to shift public opinion, he apologized twice privately. But did he do it publicly? No. That’s partly why we forced Mt. Pleasant to apologize publicly as part of our settlement. That was intentional.”

The proverbial fly in the ointment for the authorities in Westchester County, though, turned out to be the man who was named as the second officer to discharge his firearm that night: Beckley.

On Oct. 2, 2012, in a deposition in the Henrys’ federal lawsuit, Beckley testified that he had fired at Hess, who he believed to be the aggressor in the situation and didn’t realize he was a fellow officer. It was the first time in a 30-year career that Beckley had fired his weapon. “I was shooting at a person that I thought was the aggressor and was inflicting deadly physical force on another,” Beckley said in his deposition.

“Ronald Beckley was very remorseful,” Dan says. “He wished they could’ve done more to save our son’s life. He tried. He was sad and broken. He was standing against the same blue wall we were standing against, even though he was a member of law enforcement.”

Dan and Angella say that Beckley’s testimony showed that the police’s coverup of what truly happened began that night when Fanelli took Beckley behind closed doors and then submitted a fabricated statement into the police report.

“Beckley told him exactly what happened. He brought Beckley to Chief Alagno’s office, they told Beckley to get a lawyer, and then submitted a false statement into the evidence, saying that Beckley was shooting at DJ — basically ascribing to him the same sort of statements that they were writing for Hess,” Dan says.

Angella adds that she doesn’t understand why the department rallied so readily around Hess. “It doesn’t make any sense,” she says. “With Hess, one of the things I walked away from this with is the feeling that he was just incompetent for the job.” (Incredibly, the Pleasantville Police Benevolent Association gave Hess an “Officer of the Year Award” shortly after the grand jury made its February 2011 decision not to charge the officer.)

Another target of the Henrys’ ire is former Westchester County district attorney and chief justice of the New York State Court of Appeals Janet DiFiore. She made the initial decision allowing the police department to investigate its own wrongdoing.

“She had political ambitions,” Dan says of DiFiore, who resigned from her role as the top judge in New York State this summer while under an ethics probe. “She didn’t care. She’s on the record with a local councilwoman saying, ‘I’m not going to let this small-town cop ruin my career.’”

He continues, “Janet DiFiore never gave it a chance. She never tried to give it a chance. And I told her as much. She was trying to get this thing out of her purview as quickly as possible, with as little damage to her as possible.”

In 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice declined to bring charges. That was somewhat unsurprising considering the strictures of the law in the case.

“The DOJ did acknowledge that there was some sort of wrongdoing, but they couldn’t fit it into the narrow law,” Angella says.

Dan adds, “They had to show intent — premeditation and intent.”

The Henrys came to settlements with both Mount Pleasant and Pleasantville in 2016 and 2017. But, as Angella says, “It wasn’t really what we wanted. We were kind of bullied into doing that. It happens in a lot of cases unfortunately. You’re kind of pushed into making a decision.”

TAKING ANOTHER LOOK

The Henrys remain steadfast in their desire for justice.

A 2019 public service announcement video from the NFL Players Coalition focused on DJ’s story. Then following the infamous 2020 police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, a group of celebrities including Rihanna and Jay-Z (who’d recorded a song with Kanye West in 2011 called “Murder to Excellence” that name checked DJ) asked then-U.S. Attorney General William Barr to examine DJ’s case.

About 16 months ago, the family received a ray of hope from Rocha, the new district attorney of Westchester County, when she appointed a former federal judge to oversee a review of DJ’s death, as well as the 2011 death of 68-year-old Kenneth Chamberlain of White Plains, N.Y.

“She was willing to reopen it and to take a look. She was willing to do that with both DJ and Ken Chamberlain Sr. We’re waiting on her recommendations on that,” Dan says.

Angella adds, “She hired an outside firm that’s doing the investigative work.”

Dan continues, “What is still within the statute of limitations? That’s what we’re going to find out. This is reopening the criminal process, so we’ll take her lead.”

Did the more recent national exposure of DJ’s case help create this progress?

“That’s a great question for D.A. Rocha,” Dan says. “She ran as a progressive and won this seat in Westchester County. And I think our impression is that she’s honoring her commitment to become a progressive reformer in lots of ways, and in this case. Having those voices out there saying DJ’s name, that definitely raised awareness. There were a lot of people out there that don’t even know about him. It was shared a lot of times and brought traction back to it. We appreciate Rocha’s courage in wanting to go back in and look at this.”

The Henrys consistently have taken a high road, trying to avoid the political morass that often taints any case that falls into the “black kid/white cop” conversation. Why?

“I’m not sure if we take the high road,” Dan says. “Use of force is an important tool for law enforcement, but it always must be used lawfully. In every one of these cases, the first question that must be asked is, ‘Is that lawful?’ There are all these circumstances that create this narrative, and then people find their place in the polls. Somewhere in the middle of that is a real solution — a real answer to that real question. If it’s unlawful, then there should be some convictions, some accountability for it. If it’s lawful, then it’s the way it’s designed. An effective use of force, lawfully.”

Angella adds, “We made a very clear decision not to make it about race, because then, as you’re saying, you lose sight of the facts and people just focus on that one part. If you make it about race, it just becomes about race and there’s more to it than that.”

Dan continues, “It doesn’t mean it isn’t about race. Rather, it’s how does race play into the fact pattern that makes it either lawful or unlawful.”

They’re also focused on solutions to how the issue of social justice and police misconduct can be fleeting in the news cycle and — therefore — to the average person’s consciousness.

“If people start getting convicted for wrongful shootings or abuse in custody, that will start to set it back on the right cycle, more than anything else,” Dan says. “If it’s lawful, then fine. If it’s unlawful, then you should get treated like anyone else who commits a crime against another human being.”

Angella then adds important context to anyone familiar with how cases like this have played out. “You have to define lawful, because right now they’re able to say, ‘I was in fear for my life,’ and that becomes lawful,” she says.

Both Henrys are clear — and have been for 12 years now — that they are not interested in the political arguments the death of their son engenders. Their only interest is justice. What would that look like for each of them?

“On the micro-level, for me, Hess would be in jail,” Dan says. “Fanelli would be charged, at a minimum, adding to his felonious record — some obstruction charge, some tampering charge, and would be prosecuted for his actions. And Beckley would have whatever pensions are due him restored. And he’d find his place of honor, rightly so, for doing the all the right things.” (When he retired, three months after DJ’s death, Beckley was denied a full disability pension.)

Angella says, “At the end of the day, none of this is bringing our son back. But there needs to be some accountability somewhere. For our family — for Amber, for Kyle — that would give us a feeling like there is some justice in this world. It’s really hard to know that the person that killed your son is out living his life as though nothing has happened.”

FUNDING KIDS’ DREAMS

Four months after DJ’s death, the Henry family established the DJ Henry Dream Fund — initially covered in BostonMan in summer 2021.

The fund provides community-based scholarships to Massachusetts children between the ages of five and 18. It provides financial support allowing youths to participate in community-based programs such as sports, performing arts, and summer programs. The non-profit’s website says, “Participation in such programs, despite economic position, empowers young people to be the best they can be.”

“It was Dan’s idea in the weeks after DJ was killed,” Angella says. “We were having many moments of grief, and Dan said, ‘I just really want to do something that will honor him.’ And because he was such a lover of all things sports, we’ll give equipment away. Because that’s what he was doing when he was growing up. We later found out that there was a foundation doing that. So, we decided that we would pay the fees so kids would have the opportunity to play.”

The fund is close to reaching 8,000 children served during its 11 years in existence. “Our kids and your kids are fortunate,” Angella says. “They don’t hear ‘No’ often. There are plenty of children whose parents, grandparents, or guardians can’t afford it. To know that there are so many children being served by the foundation has truly been one of the highlights of all of this. And new children are learning about DJ as a result of the foundation. In the next year or so, we’ll reach $1 million in giving, and that’s a big deal. There are so many children that need and deserve it, and we didn’t even know there was this need when we started it.”

Dan adds, “Of those 8,000 kids, some have been served multiple times. They can apply more than once.”

Though October has generally been a big month of events for the DJ Henry Dream Fund, this year the non-profit’s gala was moved to April. So, this year — 12 years since his loss — in remembrance of DJ’s birthday on Oct. 29, the Henrys chose to do something simpler.

“We’re just asking people to perform an act of kindness, a day of service, do something for others, and we’ll be doing the same. We want to be focused on how he lived, how he served others, so that’s what we’ll be doing,” Angella says.

Dan says others are planning events, as well. “The Black Student Union at Pace University is planning a vigil at both campuses,” he says. “DJ wasn’t there with these kids, so it’s a powerful testimony on his legacy and impact on people who are coming to know him now in their own way.”

Angella mentions that the Hockomock League — a high school athletic league that includes DJ’s alma mater, Oliver Ames — is working on having a game dedicated to DJ’s memory in each town in the league. “And his high school has started a four-year curriculum that will be focused on him,” she adds. “The freshmen will watch the ‘48 Hours’ episode from 2018, the sophomores doing something for the Dream Fund, and so on. It’s being worked out now. This will be the second year. There also was a tree planting in the courtyard at his high school with a plaque dedicated to him.”

What’s next for the fund? “Just to try to reach the $1 million mark in funding,” Angella says. “In summer 2021, we did a wonderful comedy night where both Seth Meyers and Amy Schumer donated their time and did a standup for us. It was hugely successful. We’re hoping to do something again like that next year.”

Dan adds, “That comedy night allowed us to stand up programming with the Boys & Girls Clubs of Martha’s Vineyard for island kids who don’t have much to do over the winter.”

All of this is a wonderful way to honor DJ’s memory. But having only memories remains painful. How can others honor him and carry forward who he was for future generations to understand?

His sister Amber says, “One way I honor him is to make sure that every single person in a room knows they are meant to be there. I want people in a room I’m in to feel the same love he had for each and every person around him.”

In the Instagram video shared by Angella, brother Kyle, who’s become a musician, says, “Our connection with music was huge. It’s basically why I keep going. He always told me, ‘I can’t make music, but you can, so make something, make something, make something.’ … I honestly would be lying if I say I’ve had real healing because I keep seeing this stuff happening every single day … whether or not I get to truly heal or not, I owe it to him to make sure that his legacy Is told in the way that it should be. His truth.”

Dan adds, “Be good to other people. That’s DJ personified: just try to be good to other people.”

And Angella, after a few moments of contemplation, says. “Be compassionate. He was very compassionate.”

We encourage you to also read about DJ Henry Dream Funder Quincy Pickett, one of the many success stories and beneficiaries of the The DJ Henry Dream Fund.

Please also go to BostonMan Magazine publisher Matt Ribaudo’s column, who after spending some time with Desmond Hinds, urges readers to See the Whole Picture.